Fence

And the fence needs

built, and I

of course, say yes to

the secret language of

wire, of keep out,

of property, and respect

the landowner, then the land,

so I drive the backhoe;

the hydraulic breath, spiderlike,

blows smoke through

the brush, and

a bird is hit

by the blade I push.

A bird, the bird,

an eagle, young, ugly,

fearsome,

bald but truly

defeathered and bleeding

and peep peep peep,

the unnerving blood.

It squawks in my hand,

and I remember the words,

A fossil we can leave,

but something of life lived

before, bury and destroy. I

left smashed stones,

sharpened, and clay, hardened,

in my wake, and again,

a symbol in my hand,

and I thought to free it to

life unknown and wolves,

Think. It’s easier with chew.

But it’s gone,

and I looked up

to the hills, feeling watched,

a spine of rock, fishlike

fearsome,

sent as punishment from

God, or a god, another,

so I grabbed and twisted the feathered neck,

then buried the eagle

beneath a Copenhagen headstone,

a signpost of a secret language

that I’d try to speak

to others at home

around my five-hundred dollar table,

cast-off wood, covered in tobacco tin lids,

a hundred at five dollars, each,

and epoxy, a joke

of excess.

by Tyler Julian

from Echotheo Review

You walk into your living room to find your friends, Anne and Bob, talking about whether euthanasia is morally right or wrong. Their conversation starts in a friendly way, but when Bob claims that his view is “clearly true” Anne rolls her eyes and tells him why his view isn’t true. Anne claims that Bob’s view about euthanasia is not only not obviously true, it is not true at all. She gives a counterexample, and Bob gives his reply. Eventually their argument stops, they both sense they are going in circles. Bob turns to you and asks which view you think is true. You tell them that they need to answer another question first. Anne and Bob sigh and don the well-worn expressions of people who have a philosopher for a friend.

You walk into your living room to find your friends, Anne and Bob, talking about whether euthanasia is morally right or wrong. Their conversation starts in a friendly way, but when Bob claims that his view is “clearly true” Anne rolls her eyes and tells him why his view isn’t true. Anne claims that Bob’s view about euthanasia is not only not obviously true, it is not true at all. She gives a counterexample, and Bob gives his reply. Eventually their argument stops, they both sense they are going in circles. Bob turns to you and asks which view you think is true. You tell them that they need to answer another question first. Anne and Bob sigh and don the well-worn expressions of people who have a philosopher for a friend. Among the several hundred people who signed up for this newsletter within two days of its launch, I recognised the e-mail addresses of perhaps twenty percent. This means that, for the rest, I have no idea at all what you know of me. So, briefly, I am, among other things, a professor of philosophy, American by birth, based in Paris since 2012.

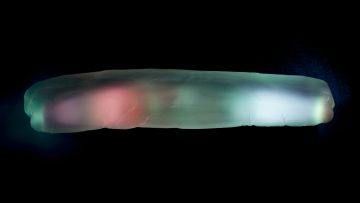

Among the several hundred people who signed up for this newsletter within two days of its launch, I recognised the e-mail addresses of perhaps twenty percent. This means that, for the rest, I have no idea at all what you know of me. So, briefly, I am, among other things, a professor of philosophy, American by birth, based in Paris since 2012. Sculpture parks proliferated, worldwide, in the second half of the twentieth century, in the wake of an identity crisis for large three-dimensional art. Modernist austerity had stripped sculpture of its traditional architectural and civic functions: there were no more integrated niches and pedestals, few new formal gardens, and an epochal apathy regarding statues—until lately! (We are now practically neo-Victorian in our awakenings—rude, for the most part—to symbolism in statuary.) Never mind the odd plaza-plunked, vaguely humanist Henry Moore. Where could one put outsized works that were almost invariably abstract—modernism’s universalist ideals persisting—to give them a chance of seeming to mean something? In nature! Conjoining the made with the unmade, gratifying both. Sculpture parks emerged as game preserves and laboratories for big art. Storm King’s early concentration of works by relevant artists of the late nineteen-sixties and seventies includes some formulaic banalities, tending to presume a surefire magic in embowered angular geometry, but even there you may savor the zest of a moment when sculpture jumped into nature’s lap. The history is complicated and obscured, in the art world, by the contemporaneous development, in the sixties, of Minimalism, which, by engaging the physical presence of viewers, shrugs off its surroundings.

