Laurent Dubreuil in Harper’s Magazine:

In August 2017, a few weeks before the fall semester began at Cornell University, I received an email inviting me to participate in a campaign called “I’m First!” The idea was to encourage “faculty and staff on campus to identify themselves, via T-shirt or button, as the first in their family to graduate from a four-year institution.” The rationale for this themed costume party was the following: “This visual campaign will allow first-generation students to clearly identify (and connect with) faculty and professional staff that have had similar experiences as them!” Though I have been a tenured professor at Cornell for eleven years, neither of my parents, who are French, pursued post-secondary education. My father finished high school; my mother learned stenography at a vocational school and got her first job at sixteen. I guess this made me an ideal candidate to wear the nice T-shirt provided by the administration. But I declined. I’m not ashamed of my background, and I don’t underestimate the challenges students face when they are the first in their family to attend college. But the two occurrences of the verb “to identify” in one eight-line paragraph were clear hints that the I’m First! initiative—part of a national campaign—was pushing a new social identity: “first-gen.”

In August 2017, a few weeks before the fall semester began at Cornell University, I received an email inviting me to participate in a campaign called “I’m First!” The idea was to encourage “faculty and staff on campus to identify themselves, via T-shirt or button, as the first in their family to graduate from a four-year institution.” The rationale for this themed costume party was the following: “This visual campaign will allow first-generation students to clearly identify (and connect with) faculty and professional staff that have had similar experiences as them!” Though I have been a tenured professor at Cornell for eleven years, neither of my parents, who are French, pursued post-secondary education. My father finished high school; my mother learned stenography at a vocational school and got her first job at sixteen. I guess this made me an ideal candidate to wear the nice T-shirt provided by the administration. But I declined. I’m not ashamed of my background, and I don’t underestimate the challenges students face when they are the first in their family to attend college. But the two occurrences of the verb “to identify” in one eight-line paragraph were clear hints that the I’m First! initiative—part of a national campaign—was pushing a new social identity: “first-gen.”

More here.

A team of mathematicians has finally finished off Keller’s conjecture, but not by working it out themselves. Instead, they taught a fleet of computers to do it for them.

A team of mathematicians has finally finished off Keller’s conjecture, but not by working it out themselves. Instead, they taught a fleet of computers to do it for them. At first, it’s hard to fathom how a public restroom with transparent walls could possibly help ease toilet anxiety — but a counterintuitive design by one of Japan’s most innovative architects aims to do just that.

At first, it’s hard to fathom how a public restroom with transparent walls could possibly help ease toilet anxiety — but a counterintuitive design by one of Japan’s most innovative architects aims to do just that. FEBRUARY WAS ONLY six months ago, but it belongs to a different era. Back then I still thought that, notwith-standing different private interests, moral values, and group allegiances, the United States could still function as a democratic society. I remember I was visiting Amherst College to take part in a public conversation with the novelist Susan Choi on the art of fiction. After the event, we signed books, shook hands with attendees, and went to dinner with our hosts in a packed restaurant. The next morning, I took a walk around the campus, ending up at the local bookstore, where I picked up and put down a dozen different novels before settling on one. Phrases like “aerosolized droplets” and “surface contamination” had not yet entered my daily vocabulary.

FEBRUARY WAS ONLY six months ago, but it belongs to a different era. Back then I still thought that, notwith-standing different private interests, moral values, and group allegiances, the United States could still function as a democratic society. I remember I was visiting Amherst College to take part in a public conversation with the novelist Susan Choi on the art of fiction. After the event, we signed books, shook hands with attendees, and went to dinner with our hosts in a packed restaurant. The next morning, I took a walk around the campus, ending up at the local bookstore, where I picked up and put down a dozen different novels before settling on one. Phrases like “aerosolized droplets” and “surface contamination” had not yet entered my daily vocabulary. What are we to do with Ezra Pound? One answer would be to “cancel” him, to dump his statue in some river and let the water erase it. This wouldn’t be without cause: calling his politics and personality repugnant is an understatement. But it would also be too simple. Pound’s fingerprints are everywhere: most famously on The Waste Land, but also on the careers of Yeats, Frost, William Carlos Williams, and H. D. (Hilda Doolittle); on the publication of Joyce’s Ulysses; on Imagism, Vorticism, and the “New Poetry” that emerged in Poetry a century ago. He was, inescapably, one of the pivotal figures of twentieth-century literature. If we have to live with Pound, the necessary question is how: merely as a player in literary history or also as the author of literature still worth reading?

