George Packer in The Atlantic:

There are in history what you could call ‘plastic hours,’” the philosopher Gershom Scholem once said. “Namely, crucial moments when it is possible to act. If you move then, something happens.” In such moments, an ossified social order suddenly turns pliable, prolonged stasis gives way to motion, and people dare to hope. Plastic hours are rare. They require the right alignment of public opinion, political power, and events—usually a crisis. They depend on social mobilization and leadership. They can come and go unnoticed or wasted. Nothing happens unless you move.

There are in history what you could call ‘plastic hours,’” the philosopher Gershom Scholem once said. “Namely, crucial moments when it is possible to act. If you move then, something happens.” In such moments, an ossified social order suddenly turns pliable, prolonged stasis gives way to motion, and people dare to hope. Plastic hours are rare. They require the right alignment of public opinion, political power, and events—usually a crisis. They depend on social mobilization and leadership. They can come and go unnoticed or wasted. Nothing happens unless you move.

Are we living in a plastic hour? It feels that way.

Beneath the dreary furor of the partisan wars, most Americans agree on fundamental issues facing the country. Large majorities say that government should ensure some form of universal health care, that it should do more to mitigate global warming, that the rich should pay higher taxes, that racial inequality is a significant problem, that workers should have the right to join unions, that immigrants are a good thing for American life, that the federal government is plagued by corruption. These majorities have remained strong for years. The readiness, the demand for action, is new.

What explains it? Nearly four years of a corrupt, bigoted, and inept president who betrayed his promise to champion ordinary Americans. The arrival of an influential new generation, the Millennials, who grew up with failed wars, weakened institutions, and blighted economic prospects, making them both more cynical and more utopian than their parents. Collective ills that go untreated year after year, so bone-deep and chronic that we assume they’re permanent—from income inequality, feckless government, and police abuse to a shredded social fabric and a poisonous public discourse that verges on national cognitive decline. Then, this year, a series of crises that seemed to come out of nowhere, like a flurry of sucker punches, but that arose straight from those ills and exposed the failures of American society to the world. The year 2020 began with an impeachment trial that led to acquittal despite the president’s obvious guilt. Then came the pandemic, chaotic hospital wards, ghost cities, lies and conspiracy theories from the White House, mass death, mass unemployment, police killings, nationwide protests, more sickness, more death, more economic despair, the disruption of normal life without end. Still ahead lies an election on whose outcome everything depends.

More here.

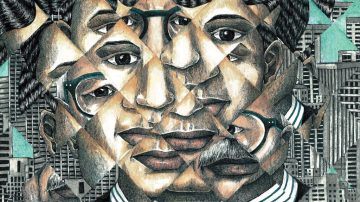

The term “super recognizer” first appeared in 2009 and describes people who can remember more than 80 percent of the faces of people they meet (the average is 20 percent). The neural-mechanism behind super recognition is still largely unknown, but the skill seems to be genetic and possessed by only about one percent of the population.

The term “super recognizer” first appeared in 2009 and describes people who can remember more than 80 percent of the faces of people they meet (the average is 20 percent). The neural-mechanism behind super recognition is still largely unknown, but the skill seems to be genetic and possessed by only about one percent of the population.

Though domestic violence constitutes one of the direst public health and criminal justice crises in the country, its gravity has been a belated and recent revelation in the American psyche, one many would still consider provisional. Around one in four American women will be harmed by a partner over the course of their lives, and while violent crime has declined in recent years, homicides due to domestic violence have not. Over half of the women killed in this country are killed by a loved one. Covid-19’s stay-at-home orders have left those suffering domestic violence more cut off from resources to protect them from abuse, including formal services like health care and shelters, as well as sites of informal social control like public playgrounds and churches, which have been shown to regulate the occurrence of abuse.

