Elizabeth Pennisi in Science:

When the human genome was sequenced almost 20 years ago, many researchers were confident they’d be able to quickly home in on the genes responsible for complex diseases such as diabetes or schizophrenia. But they stalled fast, stymied in part by their ignorance of the system of switches that govern where and how genes are expressed in the body. Such gene regulation is what makes a heart cell distinct from a brain cell, for example, and distinguishes tumors from healthy tissue. Now, a massive, decadelong effort has begun to fill in the picture by linking the activity levels of the 20,000 protein-coding human genes, as shown by levels of their RNA, to variations in millions of stretches of regulatory DNA.

When the human genome was sequenced almost 20 years ago, many researchers were confident they’d be able to quickly home in on the genes responsible for complex diseases such as diabetes or schizophrenia. But they stalled fast, stymied in part by their ignorance of the system of switches that govern where and how genes are expressed in the body. Such gene regulation is what makes a heart cell distinct from a brain cell, for example, and distinguishes tumors from healthy tissue. Now, a massive, decadelong effort has begun to fill in the picture by linking the activity levels of the 20,000 protein-coding human genes, as shown by levels of their RNA, to variations in millions of stretches of regulatory DNA.

By looking at up to 54 kinds of tissue in hundreds of recently deceased people, the $150 million Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project set out to create “one-stop shopping for the genetics of gene regulation,” says GTEx team member Emmanouil Dermitzakis, a geneticist at the University of Geneva. In a brace of papers in Science, Science Advances, Cell, and other journals this week, GTEx researchers roll out the final big analyses of these free, downloadable data, as well as tools for further exploiting the data.

More here.

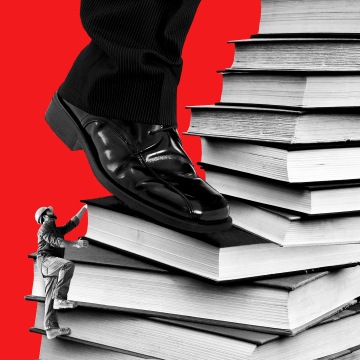

Being untainted by the Ivy League credentials of his predecessors may enable Mr. Biden to connect more readily with the blue-collar workers the Democratic Party has struggled to attract in recent years. More important, this aspect of his candidacy should prompt us to reconsider the meritocratic political project that has come to define contemporary liberalism.

Being untainted by the Ivy League credentials of his predecessors may enable Mr. Biden to connect more readily with the blue-collar workers the Democratic Party has struggled to attract in recent years. More important, this aspect of his candidacy should prompt us to reconsider the meritocratic political project that has come to define contemporary liberalism. Many Americans trusted intuition to help guide them through this disaster. They grabbed onto whatever solution was most prominent in the moment, and bounced from one (often false) hope to the next. They saw the actions that individual people were taking, and blamed and shamed their neighbors. They lapsed into magical thinking, and believed that the world would return to normal within months. Following these impulses was simpler than navigating a web of solutions, staring down broken systems, and accepting that the pandemic would rage for at least a year.

Many Americans trusted intuition to help guide them through this disaster. They grabbed onto whatever solution was most prominent in the moment, and bounced from one (often false) hope to the next. They saw the actions that individual people were taking, and blamed and shamed their neighbors. They lapsed into magical thinking, and believed that the world would return to normal within months. Following these impulses was simpler than navigating a web of solutions, staring down broken systems, and accepting that the pandemic would rage for at least a year. Before the young in this country ever stop racism, much less enact socialism, they better start by changing our form of government. Thanks to the U.S. Senate, the government still overrepresents the racist and populist parts of the country. It also now overrepresents the rural areas or underpopulated interior regions that are the biggest losers in the global economy—and by no coincidence, it has made easier the rise of Trump. Even if Republican senators from these states are by and large more genteel than the Republican members of the U.S. House, they are the real screamers, who give voice to the country’s id, or rather the parts that are most raw and red and racist.

