Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, Martijn Konings in the LA Review of Books:

Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, Martijn Konings in the LA Review of Books:

At the start of 2019, The Economist coined the term “millennial socialism” to refer to the growth of strong critical and left-wing sentiments in a generation that until recently was primarily known for its sense of entitlement and its obsession with social media. It noted that a large percentage of young people hold a favorable view of socialism and that “[i]n the primaries in 2016 more young folk voted for Bernie Sanders than for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump combined.” The Economist acknowledged that some of these millennials may have good reasons for their political sentiments. But it immediately went on to declare that understanding this trend shouldn’t lead us to justify or legitimate it — socialism remains as dangerous as The Economist has always known it is. It views millennial socialism as being too “pessimistic” and as wanting things that are “politically dangerous.” The Sydney Morning Herald followed up in the same month with an opinion piece arguing that while millennial socialism has roots in millennials’ “rising anxiety about their economic prospects” (and in particular the virtual impossibility of ever attaining home ownership in the country’s largest cities), as a political choice it seemed to reflect above all ignorance and the lack of memory of the horrors of communism.

Framing this political shift in terms of a generational schism would seem to rest on flimsy conceptual foundations. Indeed, while generational analysis may be making a return to public debate, where the mainstream press loves to cover millennials, among social scientists it has largely gone out of fashion. The idea that being born around the same time or experiencing the same historical events at the same age produces a natural solidarity or a similar experience of life is now considered overly simplistic. It is typically seen as too abstracted from a range of other structural inequalities that would seem to have far greater bearing on people’s position in the social hierarchy. Just as there are poor baby boomers, so there are fabulously wealthy millennials.

Yet some element of generational distinction seems to be playing an undeniable role in the logic of the present. So what do we make of this?

More here.

Edward Fishman in the Boston Review:

Edward Fishman in the Boston Review:

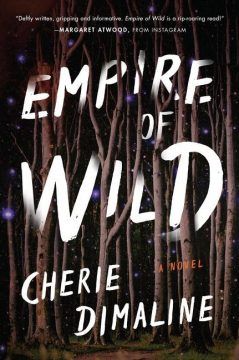

Roanhorse said she started out writing “Tolkien knockoffs about white farm boys going on journeys” because she figured that’s what epic fantasy was supposed to be. After deciding to feature a Native woman as the hero, in 2018 she released “

Roanhorse said she started out writing “Tolkien knockoffs about white farm boys going on journeys” because she figured that’s what epic fantasy was supposed to be. After deciding to feature a Native woman as the hero, in 2018 she released “ Uncoupling healthcare assets from healthcare services: Using technology and next-generation logistics, many healthcare services will be uncoupled from their facility-based operations. The explosion of telemedicine over the past 60 days, substituting for the legacy in-person physician visit, points to a future in which the home is the optimal site of medical care.

Uncoupling healthcare assets from healthcare services: Using technology and next-generation logistics, many healthcare services will be uncoupled from their facility-based operations. The explosion of telemedicine over the past 60 days, substituting for the legacy in-person physician visit, points to a future in which the home is the optimal site of medical care. Routinely hailed as one of the most

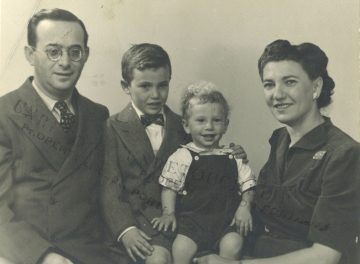

Routinely hailed as one of the most  My parents were married at six o’clock on Sunday evening, October 25, 1936, at the Quincy Manor in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, and a week or so later, they began clipping coupons from the front page of The New York Post, one coupon a day, and mailing them to the Post, twenty-four coupons at a time, which coupons, along with ninety-three cents, brought them four volumes of a twenty-volume set of The Complete Works of Charles Dickens, a set that, with full-page illustrations, was printed from plates Harper & Brothers had used for older, more expensive sets. The Post’s promotion began in January 1936 and expired on May 16, 1938, two weeks before I was born. And when, eighty-two years later, in the week of June 9, 2020—a week that marked the 150th anniversary of Dickens’s death—I was isolated in my New York City apartment due to the Covid-19 lockdown, it occurred to me that this might be a good time to do what I’d often thought of doing: reread all of Dickens.

My parents were married at six o’clock on Sunday evening, October 25, 1936, at the Quincy Manor in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, and a week or so later, they began clipping coupons from the front page of The New York Post, one coupon a day, and mailing them to the Post, twenty-four coupons at a time, which coupons, along with ninety-three cents, brought them four volumes of a twenty-volume set of The Complete Works of Charles Dickens, a set that, with full-page illustrations, was printed from plates Harper & Brothers had used for older, more expensive sets. The Post’s promotion began in January 1936 and expired on May 16, 1938, two weeks before I was born. And when, eighty-two years later, in the week of June 9, 2020—a week that marked the 150th anniversary of Dickens’s death—I was isolated in my New York City apartment due to the Covid-19 lockdown, it occurred to me that this might be a good time to do what I’d often thought of doing: reread all of Dickens. In our latest study, published in

In our latest study, published in  This August India celebrates seventy-three years as an independent nation. During these decades of independence, the country has been run democratically (aside from the twenty-one months of the infamous Emergency from 1975 to 1977). With the exception of Costa Rica, no other developing country has enjoyed as long a democratic run since World War II. And in the case of Costa Rica, it is worth bearing in mind that the country is small, with a GDP per capita

