Category: Recommended Reading

Saturday, September 5, 2020

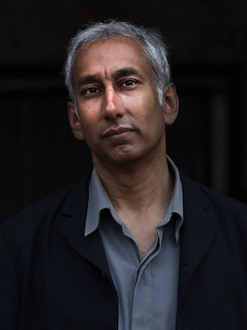

Chris Bertram and Kenan Malik Debate “White Privilege”

Over at Crooked Timber, first Chris Bertram:

Over at Crooked Timber, first Chris Bertram:

The term “white privilege” has been getting a lot of play and a lot of pushback recently, for example, from Kenan Malik in this piece and there are some parallels in the writing of people like Adolph Reed who want to stress class-based solidarity over race. Often it isn’t clear what the basic objection from “class” leftists to the concept of “white privilege” is. Sometimes the objection seems to be a factual one: that no such thing exists or that insofar as there is something, then it is completely captured by claims about racism, so that the term “white privilege” is redundant. Alternatively, the objection is occasionally strategic or pragmatic: the fight for social justice requires an alliance that crosses racial and other identity boundaries and terms like “white privilege” sow division and make that struggle more difficult. These objections are, though, logically independent of one another: “white privilege” could be real, but invoking it could be damaging to the struggle; or it could be pragmatically useful for justice even if somewhat nebulous and explanatorily empty.

More here.

Kenan Malik:

In the first post, Chris argues that “the ‘white privilege’ claim sits best with a certain sort of metaphysics of the person, such that individuals have a range of characteristics, some of which are more natural and others more social, that confer a competitive advantage or disadvantage in a given environment, where that environment is constituted by a range of elements, including demographics, institutions, cultural practices, individual attitudes, and so forth.”

But he also acknowledges that “I’m not establishing that, as a matter of fact, “white privilege” in the form I describe is a real thing, although I believe that it is”. It is difficult to see, though, how one can have a debate about whether “white privilege” is a meaningful category without have first established whether it is “a real thing”. It is possible to have an abstract debate about whether such a phenomenon could exist, but not to critique those who challenge the concept as inchoate in reality. Chris, in common with many proponents of the “white privilege” thesis, takes as given that which has to be demonstrated.

More here.

Germany finds it hard to love Hegel 250 years after his birth

Philip Oltermann in The Guardian:

Philip Oltermann in The Guardian:

In March 1807, aged 36, a towering giant of German philosophy was struggling to come to terms with a career dip.

With an illegitimate son to support and a patrimonial inheritance run dry, George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel had chucked in an unpaid academic post and accepted a job as an editor at a local newspaper in Bamberg, where he was compiling reports on royal boar hunts. Only a newly acquired coffee percolator offered brief caffeinated thrills.

To make things worse, friends got in touch with feedback on his recently completed 600-page magnus opus, The Phenomenology of the Spirit. They found it hard going.

The man Bertrand Russell later described as “the hardest to understand of the great philosophers” responded with a rare moment of self-doubt. Sometimes, he conceded, it was “easier to be sublimely unintelligible than to be comprehensible in a simple way”.

More here.

On Witness and Respair: A Personal Tragedy Followed by Pandemic

Jesmyn Ward in Vanity Fair:

Jesmyn Ward in Vanity Fair:

My Beloved died in January. He was a foot taller than me and had large, beautiful dark eyes and dexterous, kind hands. He fixed me breakfast and pots of loose-leaf tea every morning. He cried at both of our children’s births, silently, tears glazing his face. Before I drove our children to school in the pale dawn light, he would put both hands on the top of his head and dance in the driveway to make the kids laugh. He was funny, quick-witted, and could inspire the kind of laughter that cramped my whole torso. Last fall, he decided it would be best for him and our family if he went back to school. His primary job in our household was to shore us up, to take care of the children, to be a househusband. He traveled with me often on business trips, carried our children in the back of lecture halls, watchful and quietly proud as I spoke to audiences, as I met readers and shook hands and signed books. He indulged my penchant for Christmas movies, for meandering trips through museums, even though he would have much preferred to be in a stadium somewhere, watching football. One of my favorite places in the world was beside him, under his warm arm, the color of deep, dark river water.