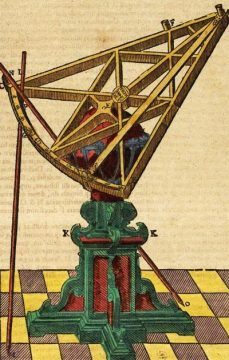

What are we to do with Ezra Pound? One answer would be to “cancel” him, to dump his statue in some river and let the water erase it. This wouldn’t be without cause: calling his politics and personality repugnant is an understatement. But it would also be too simple. Pound’s fingerprints are everywhere: most famously on The Waste Land, but also on the careers of Yeats, Frost, William Carlos Williams, and H. D. (Hilda Doolittle); on the publication of Joyce’s Ulysses; on Imagism, Vorticism, and the “New Poetry” that emerged in Poetry a century ago. He was, inescapably, one of the pivotal figures of twentieth-century literature. If we have to live with Pound, the necessary question is how: merely as a player in literary history or also as the author of literature still worth reading? One of the underappreciated keys to launching the scientific age was the work of Tycho Brahe. His contribution was simple but revolutionary: At a point just before the invention of the telescope, he wanted to precisely record the positions of the planets and the stars. However, the instruments used before him to make these measurements produced unreliable results. Brahe was a Danish nobleman, and thus deemed to be above such pursuits as astronomy. But as a nobleman, he had the financial means of only a very few. He cast aside convention to spend a lifetime making better instruments to take these more precise measurements of the stars and planets, and then used those instruments to make measurements far superior to any that had been previously made. It was this revolutionary work that allowed his student Johannes Kepler to come up with his three laws of planetary motion. And it was Kepler’s work that was so helpful to Sir Isaac Newton and his laws of thermodynamics.

One of the underappreciated keys to launching the scientific age was the work of Tycho Brahe. His contribution was simple but revolutionary: At a point just before the invention of the telescope, he wanted to precisely record the positions of the planets and the stars. However, the instruments used before him to make these measurements produced unreliable results. Brahe was a Danish nobleman, and thus deemed to be above such pursuits as astronomy. But as a nobleman, he had the financial means of only a very few. He cast aside convention to spend a lifetime making better instruments to take these more precise measurements of the stars and planets, and then used those instruments to make measurements far superior to any that had been previously made. It was this revolutionary work that allowed his student Johannes Kepler to come up with his three laws of planetary motion. And it was Kepler’s work that was so helpful to Sir Isaac Newton and his laws of thermodynamics.

When Don Lyons, director of the Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program visited a small inland valley in Japan, he found a local variety of rice colloquially called “cormorant rice.” The grain got its moniker not from its size or color or area of origin, but from the

When Don Lyons, director of the Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program visited a small inland valley in Japan, he found a local variety of rice colloquially called “cormorant rice.” The grain got its moniker not from its size or color or area of origin, but from the

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, a

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, a  Elena Ferrante

Elena Ferrante Nearly 60 years ago, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Eugene Wigner captured one of the many oddities of quantum mechanics in a thought experiment. He imagined a friend of his, sealed in a lab, measuring a particle such as an atom while Wigner stood outside. Quantum mechanics famously allows particles to occupy many locations at once—a so-called superposition—but the friend’s observation “collapses” the particle to just one spot. Yet for Wigner, the superposition remains: The collapse occurs only when he makes a measurement sometime later. Worse, Wigner also sees the friend in a superposition. Their experiences directly conflict.

Nearly 60 years ago, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Eugene Wigner captured one of the many oddities of quantum mechanics in a thought experiment. He imagined a friend of his, sealed in a lab, measuring a particle such as an atom while Wigner stood outside. Quantum mechanics famously allows particles to occupy many locations at once—a so-called superposition—but the friend’s observation “collapses” the particle to just one spot. Yet for Wigner, the superposition remains: The collapse occurs only when he makes a measurement sometime later. Worse, Wigner also sees the friend in a superposition. Their experiences directly conflict. IN 1953, ISAIAH BERLIN published his long essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” outlining his now-famous Oxbridge variant on there are two kinds of people in this world. He drew the title from an ambiguous fragment attributed to the ancient lyric poet Archilochus of Paros: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” Written with the aim of pointing out tensions between Tolstoy’s grand view of history and the artistic temperament that saw such a view as untenable, Berlin’s essay became an unlikely hit, although less for its argument about Russian literature than for its contention that two antithetical personae govern the world of ideas: hedgehogs, who view the world in terms of some all-embracing system, seeing all facts as fitting into a grand pattern; and foxes, those pluralists or particularists who refuse “big theory” for reasons either intellectual or temperamental.

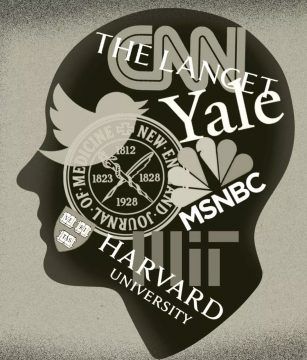

IN 1953, ISAIAH BERLIN published his long essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” outlining his now-famous Oxbridge variant on there are two kinds of people in this world. He drew the title from an ambiguous fragment attributed to the ancient lyric poet Archilochus of Paros: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” Written with the aim of pointing out tensions between Tolstoy’s grand view of history and the artistic temperament that saw such a view as untenable, Berlin’s essay became an unlikely hit, although less for its argument about Russian literature than for its contention that two antithetical personae govern the world of ideas: hedgehogs, who view the world in terms of some all-embracing system, seeing all facts as fitting into a grand pattern; and foxes, those pluralists or particularists who refuse “big theory” for reasons either intellectual or temperamental. Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups.

Physicists have traditionally simplified systems as much as possible, in order to shed light on fundamental properties. But small, simple parts build up into large, complex wholes. Are there new rules and laws of nature that apply specifically to the realm of complexity? This has been a popular question for a few decades now, and we have some answers but not as many as we would like. Neil Johnson is an expert on complex systems generally, and information networks in particular. We discuss how self-organization can arise from individual units following their own agendas, and how we can mathematically characterize such behavior. Then we talk about information networks in the modern world, including how they have been used to spread disinformation and find recruits for radical fringe groups. A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of

A first-hand account of Britain’s role in the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected prime minister of