Here is another pair of stories, one that will be more familiar to American readers. Let’s begin this one in the 1980s, when a young Lindsey Graham first served with the Judge Advocate General’s Corps—the military legal service—in the U.S. Air Force. During some of that time, Graham was based in what was then West Germany, on the cutting edge of America’s Cold War efforts. Graham, born and raised in a small town in South Carolina, was devoted to the military: After both of his parents died when he was in his 20s, he got himself and his younger sister through college with the help of an ROTC stipend and then an Air Force salary. He stayed in the Reserves for two decades, even while in the Senate, sometimes journeying to Iraq or Afghanistan to serve as a short-term reserve officer. “The Air Force has been one of the best things that has ever happened to me,” he said in 2015. “It gave me a purpose bigger than myself. It put me in the company of patriots.” Through most of his years in the Senate, Graham, alongside his close friend John McCain, was a spokesperson for a strong military, and for a vision of America as a democratic leader abroad. He also supported a vigorous notion of democracy at home. In his 2014 reelection campaign, he ran as a maverick and a centrist, telling The Atlantic that jousting with the Tea Party was “more fun than any time I’ve been in politics.”

Here is another pair of stories, one that will be more familiar to American readers. Let’s begin this one in the 1980s, when a young Lindsey Graham first served with the Judge Advocate General’s Corps—the military legal service—in the U.S. Air Force. During some of that time, Graham was based in what was then West Germany, on the cutting edge of America’s Cold War efforts. Graham, born and raised in a small town in South Carolina, was devoted to the military: After both of his parents died when he was in his 20s, he got himself and his younger sister through college with the help of an ROTC stipend and then an Air Force salary. He stayed in the Reserves for two decades, even while in the Senate, sometimes journeying to Iraq or Afghanistan to serve as a short-term reserve officer. “The Air Force has been one of the best things that has ever happened to me,” he said in 2015. “It gave me a purpose bigger than myself. It put me in the company of patriots.” Through most of his years in the Senate, Graham, alongside his close friend John McCain, was a spokesperson for a strong military, and for a vision of America as a democratic leader abroad. He also supported a vigorous notion of democracy at home. In his 2014 reelection campaign, he ran as a maverick and a centrist, telling The Atlantic that jousting with the Tea Party was “more fun than any time I’ve been in politics.”

While Graham was doing his tour in West Germany, Mitt Romney became a co-founder and then the president of Bain Capital, a private-equity investment firm. Born in Michigan, Romney worked in Massachusetts during his years at Bain, but he also kept, thanks to his Mormon faith, close ties to Utah. While Graham was a military lawyer, drawing military pay, Romney was acquiring companies, restructuring them, and then selling them. This was a job he excelled at—in 1990, he was asked to run the parent firm, Bain & Company—and in the course of doing so he became very rich. Still, Romney dreamed of a political career, and in 1994 he ran for the Senate in Massachusetts, after changing his political affiliation from independent to Republican. He lost, but in 2002 he ran for governor of Massachusetts as a nonpartisan moderate, and won. In 2007—after a gubernatorial term during which he successfully brought in a form of near-universal health care that became a model for Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act—he staged his first run for president. After losing the 2008 Republican primary, he won the party’s nomination in 2012, and then lost the general election.

Both Graham and Romney had presidential ambitions; Graham staged his own short-lived presidential campaign in 2015 (justified on the grounds that “the world is falling apart”). Both men were loyal members of the Republican Party, skeptical of the party’s radical and conspiratorial fringe. Both men reacted to the presidential candidacy of Donald Trump with real anger, and no wonder: In different ways, Trump’s values undermined their own. Graham had dedicated his career to an idea of U.S. leadership around the world—whereas Trump was offering an “America First” doctrine that would turn out to mean “me and my friends first.”

More here.

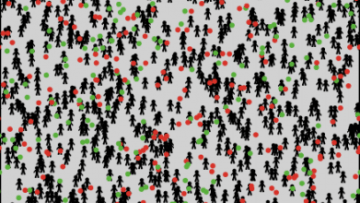

The distribution of wealth follows a well-known pattern sometimes called an 80:20 rule: 80 percent of the wealth is owned by 20 percent of the people. Indeed, a report last year concluded that just eight men had a total wealth equivalent to that of the world’s poorest 3.8 billion people.

The distribution of wealth follows a well-known pattern sometimes called an 80:20 rule: 80 percent of the wealth is owned by 20 percent of the people. Indeed, a report last year concluded that just eight men had a total wealth equivalent to that of the world’s poorest 3.8 billion people.