In early January, we became ill with what we thought was flu. Five days into our illness, we went to a local urgent care center, where the doctor swabbed us and listened to our chests. The kids and I were diagnosed with flu; my Beloved’s test was inconclusive. At home, I doled out medicine to all of us: Tamiflu and Promethazine. My children and I immediately began to feel better, but my Beloved did not. He burned with fever. He slept and woke to complain that he thought the medicine wasn’t working, that he was in pain. And then he took more medicine and slept again.

Two days after our family doctor visit, I walked into my son’s room where my Beloved lay, and he panted: Can’t. Breathe.

More here.

To be creative, Chinese philosophy teaches us to abandon ‘originality’

Julianne Chung in Psyche:

Julianne Chung in Psyche:

When I was 15, one of my closest friends died unexpectedly. Our physics teacher broke the news to me after I’d sat an exam, having wondered all the way through why my friend wasn’t there doing the same. I still don’t have the words to describe how I felt: it was something approaching shock, distress, disorientation. I didn’t know what to think, much less what to do. I spent many nights awake and many days in a daze.

Fifteen years later, when I was in graduate school, another friend died suddenly, a man I loved very much. I remember checking my phone and finding out, to my dismay, via text message. But while my initial response was much the same as before, there was a palpable difference in how I felt later on. While I was again surprised and saddened, I was much less disoriented than I’d been as a teenager. I could still think, and I could still get things done. It seemed to me that I’d become better at living with loss.

You might think that the reason for this difference is obvious – I was older, and I’d had more experience in coping with death. But raw experience alone isn’t enough: what matters more is whether we learn from experience. And learning from experience, especially an experience as difficult as the death of a loved one, can involve quite a lot. Among other things, it can involve creativity.

This claim might seem surprising. After all, creativity is often associated with the idea of a lone creative genius, an individual who not only excels at what they do, but also transforms the world in the process. Further, even if we don’t limit ourselves to romantic or heroic perspectives on the nature and value of creativity, it’s commonly thought that creativity at least aims at novelty or originality.

This way of thinking about creativity isn’t universal. The Zhuangzi (莊子), a classical Chinese philosophical and literary text, provides a different perspective.

More here.

Iran’s #MeToo movement challenges patriarchy and western stereotypes

Sara Tafakori in openDemocracy:

Sara Tafakori in openDemocracy:

It’s been called an Iranian #MeToo movement, and it is. Thousands of women in Iran – and some men – are going online to speak about the sexual assault and harassment they experienced. What is crucially important, at what promises to be a historic turning point in Iranian women’s struggle for their rights, is to set the movement clearly in its proper local and global context, rather than locating it in terms of the familiar binaries of East and West, as much of the coverage in the coming weeks and months will do.

This is an article which has been in the making for years, although I never thought there would be a revolutionary online commitment to naming names and to speaking out against #rape (#Tajavaz), #sexual harassment (#Azar-e Jensi), and #perpetrators (#Motajaves). Nor, probably, did the brave women who – unlike me – have spoken out against their abusers. It’s been over two weeks now: hashtags are still pouring out, naming more names, and it does not seem that they are going to stop soon. ‘Let’s build a hashtag storm’, said a tweet.

More here.

The Lives of Lucian Freud

Elizabeth Lowry at The Guardian:

In 1995 the art critic David Sylvester caused a stir by suggesting in the Guardian that Lucian Freud – by then 73 and widely acknowledged as a major figurative British artist – was “not a real painter”. Freud, Sylvester wrote, lacked natural talent but had achieved his success through “a huge effort of will applied to the realisation of a highly personal and searching vision of the world”. Was Sylvester right? It’s pretty obvious from the clenched distortions of Freud’s apprentice portraits that his innate weaknesses contributed as much as his strengths to the development of a distinctive approach. Nor was he, in the course of a 70-year career, ever much interested in composition, disliking the element of stagecraft involved. And yet somehow the result of a lifetime of ferocious application was a style that is as singular as that of Rembrandt or Frans Hals.

