Dorothy Bishop in Nature:

The past decade has seen a raft of efforts to encourage robust, credible research. Some focus on changing incentives, for example by modifying promotion and publication criteria to favour open science over sensational breakthroughs. But attention also needs to be paid to individuals. All-too-human cognitive biases can lead us to see results that aren’t there. Faulty reasoning results in shoddy science, even when the intentions are good.

The past decade has seen a raft of efforts to encourage robust, credible research. Some focus on changing incentives, for example by modifying promotion and publication criteria to favour open science over sensational breakthroughs. But attention also needs to be paid to individuals. All-too-human cognitive biases can lead us to see results that aren’t there. Faulty reasoning results in shoddy science, even when the intentions are good.

Researchers need to become more aware of these pitfalls. Just as lab scientists are not allowed to handle dangerous substances without safety training, researchers should not be allowed anywhere near a P value or similar measure of statistical probability until they have demonstrated that they understand what it means.

We all tend to overlook evidence that contradicts our views. When confronted with new data, our pre-existing ideas can cause us to see structure that isn’t there. This is a form of confirmation bias, whereby we look for and recall information that fits with what we already think. It can be adaptive: humans need to be able to separate out important information and act quickly to get out of danger. But this filtering can lead to scientific error.

Physicist Robert Millikan’s 1913 measurement of the charge on the electron is one example.

More here.

NOAM: For me it’s been extremely busy. I’m isolated, don’t go out, and don’t have any visitors. Constantly occupied with interviews, requests way beyond what I can accept. Busier than I can ever remember.

NOAM: For me it’s been extremely busy. I’m isolated, don’t go out, and don’t have any visitors. Constantly occupied with interviews, requests way beyond what I can accept. Busier than I can ever remember. But the Magdalena has also been a place of unimaginable violence, death and environmental destruction. Colombia’s modern history, recounted here in episodic vignettes, appears to be one drawn-out conflict, from the bloodletting of the conquistadors, to the War of Independence and the multiple civil wars that followed, to a post-Second World War era known as La Violencia, which pitted liberals against conservatives in a brutal struggle for power.

But the Magdalena has also been a place of unimaginable violence, death and environmental destruction. Colombia’s modern history, recounted here in episodic vignettes, appears to be one drawn-out conflict, from the bloodletting of the conquistadors, to the War of Independence and the multiple civil wars that followed, to a post-Second World War era known as La Violencia, which pitted liberals against conservatives in a brutal struggle for power. The clichés of romantic ballads can be a comforting reprieve from the coldness of the world. Pop ballads are fugue states of feeling, offering reams of experience in three minutes or less. Leon Russell’s “A Song for You,” is the ultimate alternate-universe lament, as if Russell translated the multiverse theory from the jargon of physics into lyrics. Semi-unofficially, Wikipedia says “A Song For You” has been covered over 217 times, on studio albums, live recordings, tours, and American Idol stages. It’s been recorded by musicians as diverse as Donny Hathaway, Aretha Franklin, Beyoncé, Bizzy Bone, Amy Winehouse, Justin Vernon of Bon Iver, and Indiana Pacers star Victor Oladipo. Seriously unofficially, the song has been covered thousands more times, interpolated, sampled, and strummed at cafés, quoted in marriage vows, hummed at memorials, two-stepped to at ‘70s spring dances, and poignantly blared in two-person car concerts. Like every great ballad, the song’s lyrics lend themselves to an easy expression of intimacy. “A Song for You” is as blank-slate heart-rending as any song that’s been dedicated to a lover on a radio station’s dedication hour, when the lyrics are cherry-picked to pluck at heart-strings.

