Lorissa Rinehart in Lapham’s Quarterly:

It was no coincidence that the world’s introduction to industrialized warfare determined the shape of Johan Varendonck’s opus on daydreams. Varendonck himself didn’t expect daydreaming to be the subject of his only book; his studies began in a different field. But World War I—and Freud—intervened. Born in 1879 to a Belgian schoolteacher and his wife, Varendonck hadn’t done much to distinguish himself by the time he turned thirty-five. Following in his father’s footsteps, he took up a career in education, becoming a lecturer at Ghent University, just eleven miles from his hometown of Zelzate. He eventually enrolled in a pedagogical doctoral program in Brussels, but the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s declaration of war on July 28, 1914, interrupted his graduate studies and pursuit of a better life.

Academic ambitions notwithstanding, Varendonck volunteered for armed service the moment Kaiser Wilhelm sent his army marching to France via Belgium. His passable command of English earned him a post as translator for the British Royal Naval Division stationed in Antwerp, where the Allies hoped to stop the German war machine before it got up to speed. The Allied commanders had reason to believe they might succeed. In the past, Antwerp had proved nearly impregnable, ringed by a series of earthen and stone fortresses collectively known as the National Redoubt.

But when the Germans arrived in August 1914, their Big Bertha guns effortlessly vaulted Antwerp’s medieval defenses. Bomb-laden zeppelins sailing far above defenders’ bullets dropped their payload on the city’s center. By September the Allies’ chances looked bleak. Things were not that bad for Varendonck, all things considered. His post kept him far from the front while most of the people he was tasked with translating for were occupied with battle, leaving him time to finish his original pedagogical thesis. By early October Varendonck’s scientific investigation of educational processes in Belgium was ready to send back to his advisers. Unfortunately, Antwerp erupted into chaos before he had a chance to put it in the mail. The city’s defenses collapsed on October 10, 1914. German artillery fell like a hailstorm, igniting oil tanks and apartment buildings until the entire city was one enormous conflagration. Civilians poured onto the docks of the Scheldt River, clamoring to board anything that would float. Hoping to fight another day, the Belgian army hastily retreated west, toward the Yser River.

Amid the pandemonium, the pages of Varendonck’s thesis disappeared.

More here.

Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups.

Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups.

A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of

A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of  That the Latin name for the caper flower, Capparis spinosa, is related to the Italian word capriolare (meaning ‘to jump in the air’), is a droll enough visual/verbal play to suggest that Titian is intentionally teasing us with the placement of the prickly perennial plant directly under the bouncing Bacchus. But it is the plant’s medicinal use, since antiquity, as a natural carminative (or remedy for excessive flatulence) that reveals the artist is truly letting rip with some mischievous fun. In the context of Titian’s carefully deployed caper, Bacchus’s explosive propulsion from his seat appears more wittily, if crudely, choreographed by Titian, who demystifies the lovestruck levitation by providing us with a more down-to-earth explanation for the cheeky lift-off. In Titian’s retelling of Ovid’s myth, Bacchus has been hoisted by his own pungent petard, as Shakespeare, who likewise loved toilet humour, might have said.

That the Latin name for the caper flower, Capparis spinosa, is related to the Italian word capriolare (meaning ‘to jump in the air’), is a droll enough visual/verbal play to suggest that Titian is intentionally teasing us with the placement of the prickly perennial plant directly under the bouncing Bacchus. But it is the plant’s medicinal use, since antiquity, as a natural carminative (or remedy for excessive flatulence) that reveals the artist is truly letting rip with some mischievous fun. In the context of Titian’s carefully deployed caper, Bacchus’s explosive propulsion from his seat appears more wittily, if crudely, choreographed by Titian, who demystifies the lovestruck levitation by providing us with a more down-to-earth explanation for the cheeky lift-off. In Titian’s retelling of Ovid’s myth, Bacchus has been hoisted by his own pungent petard, as Shakespeare, who likewise loved toilet humour, might have said. The original Garden of Emptiness, Kyle Chayka explains in his pugnacious whistlestop tour of minimalism, is to be found in the 16th-century rock garden of the Kyoto Zen temple Ryoan-Ji. Chayka journeys to this sacred spot in search of the philosophical minimalism that has been obscured by today’s commodified decluttering. His book, which ranges from the Stoics and Buddhism to Mies van der Rohe, is a rebuke to the Shintoistic declutterer Marie Kondo, whose bestselling Netflix-powered KonMari method urges us to retain only those possessions that ‘spark joy’ and to practise such techniques as folding trousers vertically and not – heavens! – horizontally. Chayka warms to Donald Judd’s Plexiglas, Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Brian Eno’s ‘Discreet Music’. He is irked by minimalist hipsters’ all-grey uniforms and the solipsistic sensory deprivation of the Soulex company’s amniotic ‘float spas’. But such businesses are booming. In hard times, many go minimal by default, yet others pay handsomely for the ultimate postmodern lifestyle commodity, which, Kayla observes, they can of course never possess: nothing.