In 1995 the art critic David Sylvester caused a stir by suggesting in the Guardian that Lucian Freud – by then 73 and widely acknowledged as a major figurative British artist – was “not a real painter”. Freud, Sylvester wrote, lacked natural talent but had achieved his success through “a huge effort of will applied to the realisation of a highly personal and searching vision of the world”. Was Sylvester right? It’s pretty obvious from the clenched distortions of Freud’s apprentice portraits that his innate weaknesses contributed as much as his strengths to the development of a distinctive approach. Nor was he, in the course of a 70-year career, ever much interested in composition, disliking the element of stagecraft involved. And yet somehow the result of a lifetime of ferocious application was a style that is as singular as that of Rembrandt or Frans Hals.

more here.

Remembering Odetta

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

“Next a lone spotlight shone on Odetta wearing a dark loose-fitting dress, and she began singing ‘Water Boy,’ or, rather, she unleashed it. Accompanying herself with her large National acoustic guitar, eyes closed, brows knitted in concentration, she brought the full tragedy and anger of chain gang life to bear.”

“Next a lone spotlight shone on Odetta wearing a dark loose-fitting dress, and she began singing ‘Water Boy,’ or, rather, she unleashed it. Accompanying herself with her large National acoustic guitar, eyes closed, brows knitted in concentration, she brought the full tragedy and anger of chain gang life to bear.”

It was a mesmerizing performance. Odetta was drawing on spiritual patrons that included not just Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey and Lead Belly; with her classically trained voice, she put listeners in mind of the contralto Marian Anderson.

There was a second mesmerizing aspect to Odetta’s performance: her natural hair. This was years before the “Black is beautiful” movement, and unstraightened hair was a real rarity — so much so that, for a time, the cut was called “an Odetta.”

more here.

Odetta – Waterboy

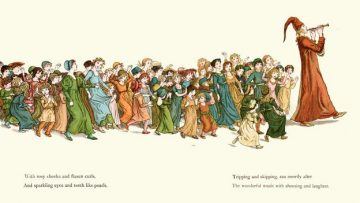

the grim truth behind the pied piper

Raphael Kadushin in BBC:

The tale in fact has survived for a very long time. Originating as medieval folklore, the story inspired a Goethe verse, Der Rattenfänger; a Grimm Brothers’ legend, The Children of Hamelin; and one of Robert Browning’s best-known poems, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. And although each writer tinkered with the story, the basics remained the same: the Piper was hired by Hamelin to rid the town of its plague of rats. Trailing after the hypnotic notes of the rat-catcher’s magical flute, the rodents politely filed through the city gates to their presumed doom.

The tale in fact has survived for a very long time. Originating as medieval folklore, the story inspired a Goethe verse, Der Rattenfänger; a Grimm Brothers’ legend, The Children of Hamelin; and one of Robert Browning’s best-known poems, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. And although each writer tinkered with the story, the basics remained the same: the Piper was hired by Hamelin to rid the town of its plague of rats. Trailing after the hypnotic notes of the rat-catcher’s magical flute, the rodents politely filed through the city gates to their presumed doom.

They weren’t the only ones lured by his music, though. When the town refused to pay the Piper for his service, the saviour turned into a more satanic seducer and came for Hamelin’s children. Entranced by the notes of his flute, the transfixed boys and girls followed the Piper out of town and simply vanished.

While the tale has endured, so has Hamelin itself, which still looks as though it belongs in a fairy tale. Boyer’s tour leads visitors past rows of half-timbered houses. There are 16th Century burgher manors encrusted with Gothic gables and scrollwork, and flamboyant wedding cake buildings offering prime examples of the local Weser-Renaissance architecture, all leering gargoyles and brightly coloured polychrome wood carvings. However, all this is merely background for the town’s real cottage industry, which cashes in on all things Piper. The local restaurants plate a “rat tail” signature dish made from thinly sliced pork, and the bakeries do a brisk business in rodent-shaped breads and cakes. The Hameln Museum offers a sound and light Pied Piper re-enactment; local actors put on an open-air Pied Piper play during summer; and the souvenir shops hawk their own rat-inspired memorabilia. You can go home, if you wish, loaded down with Pied Piper T-shirts, fridge magnets, mugs and flutes.