This August India celebrates seventy-three years as an independent nation. During these decades of independence, the country has been run democratically (aside from the twenty-one months of the infamous Emergency from 1975 to 1977). With the exception of Costa Rica, no other developing country has enjoyed as long a democratic run since World War II. And in the case of Costa Rica, it is worth bearing in mind that the country is small, with a GDP per capita

Here’s something I thought I’d never say: Donald Trump was correct. Back in 1997, anyway. About shaking hands. “The Japanese have it right,” the allegedly germaphobic Trump wrote (with co-author Kate Bohner) in the book Trump: The Art of the Comeback. “They stand slightly apart and do a quick, formal and very beautiful bow in order to acknowledge each other’s presence … I wish we would develop a similar greeting custom in America. In fact, I’ve often thought of taking out a series of newspaper ads encouraging the abolishment of the handshake.” Of course, because of COVID-19, the handshake is out. Unfortunately, it could make its own comeback without vigorous lobbying against it. I will now do some of that lobbying. “Recent medical reports,” Trump also wrote, “have come out saying that colds and various other ailments are spread through the act of shaking hands. I have no doubt about this.” Indeed, a search using the terms “handshake” and “infection” in journal articles between 1990 and 1997 turns up a 1991 write-up in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology with the title “Potential Role of Hands in the Spread of Respiratory Viral Infections: Studies with Human Parainfluenza Virus 3 and Rhinovirus 14.”

Here’s something I thought I’d never say: Donald Trump was correct. Back in 1997, anyway. About shaking hands. “The Japanese have it right,” the allegedly germaphobic Trump wrote (with co-author Kate Bohner) in the book Trump: The Art of the Comeback. “They stand slightly apart and do a quick, formal and very beautiful bow in order to acknowledge each other’s presence … I wish we would develop a similar greeting custom in America. In fact, I’ve often thought of taking out a series of newspaper ads encouraging the abolishment of the handshake.” Of course, because of COVID-19, the handshake is out. Unfortunately, it could make its own comeback without vigorous lobbying against it. I will now do some of that lobbying. “Recent medical reports,” Trump also wrote, “have come out saying that colds and various other ailments are spread through the act of shaking hands. I have no doubt about this.” Indeed, a search using the terms “handshake” and “infection” in journal articles between 1990 and 1997 turns up a 1991 write-up in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology with the title “Potential Role of Hands in the Spread of Respiratory Viral Infections: Studies with Human Parainfluenza Virus 3 and Rhinovirus 14.” A woman stands in an otherworldly landscape, looking out. The landscape is sublime, though not the European sublime of cliffs, peaks, and mist. Here the sublime is

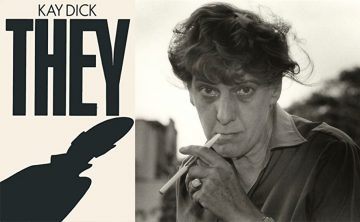

A woman stands in an otherworldly landscape, looking out. The landscape is sublime, though not the European sublime of cliffs, peaks, and mist. Here the sublime is  It’s apt then that much of the novel’s power lies in its mystery. The narrator—if, indeed, we’re listening to the same single voice throughout—seems to be a writer, who lives in a book-filled ex-coastguard’s cottage, alone apart from their dog. They are never named. Nor is his or her gender revealed, something that’s in line with what Kris Kirk, in an interview with Dick in the Guardian in 1984 described as Dick’s “androgynous mental attitude.” Dick had just finished explaining why the “overall tone” of the personal relationships depicted in her books is always bisexual, which is how she herself identified. She also notes that although she’s sexually attracted to both men and women, there’s “something extra” in her relationships with the latter; “this love, this emotion,” she clarifies. “I have certain prejudices and one of them is that I cannot bear apartheid of any kind—class, colour or sex,” she tells Kirk. “Gender is of no bloody account and if anything drives me round the bend it’s these separatist feminist lessies.” Given that Dick made a habit of loosely fictionalizing her own experiences, I’ve come to think of her protagonist in They as female. Even more inscrutable though are the “they” of the book’s title; “omnipresent and elusive,” as Howard describes them, extremely dangerous and violent, but also strangely vacant and automaton-like. “They” are rarely distinguished as individuals, which situates them in stark contrast to the narrator and her acquaintances.

It’s apt then that much of the novel’s power lies in its mystery. The narrator—if, indeed, we’re listening to the same single voice throughout—seems to be a writer, who lives in a book-filled ex-coastguard’s cottage, alone apart from their dog. They are never named. Nor is his or her gender revealed, something that’s in line with what Kris Kirk, in an interview with Dick in the Guardian in 1984 described as Dick’s “androgynous mental attitude.” Dick had just finished explaining why the “overall tone” of the personal relationships depicted in her books is always bisexual, which is how she herself identified. She also notes that although she’s sexually attracted to both men and women, there’s “something extra” in her relationships with the latter; “this love, this emotion,” she clarifies. “I have certain prejudices and one of them is that I cannot bear apartheid of any kind—class, colour or sex,” she tells Kirk. “Gender is of no bloody account and if anything drives me round the bend it’s these separatist feminist lessies.” Given that Dick made a habit of loosely fictionalizing her own experiences, I’ve come to think of her protagonist in They as female. Even more inscrutable though are the “they” of the book’s title; “omnipresent and elusive,” as Howard describes them, extremely dangerous and violent, but also strangely vacant and automaton-like. “They” are rarely distinguished as individuals, which situates them in stark contrast to the narrator and her acquaintances. If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” So said

If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” So said