The key consequence of seeing the humanities as a world alongside other broadly similar worlds is that the limits of their defensibility becomes apparent, and sermonizing over them becomes harder. If people stopped watching and playing sports, how much would it matter? The question is unanswerable since we can’t imagine a society continuous with ours but lacking sports, even though one such is, I suppose, possible. We do not have the means to adjudicate between that imaginary sportless society and our own actual sports-obsessed society. The same is true for the humanities. If the humanities were to disappear, new social and cultural configurations would then exist. Would this be a loss or gain? There is no way of telling, partly because we can’t picture what a society and culture that follow from ours but lack the humanities would be like at the requisite level of detail, and partly because, even if we could imagine such a society, our judgment between a society with the humanities and one without them couldn’t appeal to the standards like ours that are embedded in the humanities themselves. The humanities would be gone: that’s it.

The key consequence of seeing the humanities as a world alongside other broadly similar worlds is that the limits of their defensibility becomes apparent, and sermonizing over them becomes harder. If people stopped watching and playing sports, how much would it matter? The question is unanswerable since we can’t imagine a society continuous with ours but lacking sports, even though one such is, I suppose, possible. We do not have the means to adjudicate between that imaginary sportless society and our own actual sports-obsessed society. The same is true for the humanities. If the humanities were to disappear, new social and cultural configurations would then exist. Would this be a loss or gain? There is no way of telling, partly because we can’t picture what a society and culture that follow from ours but lack the humanities would be like at the requisite level of detail, and partly because, even if we could imagine such a society, our judgment between a society with the humanities and one without them couldn’t appeal to the standards like ours that are embedded in the humanities themselves. The humanities would be gone: that’s it. One of my favorite Earle performances is

One of my favorite Earle performances is  Here is another

Here is another  In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the

In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden.

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden. Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings.

Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings. “One way the internet distorts our picture of ourselves is by feeding the human tendency to overestimate our knowledge of how the world works,”

“One way the internet distorts our picture of ourselves is by feeding the human tendency to overestimate our knowledge of how the world works,”  At it

At it

There’s a trope of the British Asian identity narrative, once captured with such originality and brilliance in Hanif Kureishi’s

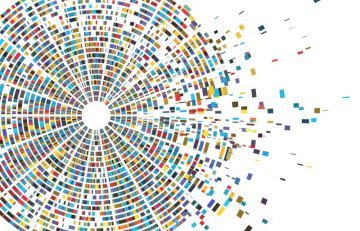

There’s a trope of the British Asian identity narrative, once captured with such originality and brilliance in Hanif Kureishi’s  With the refinement and reduced cost of sequencing technology, science has reached another inflection point: population-scale genomics, where clinical-grade assays can be used to advance healthcare, while fueling research. The Healthy Nevada Project (HNP) epitomizes that movement. A population health initiative run by the Renown Institute for Health Innovation (Renown IHI), a partnership between Renown Health and the Desert Research Institute, the project aims to combine genomic, environmental and medical data from 250,000 participants to assess the influence of genetics on health and disease. The study also uses sequencing data to screen participants for medically actionable genetic conditions, such as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), and Lynch syndrome (LS).

With the refinement and reduced cost of sequencing technology, science has reached another inflection point: population-scale genomics, where clinical-grade assays can be used to advance healthcare, while fueling research. The Healthy Nevada Project (HNP) epitomizes that movement. A population health initiative run by the Renown Institute for Health Innovation (Renown IHI), a partnership between Renown Health and the Desert Research Institute, the project aims to combine genomic, environmental and medical data from 250,000 participants to assess the influence of genetics on health and disease. The study also uses sequencing data to screen participants for medically actionable genetic conditions, such as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), and Lynch syndrome (LS).

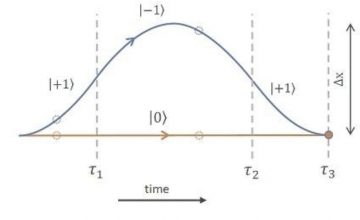

A group of theoretical physicists, including two physicists from the University of Groningen, have proposed a ‘table-top’ device that could measure gravity waves. However, their actual aim is to answer one of the biggest questions in physics: is gravity a quantum phenomenon? The key element for the device is the quantum superposition of large objects. Their design was published in New Journal of Physics on 6 August.

A group of theoretical physicists, including two physicists from the University of Groningen, have proposed a ‘table-top’ device that could measure gravity waves. However, their actual aim is to answer one of the biggest questions in physics: is gravity a quantum phenomenon? The key element for the device is the quantum superposition of large objects. Their design was published in New Journal of Physics on 6 August.