More here.

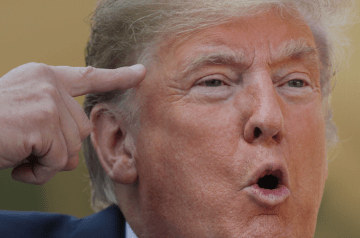

Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’

Jeffrey Goldberg in The Atlantic:

When President Donald Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris in 2018, he blamed rain for the last-minute decision, saying that “the helicopter couldn’t fly” and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true. Trump rejected the idea of the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain, and because he did not believe it important to honor American war dead, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the discussion that day. In a conversation with senior staff members on the morning of the scheduled visit, Trump said, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” In a separate conversation on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed.

When President Donald Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris in 2018, he blamed rain for the last-minute decision, saying that “the helicopter couldn’t fly” and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true. Trump rejected the idea of the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain, and because he did not believe it important to honor American war dead, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the discussion that day. In a conversation with senior staff members on the morning of the scheduled visit, Trump said, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” In a separate conversation on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed.

Belleau Wood is a consequential battle in American history, and the ground on which it was fought is venerated by the Marine Corps. America and its allies stopped the German advance toward Paris there in the spring of 1918. But Trump, on that same trip, asked aides, “Who were the good guys in this war?” He also said that he didn’t understand why the United States would intervene on the side of the Allies. Trump’s understanding of concepts such as patriotism, service, and sacrifice has interested me since he expressed contempt for the war record of the late Senator John McCain, who spent more than five years as a prisoner of the North Vietnamese. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said in 2015 while running for the Republican nomination for president. “I like people who weren’t captured.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

Greetings to the People of Europe

Over land and sea, your fathers came to Africa

and unpacked bibles by the thousand,

filling our ancestors with words of love:

if someone slaps your right cheek,

let him slap your left cheek too!

if someone takes your coat,

let him have your trousers too!

now we, their children’s children,

inheriting the words your fathers left behind,

our bodies slapped and stripped

by our lifetime presidents,

are braving seas and leaky boats,

cold waves of fear – let salt winds punch

our faces and your coast-guards

pluck us from the water like oily birds!

but here we are at last to knock

at your front door,

hoping against hope that you remember

all the lovely words your fathers preached to ours.

by Alemu Tebeje

from: Songs We Learn From Trees

Carcanet Classics, Manchester

Friday, September 4, 2020

David Graeber, anthropologist and author of Bullshit Jobs, dies aged 59

Sian Cain in The Guardian:

David Graeber, anthropologist and anarchist author of bestselling books on bureaucracy and economics including Bullshit Jobs: A Theory and Debt: The First 5,000 Years, has died aged 59.

David Graeber, anthropologist and anarchist author of bestselling books on bureaucracy and economics including Bullshit Jobs: A Theory and Debt: The First 5,000 Years, has died aged 59.

On Thursday Graeber’s wife, the artist and writer Nika Dubrovsky, announced on Twitter that Graeber had died in hospital in Venice the previous day. The cause of death is not yet known.

Renowned for his biting and incisive writing about bureaucracy, politics and capitalism, Graeber was a leading figure in the Occupy Wall Street movement and professor of anthropology at the London School of Economics (LSE) at the time of his death. His final book, The Dawn of Everything: a New History of Humanity, written with David Wengrow, will be published in autumn 2021.

The historian Rutger Bregman called Graeber “one of the greatest thinkers of our time and a phenomenal writer”, while the Guardian columnist Owen Jones called him “an intellectual giant, full of humanity, someone whose work inspired and encouraged and educated so many”.