The clichés of romantic ballads can be a comforting reprieve from the coldness of the world. Pop ballads are fugue states of feeling, offering reams of experience in three minutes or less. Leon Russell’s “A Song for You,” is the ultimate alternate-universe lament, as if Russell translated the multiverse theory from the jargon of physics into lyrics. Semi-unofficially, Wikipedia says “A Song For You” has been covered over 217 times, on studio albums, live recordings, tours, and American Idol stages. It’s been recorded by musicians as diverse as Donny Hathaway, Aretha Franklin, Beyoncé, Bizzy Bone, Amy Winehouse, Justin Vernon of Bon Iver, and Indiana Pacers star Victor Oladipo. Seriously unofficially, the song has been covered thousands more times, interpolated, sampled, and strummed at cafés, quoted in marriage vows, hummed at memorials, two-stepped to at ‘70s spring dances, and poignantly blared in two-person car concerts. Like every great ballad, the song’s lyrics lend themselves to an easy expression of intimacy. “A Song for You” is as blank-slate heart-rending as any song that’s been dedicated to a lover on a radio station’s dedication hour, when the lyrics are cherry-picked to pluck at heart-strings. Yale physicists have developed an error-correcting cat—a new device that combines the Schrödinger’s cat concept of superposition (a physical system existing in two states at once) with the ability to fix some of the trickiest errors in a quantum computation. It is Yale’s latest breakthrough in the effort to master and manipulate the physics necessary for a useful quantum computer: Correcting the stream of errors that crop up among fragile bits of quantum

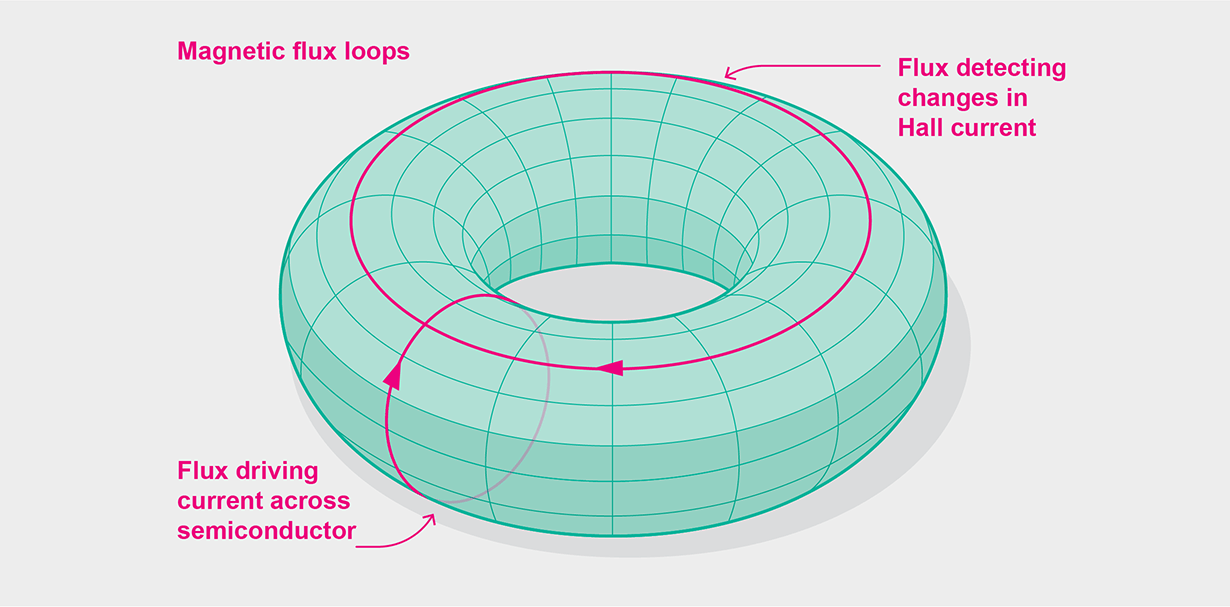

Yale physicists have developed an error-correcting cat—a new device that combines the Schrödinger’s cat concept of superposition (a physical system existing in two states at once) with the ability to fix some of the trickiest errors in a quantum computation. It is Yale’s latest breakthrough in the effort to master and manipulate the physics necessary for a useful quantum computer: Correcting the stream of errors that crop up among fragile bits of quantum  The far left of the Democratic Party spent much of the primary attacking Kamala Harris, decrying her as an

