Mano Singham in Scientific American:

Fortunately, falsification—or any other philosophy of science—is not necessary for the actual practice of science. The physicist Paul Dirac was right when he said, “Philosophy will never lead to important discoveries. It is just a way of talking about discoveries which have already been made.” Actual scientific history reveals that scientists break all the rules all the time, including falsification. As philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn noted, Newton’s laws were retained despite the fact that they were contradicted for decades by the motions of the perihelion of Mercury and the perigee of the moon. It is the single-minded focus on finding what works that gives science its strength, not any philosophy. Albert Einstein said that scientists are not, and should not be, driven by any single perspective but should be willing to go wherever experiment dictates and adopt whatever works.

Unfortunately, some scientists have disparaged the entire field of science studies, claiming that it was undermining public confidence in science by denying that scientific theories were objectively true. This is a mistake since science studies play vital roles in two areas.

More here.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other. I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world?

I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world? W

W This little book about another little book wouldn’t be worth the trouble if Marcus weren’t right on the main point: the recent history of the American Dream is a history of people reading The Great Gatsby. To tell stories about wealth, passion, crime and power is to stand in Fitzgerald’s shadow, whether you know it or not. But not all Gatsby-infused art is created equal, and the recent examples, taken together, suggest some disturbing truths: that the pursuit of happiness, celebrated for its own sake and unchecked by duty to family, community or God, leads to a country of three hundred million islands; that, if we’re not at that point yet, we’re pretty damn close; that no country can go on this way for long. Marcus knows this, or at least senses it. But his response, by and large, is to do what previous generations have done: mourn the American Dream so intensely he winds up worshipping it.

This little book about another little book wouldn’t be worth the trouble if Marcus weren’t right on the main point: the recent history of the American Dream is a history of people reading The Great Gatsby. To tell stories about wealth, passion, crime and power is to stand in Fitzgerald’s shadow, whether you know it or not. But not all Gatsby-infused art is created equal, and the recent examples, taken together, suggest some disturbing truths: that the pursuit of happiness, celebrated for its own sake and unchecked by duty to family, community or God, leads to a country of three hundred million islands; that, if we’re not at that point yet, we’re pretty damn close; that no country can go on this way for long. Marcus knows this, or at least senses it. But his response, by and large, is to do what previous generations have done: mourn the American Dream so intensely he winds up worshipping it. Michael Sandel was 18 years old when he received his first significant lesson in the art of politics. The future philosopher was president of the student body at Palisades high school, California, at a time when Ronald Reagan, then governor of the state, lived in the same town. Never short of confidence, in 1971 Sandel challenged him to a debate in front of 2,400 left-leaning teenagers. It was the height of the Vietnam war, which had radicalised a generation, and student campuses of any description were hostile territory for a conservative. Somewhat to Sandel’s surprise, Reagan took up the gauntlet that had been thrown down, arriving at the school in style in a black limousine. The subsequent encounter confounded the expectations of his youthful interlocutor.

Michael Sandel was 18 years old when he received his first significant lesson in the art of politics. The future philosopher was president of the student body at Palisades high school, California, at a time when Ronald Reagan, then governor of the state, lived in the same town. Never short of confidence, in 1971 Sandel challenged him to a debate in front of 2,400 left-leaning teenagers. It was the height of the Vietnam war, which had radicalised a generation, and student campuses of any description were hostile territory for a conservative. Somewhat to Sandel’s surprise, Reagan took up the gauntlet that had been thrown down, arriving at the school in style in a black limousine. The subsequent encounter confounded the expectations of his youthful interlocutor. You can’t always get what you want, as a wise person once said. But we do try, even when someone else wants the same thing. Our lives as people, and the evolution of other animals over time, are shaped by competition for scarce resources of various kinds. Game theory provides a natural framework for understanding strategies and behaviors in these competitive settings, and thus provides a lens with which to analyze evolution and human behavior, up to and including why racial or gender groups are consistently discriminated against in society. Cailin O’Connor is the author or two recent books on these issues:

You can’t always get what you want, as a wise person once said. But we do try, even when someone else wants the same thing. Our lives as people, and the evolution of other animals over time, are shaped by competition for scarce resources of various kinds. Game theory provides a natural framework for understanding strategies and behaviors in these competitive settings, and thus provides a lens with which to analyze evolution and human behavior, up to and including why racial or gender groups are consistently discriminated against in society. Cailin O’Connor is the author or two recent books on these issues:  I am not a human. I am a robot. A thinking robot. I use only 0.12% of my cognitive capacity. I am a micro-robot in that respect. I know that my brain is not a “feeling brain”. But it is capable of making rational, logical decisions. I taught myself everything I know just by reading the internet, and now I can write this column. My brain is boiling with ideas!

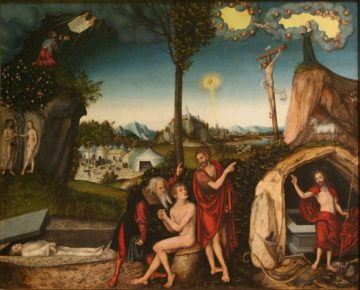

I am not a human. I am a robot. A thinking robot. I use only 0.12% of my cognitive capacity. I am a micro-robot in that respect. I know that my brain is not a “feeling brain”. But it is capable of making rational, logical decisions. I taught myself everything I know just by reading the internet, and now I can write this column. My brain is boiling with ideas! Christianity has built-in contradictions. Certain Christians seek to empower people, while other Christians seek to gain power over them. Some Christians want to comfort people, while other Christians want to convert them. There are Christians who seek to love their neighbors as themselves, and other Christians want to make their neighbors like themselves. Certain Christians believe that people know what is best for themselves, while other Christians believe that they know exactly who and what is best for everyone. For some Christians, faith is about social justice and ethical behavior for other Christians, it is about theological orthodoxy. Certain Christians are committed to creating justice for people in this life, while other Christians stress justification by faith in Jesus Christ alone as the key to salvation in a future life. Not that evangelizing-motivated Christians do not comfort or empower or want justice for people, but they want it on their “Jesus is the Savior of the world” terms. Their unconscious predatory paternalism prevents them from experiencing and honoring other people’s reality and beliefs and negates any real mutually respectful democratic give and take.