More here. [David also won a 3QD Prize in 2011, after which I corresponded with him a bit and he was charming. He will be missed.]

Your Guide to the Many Meanings of Quantum Mechanics

Sabine Hossenfelder in Nautilus:

Quantum mechanics is more than a century old, but physicists still fight over what it means. Most of the hand wringing and knuckle cracking in their debates goes back to an assumption known as “realism.” This is the idea that science describes something—which we call “reality”—external to us, and to science. It’s a mode of thinking that comes to us naturally. It agrees well with our experience that the universe doesn’t seem to care what theories we have about it. Scientific history also shows that as empirical knowledge increases, we tend to converge on a shared explanation. This certainly suggests that science is somehow closing in on “the truth” about “how things really are.”

Quantum mechanics is more than a century old, but physicists still fight over what it means. Most of the hand wringing and knuckle cracking in their debates goes back to an assumption known as “realism.” This is the idea that science describes something—which we call “reality”—external to us, and to science. It’s a mode of thinking that comes to us naturally. It agrees well with our experience that the universe doesn’t seem to care what theories we have about it. Scientific history also shows that as empirical knowledge increases, we tend to converge on a shared explanation. This certainly suggests that science is somehow closing in on “the truth” about “how things really are.”

Alas, realism is ultimately a philosophical position that itself has no empirical basis. All we can tell for sure is whether a certain hypothesis is any good at describing what we observe. Yet whether that description is about something that is independent and external to us, the observer, is a question we cannot ourselves ever answer.

This, needless to say, is not a new conundrum, but one that philosophers have discussed for as long as there’ve been philosophers. But it is alive and kicking in the debate about interpretations of quantum mechanics today, as Jim Baggott reminds us in his new book Quantum Reality: The Quest for the Real Meaning of Quantum Mechanics. If this is the age of quantum reason, then Baggott is its Voltaire.

More here.

The Trump Era Sucks and Needs to Be Over

Matt Taibbi in his Substack Newsletter:

Donald Trump is so unlike most people, and so especially unlike anyone raised under a conventional moral framework, that he’s perpetually misdiagnosed. The words we see slapped on him most often, like “fascist” and “authoritarian,” nowhere near describe what he really is, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. It’s been proven across four years that Trump lacks the attention span or ambition required to implement a true dictatorial regime. He might not have a moral problem with the idea, but two minutes into the plan he’d leave the room, phone in hand, to throw on a robe and watch himself on Fox and Friends over a cheeseburger.

Donald Trump is so unlike most people, and so especially unlike anyone raised under a conventional moral framework, that he’s perpetually misdiagnosed. The words we see slapped on him most often, like “fascist” and “authoritarian,” nowhere near describe what he really is, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. It’s been proven across four years that Trump lacks the attention span or ambition required to implement a true dictatorial regime. He might not have a moral problem with the idea, but two minutes into the plan he’d leave the room, phone in hand, to throw on a robe and watch himself on Fox and Friends over a cheeseburger.

The elite misread of Trump is egregious because he’s an easily familiar type to the rest of America. We’re a sales culture and Trump is a salesman. Moreover he’s not just any salesman; he might be the greatest salesman ever, considering the quality of the product, i.e. himself.

More here.

Christopher Walken’s Coffee Shop

The Zealotry of J. F. Powers

Charles McGrath at The Hudson Review:

Like a lot of zealots, especially of the writerly sort, Powers was a perfectionist. His style, so clear and natural, came only with effort. His friend Sean O’Faolain liked to joke that Powers could spend a whole morning putting in a comma, and then the whole afternoon taking it out. “I don’t care to get a book out just to get a book out,” he wrote to a friend. “I’d rather make each one count—and in order to do that the way I nuts around, it takes time.” But it’s also true that Powers spent a great deal of time not writing. He insisted on going to a rented office every day—while Betty took care of cooking, cleaning, and raising the children—but, once there, he often just futzed around, reading the paper, rearranging the furniture, watching a ladybug crawl across an envelope. While in Ireland, he went to the races a lot and, like the writer in “Tinkers,” spent hours in auction houses bidding on useless stuff he couldn’t afford.