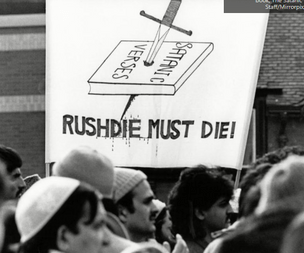

The far left of the Democratic Party spent much of the primary attacking Kamala Harris, decrying her as an  His work was substantial, his opinions horrendous, his reputation a battleground. It was February 1949 and the Fellows in American Letters of the Library of Congress had decided to award the inaugural Bollingen Prize for Poetry to Ezra Pound for The Pisan Cantos. Pound, a giant of modernism, had begun the poems in a US Army detention camp and finished them in a psychiatric hospital under indictment for treason, having spent much of the war broadcasting anti-Semitic, fascist propaganda for Mussolini. The judging panel, which included W. H. Auden, Robert Lowell and Pound’s friend T. S. Eliot, justified its decision on purely aesthetic grounds, because to take into account Pound’s politics

His work was substantial, his opinions horrendous, his reputation a battleground. It was February 1949 and the Fellows in American Letters of the Library of Congress had decided to award the inaugural Bollingen Prize for Poetry to Ezra Pound for The Pisan Cantos. Pound, a giant of modernism, had begun the poems in a US Army detention camp and finished them in a psychiatric hospital under indictment for treason, having spent much of the war broadcasting anti-Semitic, fascist propaganda for Mussolini. The judging panel, which included W. H. Auden, Robert Lowell and Pound’s friend T. S. Eliot, justified its decision on purely aesthetic grounds, because to take into account Pound’s politics  It all began with a simple question.

It all began with a simple question. Six to eight weeks. That’s how long some of the nation’s leading public health experts say it would take to finally get the United States’ coronavirus epidemic under control. If the country were to take the right steps, many thousands of people could be spared from the ravages of Covid-19. The economy could finally begin to repair itself, and Americans could start to enjoy something more like normal life.

Six to eight weeks. That’s how long some of the nation’s leading public health experts say it would take to finally get the United States’ coronavirus epidemic under control. If the country were to take the right steps, many thousands of people could be spared from the ravages of Covid-19. The economy could finally begin to repair itself, and Americans could start to enjoy something more like normal life. Eileen Blair, George Orwell’s first wife, is the subject of this welcome and assiduously researched biography by Sylvia Topp. Eileen married Orwell in 1936 when he was a virtual unknown and, until her death in 1945 at the age of just thirty-nine, shared with him a life that was lived primarily on the unreliable income from his writing. She did not live to see even the beginnings of the worldwide fame that would come her husband’s way with Animal Farm, which was published in the year of her death.

Eileen Blair, George Orwell’s first wife, is the subject of this welcome and assiduously researched biography by Sylvia Topp. Eileen married Orwell in 1936 when he was a virtual unknown and, until her death in 1945 at the age of just thirty-nine, shared with him a life that was lived primarily on the unreliable income from his writing. She did not live to see even the beginnings of the worldwide fame that would come her husband’s way with Animal Farm, which was published in the year of her death. Immediately afterwards, the paintings take a turn towards our grosser world, and the realism begins to hurt. The portrait of John Minton has a piercing sadness. The portrait of Francis Bacon with lowered eyes has a Germanic intensity; it’s as if Grunewald had started a noli me tangere. The wide-eyed girl appears once more, in a green dressing gown, with a dog resting its head in her lap, but she has come back to our edgy, nerve-ridden world. Another girl appears. She has yellow hair and a charming face, and the images of her are still controlled by line.

Immediately afterwards, the paintings take a turn towards our grosser world, and the realism begins to hurt. The portrait of John Minton has a piercing sadness. The portrait of Francis Bacon with lowered eyes has a Germanic intensity; it’s as if Grunewald had started a noli me tangere. The wide-eyed girl appears once more, in a green dressing gown, with a dog resting its head in her lap, but she has come back to our edgy, nerve-ridden world. Another girl appears. She has yellow hair and a charming face, and the images of her are still controlled by line. We are used to thinking of idleness as a vice, something to be ashamed of. But when the British philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote “

We are used to thinking of idleness as a vice, something to be ashamed of. But when the British philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote “ What is

What is  When it comes to many philosophical issues, people feel conflicted or confused. There is something drawing them toward one intuition but also something drawing them toward the exact opposite intuition. This tension seems to be an important aspect of what makes us regard these issues as important philosophical problems in the first place.

When it comes to many philosophical issues, people feel conflicted or confused. There is something drawing them toward one intuition but also something drawing them toward the exact opposite intuition. This tension seems to be an important aspect of what makes us regard these issues as important philosophical problems in the first place.