The original Garden of Emptiness, Kyle Chayka explains in his pugnacious whistlestop tour of minimalism, is to be found in the 16th-century rock garden of the Kyoto Zen temple Ryoan-Ji. Chayka journeys to this sacred spot in search of the philosophical minimalism that has been obscured by today’s commodified decluttering. His book, which ranges from the Stoics and Buddhism to Mies van der Rohe, is a rebuke to the Shintoistic declutterer Marie Kondo, whose bestselling Netflix-powered KonMari method urges us to retain only those possessions that ‘spark joy’ and to practise such techniques as folding trousers vertically and not – heavens! – horizontally. Chayka warms to Donald Judd’s Plexiglas, Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Brian Eno’s ‘Discreet Music’. He is irked by minimalist hipsters’ all-grey uniforms and the solipsistic sensory deprivation of the Soulex company’s amniotic ‘float spas’. But such businesses are booming. In hard times, many go minimal by default, yet others pay handsomely for the ultimate postmodern lifestyle commodity, which, Kayla observes, they can of course never possess: nothing. In 1994, the term ‘straight to TV movie’ was used mostly as an insult. So when a small film called The Last Seduction premiered on HBO, nobody expected much. But those who caught it were floored by a darkly comic noir thriller with a knockout performance from Linda Fiorentino as Bridget Gregory. Bridget is a smart-talking New Yorker who hits ‘cow country’ with a suitcase of cash her husband Clay (Bill Pullman) had acquired in a drug deal. Advised to lie low for a while, Bridget shacks up with smitten local Mike (Peter Berg) and uses him to enact a devious plan. Directed by John Dahl and written by Steve Barancik, The Last Seduction is bitterly funny and deliciously clever – the razor-sharp dialogue is loaded with one-liners. It’s also sexy in a way that appeals to both women and men. With its manipulative femme fatale, it touches on similar themes to the big-budget Basic Instinct – but many believe it does it much better.

In 1994, the term ‘straight to TV movie’ was used mostly as an insult. So when a small film called The Last Seduction premiered on HBO, nobody expected much. But those who caught it were floored by a darkly comic noir thriller with a knockout performance from Linda Fiorentino as Bridget Gregory. Bridget is a smart-talking New Yorker who hits ‘cow country’ with a suitcase of cash her husband Clay (Bill Pullman) had acquired in a drug deal. Advised to lie low for a while, Bridget shacks up with smitten local Mike (Peter Berg) and uses him to enact a devious plan. Directed by John Dahl and written by Steve Barancik, The Last Seduction is bitterly funny and deliciously clever – the razor-sharp dialogue is loaded with one-liners. It’s also sexy in a way that appeals to both women and men. With its manipulative femme fatale, it touches on similar themes to the big-budget Basic Instinct – but many believe it does it much better. Soon after the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan

Soon after the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan  This, Clive James’s final book, is a collection of his writings on Larkin and his work. James takes his title from the final words of Larkin’s ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ (1959). The ninety four pages, which include copies of one manuscript letter and two typed letters from Larkin to James, don’t offer very much book for your money, but you do get Clive James, who’s always good value. His explanation of why Jack Nicholson is the only Hollywood actor appropriate to play Larkin onscreen justifies the price of admission.

This, Clive James’s final book, is a collection of his writings on Larkin and his work. James takes his title from the final words of Larkin’s ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ (1959). The ninety four pages, which include copies of one manuscript letter and two typed letters from Larkin to James, don’t offer very much book for your money, but you do get Clive James, who’s always good value. His explanation of why Jack Nicholson is the only Hollywood actor appropriate to play Larkin onscreen justifies the price of admission. In July 1925, Margaret Mead, a doctoral student at Columbia University, set off on a cross-country train journey with a young faculty member, Ruth Benedict. Mead was bound for the west coast and then American Samoa, her first fieldwork expedition as a junior anthropologist. Benedict was stopping in New Mexico to study myth and ritual in the Zuni Pueblo. The journey took them through Ohio to Illinois, across the prairie, then south toward the deserts. It was the longest the two of them had ever spent together, certainly the longest without their husbands in tow.

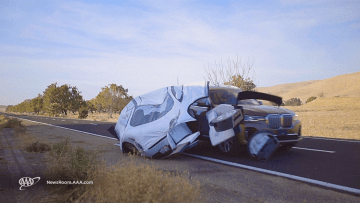

In July 1925, Margaret Mead, a doctoral student at Columbia University, set off on a cross-country train journey with a young faculty member, Ruth Benedict. Mead was bound for the west coast and then American Samoa, her first fieldwork expedition as a junior anthropologist. Benedict was stopping in New Mexico to study myth and ritual in the Zuni Pueblo. The journey took them through Ohio to Illinois, across the prairie, then south toward the deserts. It was the longest the two of them had ever spent together, certainly the longest without their husbands in tow. Recently, researchers at MIT published a study that looks into autonomous vehicle mobility, employment and policy. The research found that self-driving vehicles will happen later than sooner.

Recently, researchers at MIT published a study that looks into autonomous vehicle mobility, employment and policy. The research found that self-driving vehicles will happen later than sooner. It is becoming clear that many of our nation’s children could be attending school from home for this school year and possibly longer. If educators and families aren’t empowered with the right support and tools, this will evolve from an education crisis to an education catastrophe.

It is becoming clear that many of our nation’s children could be attending school from home for this school year and possibly longer. If educators and families aren’t empowered with the right support and tools, this will evolve from an education crisis to an education catastrophe. Since 1964, the presidential candidate who has won Florida and its 29 electoral college votes has also won the White House in every election except 1992. In that time, the constant has not been whether Florida goes for Republicans or Democrats – both parties have been in power in the past three decades – but that the vote has been close. In 2016, Donald Trump won with 48.6 per cent of the vote compared to Hillary Clinton’s 47.4 percent. In 2008, Barack Obama had 51 percent, compared to John McCain’s 48.2. And no one, of course, can forget the 2000 election, which

Since 1964, the presidential candidate who has won Florida and its 29 electoral college votes has also won the White House in every election except 1992. In that time, the constant has not been whether Florida goes for Republicans or Democrats – both parties have been in power in the past three decades – but that the vote has been close. In 2016, Donald Trump won with 48.6 per cent of the vote compared to Hillary Clinton’s 47.4 percent. In 2008, Barack Obama had 51 percent, compared to John McCain’s 48.2. And no one, of course, can forget the 2000 election, which