Sculpture parks proliferated, worldwide, in the second half of the twentieth century, in the wake of an identity crisis for large three-dimensional art. Modernist austerity had stripped sculpture of its traditional architectural and civic functions: there were no more integrated niches and pedestals, few new formal gardens, and an epochal apathy regarding statues—until lately! (We are now practically neo-Victorian in our awakenings—rude, for the most part—to symbolism in statuary.) Never mind the odd plaza-plunked, vaguely humanist Henry Moore. Where could one put outsized works that were almost invariably abstract—modernism’s universalist ideals persisting—to give them a chance of seeming to mean something? In nature! Conjoining the made with the unmade, gratifying both. Sculpture parks emerged as game preserves and laboratories for big art. Storm King’s early concentration of works by relevant artists of the late nineteen-sixties and seventies includes some formulaic banalities, tending to presume a surefire magic in embowered angular geometry, but even there you may savor the zest of a moment when sculpture jumped into nature’s lap. The history is complicated and obscured, in the art world, by the contemporaneous development, in the sixties, of Minimalism, which, by engaging the physical presence of viewers, shrugs off its surroundings. Across Storm King’s open fields and rolling meadows are giant works by Sol LeWitt, Alice Aycock, Ursula von Rydingsvard; ensconced within the paths of a wood is smaller, earlier statuary by names grown obscure, as well as a weathered, trowel-nicked concrete slab by

Across Storm King’s open fields and rolling meadows are giant works by Sol LeWitt, Alice Aycock, Ursula von Rydingsvard; ensconced within the paths of a wood is smaller, earlier statuary by names grown obscure, as well as a weathered, trowel-nicked concrete slab by  To Donald Trump, it’s “

To Donald Trump, it’s “ When I first moved to Washington, I attended a party at Blair House, which stands across Lafayette Square from the White House. Visiting dignitaries are often put up there. A tour was led by the chief of protocol, a fragile southerner obsessed with discretion who kept vowing never to write a book about the scandals he had seen, which he kept referring to in a veiled way. The history of the house was poignant. There was the room where Robert E. Lee was offered by

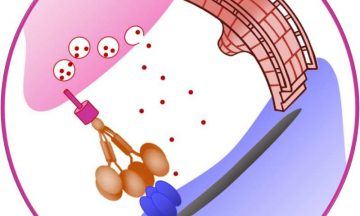

When I first moved to Washington, I attended a party at Blair House, which stands across Lafayette Square from the White House. Visiting dignitaries are often put up there. A tour was led by the chief of protocol, a fragile southerner obsessed with discretion who kept vowing never to write a book about the scandals he had seen, which he kept referring to in a veiled way. The history of the house was poignant. There was the room where Robert E. Lee was offered by  The human brain’s neuronal network undergoes lifelong changes in order to be able to assimilate information and store it in a suitable manner. This applies in particular to the generation and recall of memories. So-called synapses play a central role in the brain’s ability to adapt. They are junctions through which nerve signals are passed from one cell to the next. A number of specific molecules known as synaptic organizing proteins ensure that synapses are formed and reconfigured whenever necessary.

The human brain’s neuronal network undergoes lifelong changes in order to be able to assimilate information and store it in a suitable manner. This applies in particular to the generation and recall of memories. So-called synapses play a central role in the brain’s ability to adapt. They are junctions through which nerve signals are passed from one cell to the next. A number of specific molecules known as synaptic organizing proteins ensure that synapses are formed and reconfigured whenever necessary. Lauren Nichols

Lauren Nichols I’ve been hearing a lot about blockchain in the last few years. I mean, who hasn’t? It’s everywhere.

I’ve been hearing a lot about blockchain in the last few years. I mean, who hasn’t? It’s everywhere. JACQUES RIVETTE: When I began making films my point of view was that of a cinephile, so my ideas about what I wanted to do were abstract. Then, after the experience of my first two films, I realised I had taken the wrong direction as regards methods of shooting. The cinema of mise en scène, where everything is carefully preplanned and where you try to ensure that what is seen on the screen corresponds as closely as possible to your original plan, was not a method in which I felt at ease or worked well. What bothered me from the outset, after I had finally managed to finish Paris Nous Appartient with all its tribulations, was what the characters said, the words they used. I had written the dialogue beforehand with my co-writer Jean Gruault (though I was 90 per cent responsible) and then it was reworked and pruned during shooting, as the film otherwise would have run four-and-a-half hours. The actors sometimes changed a word here and there, as always happens in films, but basically the dialogue was what I had written – and I found it a source of intense embarrassment. So much so that when I began work on La Religieuse, which was a project that took quite a while to get off the ground, I determined this time to use what was basically a pre-existing text.