Though domestic violence constitutes one of the direst public health and criminal justice crises in the country, its gravity has been a belated and recent revelation in the American psyche, one many would still consider provisional. Around one in four American women will be harmed by a partner over the course of their lives, and while violent crime has declined in recent years, homicides due to domestic violence have not. Over half of the women killed in this country are killed by a loved one. Covid-19’s stay-at-home orders have left those suffering domestic violence more cut off from resources to protect them from abuse, including formal services like health care and shelters, as well as sites of informal social control like public playgrounds and churches, which have been shown to regulate the occurrence of abuse. One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit.” These are the opening words of the short book On Bullshit, written by the philosopher Harry Frankfurt. Fifteen years after the publication of this surprise bestseller, the rapid progress of research on artificial intelligence is forcing us to reconsider our conception of bullshit as a hallmark of human speech, with troubling implications. What do philosophical reflections on bullshit have to do with algorithms? As it turns out, quite a lot.

One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit.” These are the opening words of the short book On Bullshit, written by the philosopher Harry Frankfurt. Fifteen years after the publication of this surprise bestseller, the rapid progress of research on artificial intelligence is forcing us to reconsider our conception of bullshit as a hallmark of human speech, with troubling implications. What do philosophical reflections on bullshit have to do with algorithms? As it turns out, quite a lot.

Isabella Weber in The Guardian:

Isabella Weber in The Guardian: Jacob Bacharach in TruthDig:

Jacob Bacharach in TruthDig: Astra Taylor in The New Republic:

Astra Taylor in The New Republic: When Pauline Harmange, a French writer and aspiring novelist, published a treatise on hating men, she expected it to sell at the most a couple of hundred copies among friends and readers of her

When Pauline Harmange, a French writer and aspiring novelist, published a treatise on hating men, she expected it to sell at the most a couple of hundred copies among friends and readers of her  “Science fiction is not about the future,” the sci-fi novelist Samuel R. Delany wrote in 1984. The future “is only a writerly convention,” he continued, one that “sets up a rich and complex dialogue with the reader’s here and now.” That is a useful way of understanding all the many pop nonfiction books that speculate about the technologies of the future, and attempt to divine their effects on human beings. Their predictions depend on how well they interpret the present.

“Science fiction is not about the future,” the sci-fi novelist Samuel R. Delany wrote in 1984. The future “is only a writerly convention,” he continued, one that “sets up a rich and complex dialogue with the reader’s here and now.” That is a useful way of understanding all the many pop nonfiction books that speculate about the technologies of the future, and attempt to divine their effects on human beings. Their predictions depend on how well they interpret the present. There are in

There are in The city of Abbottabad, in the former North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, was named after James Abbott, a 19th-century British Army officer and player in the “Great Game,” the power struggle in Central Asia between the British and Russian Empires. Today it’s perhaps best known as the garrison town that sheltered Osama bin Laden before he was

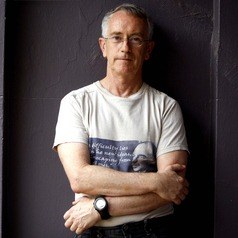

The city of Abbottabad, in the former North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, was named after James Abbott, a 19th-century British Army officer and player in the “Great Game,” the power struggle in Central Asia between the British and Russian Empires. Today it’s perhaps best known as the garrison town that sheltered Osama bin Laden before he was  Mark Blyth is stumped. He’s the people’s economist who speaks the people’s language through his thick working-class Scottish accent. He hasn’t gone silent in the pandemic ruins of our prosperity. He’s as noisy as ever, but he’s dumbfounded by his adopted people, us American people who can’t see the trouble we’re in. The hardship of the pandemic is real and unfair, he’s saying, and the problem is obvious and deep: that forty million Americans don’t have enough to eat, at the same time our billionaire class, having poisoned our politics, has grown billions richer week by week through the COVID disaster.

Mark Blyth is stumped. He’s the people’s economist who speaks the people’s language through his thick working-class Scottish accent. He hasn’t gone silent in the pandemic ruins of our prosperity. He’s as noisy as ever, but he’s dumbfounded by his adopted people, us American people who can’t see the trouble we’re in. The hardship of the pandemic is real and unfair, he’s saying, and the problem is obvious and deep: that forty million Americans don’t have enough to eat, at the same time our billionaire class, having poisoned our politics, has grown billions richer week by week through the COVID disaster. Dear H,

Dear H,