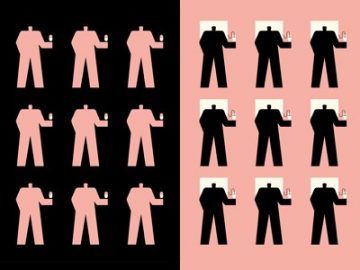

Before the young in this country ever stop racism, much less enact socialism, they better start by changing our form of government. Thanks to the U.S. Senate, the government still overrepresents the racist and populist parts of the country. It also now overrepresents the rural areas or underpopulated interior regions that are the biggest losers in the global economy—and by no coincidence, it has made easier the rise of Trump. Even if Republican senators from these states are by and large more genteel than the Republican members of the U.S. House, they are the real screamers, who give voice to the country’s id, or rather the parts that are most raw and red and racist. Early on it was commonly said that we were all in the same boat, and in fact I recall, in the early days, a unifying sensation that was not unpleasant: the slam and bolt of a nation battening down the hatches. Eighty years and a day before we entered national quarantine, Virginia Woolf had recalled a “sudden profuse shower just before the war which made me think of all men and women weeping”. There is consolation in a common grief. But it is not the same boat: it is the same storm, and different vessels weather it. It would require a wilful dereliction of the intellect to believe that the risk to a Black woman managing a hospital ward is equal to the risk to – let’s say – a columnist deploring the brief and slight curtailment of her liberty.

Early on it was commonly said that we were all in the same boat, and in fact I recall, in the early days, a unifying sensation that was not unpleasant: the slam and bolt of a nation battening down the hatches. Eighty years and a day before we entered national quarantine, Virginia Woolf had recalled a “sudden profuse shower just before the war which made me think of all men and women weeping”. There is consolation in a common grief. But it is not the same boat: it is the same storm, and different vessels weather it. It would require a wilful dereliction of the intellect to believe that the risk to a Black woman managing a hospital ward is equal to the risk to – let’s say – a columnist deploring the brief and slight curtailment of her liberty. To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see

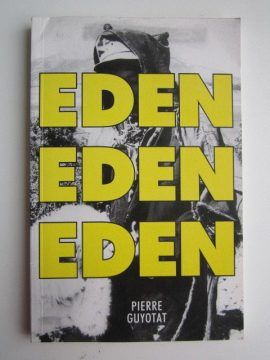

To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see  One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149).

One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149). Now fifty-eight, Rist has the energy and curiosity of an ageless child. “She’s individual and unforgettable,” the critic Jacqueline Burckhardt, one of Rist’s close friends, told me. “And she has developed a completely new video language that warms this cool medium up.” Burckhardt and her business partner, Bice Curiger, documented Rist’s career in the international art magazine Parkett, which they co-founded with others in Zurich in 1984. From the single-channel videos that Rist started making in the eighties, when she was still in college, to the immersive, multichannel installations that she creates today, she has done more to expand the video medium than any artist since the Korean-born visionary Nam June Paik. Rist once wrote that she wanted her video work to be like women’s handbags, with “room in them for everything: painting, technology, language, music, lousy flowing pictures, poetry, commotion, premonitions of death, sex, and friendliness.” If Paik is the founding father of video as an art form, Rist is the disciple who has done the most to bring it into the mainstream of contemporary art.

Now fifty-eight, Rist has the energy and curiosity of an ageless child. “She’s individual and unforgettable,” the critic Jacqueline Burckhardt, one of Rist’s close friends, told me. “And she has developed a completely new video language that warms this cool medium up.” Burckhardt and her business partner, Bice Curiger, documented Rist’s career in the international art magazine Parkett, which they co-founded with others in Zurich in 1984. From the single-channel videos that Rist started making in the eighties, when she was still in college, to the immersive, multichannel installations that she creates today, she has done more to expand the video medium than any artist since the Korean-born visionary Nam June Paik. Rist once wrote that she wanted her video work to be like women’s handbags, with “room in them for everything: painting, technology, language, music, lousy flowing pictures, poetry, commotion, premonitions of death, sex, and friendliness.” If Paik is the founding father of video as an art form, Rist is the disciple who has done the most to bring it into the mainstream of contemporary art. The internet is not what you think it is. For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as you probably imagine. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

The internet is not what you think it is. For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as you probably imagine. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other. I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world?

I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world? W

W