Like a lot of zealots, especially of the writerly sort, Powers was a perfectionist. His style, so clear and natural, came only with effort. His friend Sean O’Faolain liked to joke that Powers could spend a whole morning putting in a comma, and then the whole afternoon taking it out. “I don’t care to get a book out just to get a book out,” he wrote to a friend. “I’d rather make each one count—and in order to do that the way I nuts around, it takes time.” But it’s also true that Powers spent a great deal of time not writing. He insisted on going to a rented office every day—while Betty took care of cooking, cleaning, and raising the children—but, once there, he often just futzed around, reading the paper, rearranging the furniture, watching a ladybug crawl across an envelope. While in Ireland, he went to the races a lot and, like the writer in “Tinkers,” spent hours in auction houses bidding on useless stuff he couldn’t afford.

more here.

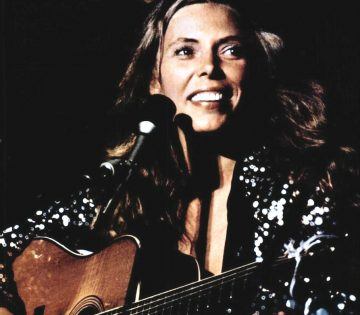

Joni Mitchell’s Ferocious Gift

Ivan Kreilkamp at Public Books:

When Joni Mitchell first came to prominence, in the late-1960s “Summer of Love” era, she was often perceived as a kind of “poetess” or “nightingale” folk singer: a putatively pure origin of beautifully natural-seeming songs (“The Circle Game,” “Chelsea Morning, and “Both Sides, Now,” among many others). When the rapper Q-Tip declared (on Janet Jackson’s 1997 song “Got ’Til it’s Gone”) that “Joni Mitchell never lies,” he articulated a familiar understanding of the singer as, above all, truthful and authentic.

When Joni Mitchell first came to prominence, in the late-1960s “Summer of Love” era, she was often perceived as a kind of “poetess” or “nightingale” folk singer: a putatively pure origin of beautifully natural-seeming songs (“The Circle Game,” “Chelsea Morning, and “Both Sides, Now,” among many others). When the rapper Q-Tip declared (on Janet Jackson’s 1997 song “Got ’Til it’s Gone”) that “Joni Mitchell never lies,” he articulated a familiar understanding of the singer as, above all, truthful and authentic.

But Mitchell’s brilliant art was always a product of artifice as much as it was of honesty. Her song “Woodstock” is now remembered as one of the most iconic musical artifacts of the late 1960s American counterculture, but it’s worth remembering that it was written by a Canadian artist who did not perform at (or even attend) Woodstock.

more here.

Joni Mitchell: Live at the Isle of Wight Festival 1970

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QpLO96_9Qwc&ab_channel=CharacterDriven

Genetics Steps In to Help Tell the Story of Human Origins

Katarina Zimmer in The Scientist:

It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box.

It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box.

The bone fragment had come from a skull—still stored at the Natural History Museum in London—with a heavy brow ridge and a large face. It looked so primitive that the miner who had discovered it in 1921 at a lead mine in the Zambian town of Kabwe, then in the British territory of Rhodesia, first thought it had belonged to a gorilla. But later that year, museum paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward noticed what he interpreted as typically human features, such as the skull’s thin and relatively large braincase, that motivated him to designate the specimen as its own hominin species.

In the 1980s, however, museum paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer took another look at the skull and classified it as belonging to the species Homo heidelbergensis, an ancient hominin thought to be a human ancestor. Based on its primitiveness, Stringer says, most researchers guessed it was an early individual who lived around half a million years ago, some 200,000 years before the earliest Homo sapiens were starting to emerge. But nobody knew exactly how old the skull was. For decades, no dating method existed that could identify the fossil’s age without the destructive process of grinding up bits of bone for analysis. But Grün was determined to find a solution.

More here.