JACQUES RIVETTE: When I began making films my point of view was that of a cinephile, so my ideas about what I wanted to do were abstract. Then, after the experience of my first two films, I realised I had taken the wrong direction as regards methods of shooting. The cinema of mise en scène, where everything is carefully preplanned and where you try to ensure that what is seen on the screen corresponds as closely as possible to your original plan, was not a method in which I felt at ease or worked well. What bothered me from the outset, after I had finally managed to finish Paris Nous Appartient with all its tribulations, was what the characters said, the words they used. I had written the dialogue beforehand with my co-writer Jean Gruault (though I was 90 per cent responsible) and then it was reworked and pruned during shooting, as the film otherwise would have run four-and-a-half hours. The actors sometimes changed a word here and there, as always happens in films, but basically the dialogue was what I had written – and I found it a source of intense embarrassment. So much so that when I began work on La Religieuse, which was a project that took quite a while to get off the ground, I determined this time to use what was basically a pre-existing text. “[Jacques Rivette’s] whole movie, like a dream, is set between quotation marks,” Gilbert Adair suggested in Film Comment in 1974. “Like a dream, it is an anagram of reality.” The simplest way to explain the film – if there is a simple way to explain it – is that at some point Celine enters a remote mansion on the outskirts of the city, loses track of time, and ends up thrown back into daylight after an unspecified number of hours. She is dazed, and has no memory of what occurred inside the house, but feels compelled to keep returning.

“[Jacques Rivette’s] whole movie, like a dream, is set between quotation marks,” Gilbert Adair suggested in Film Comment in 1974. “Like a dream, it is an anagram of reality.” The simplest way to explain the film – if there is a simple way to explain it – is that at some point Celine enters a remote mansion on the outskirts of the city, loses track of time, and ends up thrown back into daylight after an unspecified number of hours. She is dazed, and has no memory of what occurred inside the house, but feels compelled to keep returning. The larger question lurking behind the debate over “cancel culture” is the one about liberalism—to wit, what is liberalism, anyway? And why should we care about it? I signed the Harper’s “

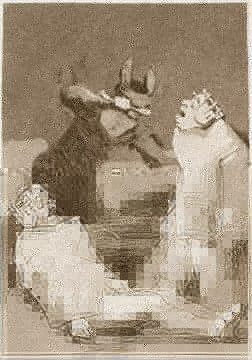

The larger question lurking behind the debate over “cancel culture” is the one about liberalism—to wit, what is liberalism, anyway? And why should we care about it? I signed the Harper’s “ A young Ernest Hemingway, badly injured by an exploding shell on a World War I battlefield, wrote in a letter home that “dying is a very simple thing. I’ve looked at death, and really I know. If I should have died it would have been very easy for me. Quite the easiest thing I ever did.” Years later Hemingway adapted his own experience—that of the soul leaving the body, taking flight and then returning—for his famous short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” about an African safari gone disastrously wrong. The protagonist, stricken by gangrene, knows he is dying. Suddenly, his pain vanishes, and Compie, a bush pilot, arrives to rescue him. The two take off and fly together through a storm with rain so thick “it seemed like flying through a waterfall” until the plane emerges into the light: before them, “unbelievably white in the sun, was the square top of Kilimanjaro. And then he knew that there was where he was going.” The description embraces elements of a classic near-death experience: the darkness, the cessation of pain, the emerging into the light and then a feeling of peacefulness.

A young Ernest Hemingway, badly injured by an exploding shell on a World War I battlefield, wrote in a letter home that “dying is a very simple thing. I’ve looked at death, and really I know. If I should have died it would have been very easy for me. Quite the easiest thing I ever did.” Years later Hemingway adapted his own experience—that of the soul leaving the body, taking flight and then returning—for his famous short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” about an African safari gone disastrously wrong. The protagonist, stricken by gangrene, knows he is dying. Suddenly, his pain vanishes, and Compie, a bush pilot, arrives to rescue him. The two take off and fly together through a storm with rain so thick “it seemed like flying through a waterfall” until the plane emerges into the light: before them, “unbelievably white in the sun, was the square top of Kilimanjaro. And then he knew that there was where he was going.” The description embraces elements of a classic near-death experience: the darkness, the cessation of pain, the emerging into the light and then a feeling of peacefulness.