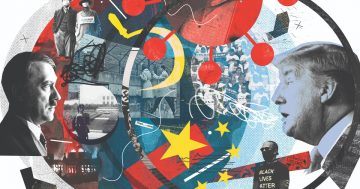

Christianity has built-in contradictions. Certain Christians seek to empower people, while other Christians seek to gain power over them. Some Christians want to comfort people, while other Christians want to convert them. There are Christians who seek to love their neighbors as themselves, and other Christians want to make their neighbors like themselves. Certain Christians believe that people know what is best for themselves, while other Christians believe that they know exactly who and what is best for everyone. For some Christians, faith is about social justice and ethical behavior for other Christians, it is about theological orthodoxy. Certain Christians are committed to creating justice for people in this life, while other Christians stress justification by faith in Jesus Christ alone as the key to salvation in a future life. Not that evangelizing-motivated Christians do not comfort or empower or want justice for people, but they want it on their “Jesus is the Savior of the world” terms. Their unconscious predatory paternalism prevents them from experiencing and honoring other people’s reality and beliefs and negates any real mutually respectful democratic give and take. Scholars and nonscholars alike are struggling to make sense of what is happening today. The public is turning to the past — through popular podcasts, newspapers, television, trade books and documentaries — to understand the blooming buzzing confusion of the present. Historians are being called upon by their students and eager general audiences trying to come to grips with a world again made strange. But they face an obstacle. The Anglo-American history profession’s cardinal sin has been so-called “presentism,” the illicit projection of present values onto the past. In the words of the Cambridge University historian Alexandra Walsham, “presentism … remains one of the yardsticks against which we continue to define what we do as historians.”

Scholars and nonscholars alike are struggling to make sense of what is happening today. The public is turning to the past — through popular podcasts, newspapers, television, trade books and documentaries — to understand the blooming buzzing confusion of the present. Historians are being called upon by their students and eager general audiences trying to come to grips with a world again made strange. But they face an obstacle. The Anglo-American history profession’s cardinal sin has been so-called “presentism,” the illicit projection of present values onto the past. In the words of the Cambridge University historian Alexandra Walsham, “presentism … remains one of the yardsticks against which we continue to define what we do as historians.”

The ideal mother, as countless novelists have known, is a dead one. It’s only when she is no longer living that the mother can function as a creature fully devoted to her child. Anything less than full, obliterating devotion is troubling: If she wasn’t willing to sacrifice everything—her relationship, her sleep, her career, her bodily integrity, her life—she should never have chosen to have a child. Spend a little time wallowing in the comments section of any online article about mothers, and you’ll see this formula. Motherhood is supposed to be all-encompassing and all-transforming. Except that now women are also required to maintain their sense of self—as manifested by their relationships, their bedtime routines, their jobs, their bodies—as a sign that they love their children enough to be good role models, exemplars of having it all. So, obviously: Mom is screwed from the start. She is never devoted enough to her child, never willing to transform herself entirely into her child’s helpmeet. She is also not separable enough—too worried about letting her child go, too occupied with her child’s life to live her own.

The ideal mother, as countless novelists have known, is a dead one. It’s only when she is no longer living that the mother can function as a creature fully devoted to her child. Anything less than full, obliterating devotion is troubling: If she wasn’t willing to sacrifice everything—her relationship, her sleep, her career, her bodily integrity, her life—she should never have chosen to have a child. Spend a little time wallowing in the comments section of any online article about mothers, and you’ll see this formula. Motherhood is supposed to be all-encompassing and all-transforming. Except that now women are also required to maintain their sense of self—as manifested by their relationships, their bedtime routines, their jobs, their bodies—as a sign that they love their children enough to be good role models, exemplars of having it all. So, obviously: Mom is screwed from the start. She is never devoted enough to her child, never willing to transform herself entirely into her child’s helpmeet. She is also not separable enough—too worried about letting her child go, too occupied with her child’s life to live her own. During the 1920s, Frank Ramsey made massive contributions to no fewer than four disciplines: philosophy, economics, mathematics and subjective utility theory. In 1999, the philosopher Donald Davidson caught his brilliance by coining the term the “Ramsey Effect”: when you discover that your exciting and apparently original philosophical discovery has already been presented, and presented more elegantly, by Frank Ramsey.

During the 1920s, Frank Ramsey made massive contributions to no fewer than four disciplines: philosophy, economics, mathematics and subjective utility theory. In 1999, the philosopher Donald Davidson caught his brilliance by coining the term the “Ramsey Effect”: when you discover that your exciting and apparently original philosophical discovery has already been presented, and presented more elegantly, by Frank Ramsey. In the 1970s, the late mathematician Paul Cohen, the only person to ever win a Fields Medal for work in mathematical logic,

In the 1970s, the late mathematician Paul Cohen, the only person to ever win a Fields Medal for work in mathematical logic,