Category: Recommended Reading

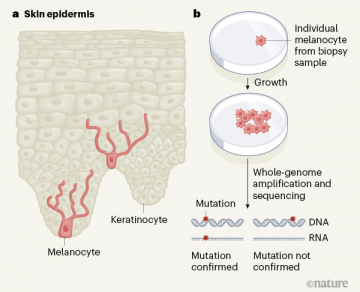

Seeds of cancer in normal skin

Inigo Martincorena in Nature:

Mutations occur in our cells throughout life. Although most mutations are harmless, they accumulate in number in our tissues as we age, and if they arise in key genes, they can alter cellular behaviour and set cells on a path towards cancer. There is also speculation that somatic mutations (those in non-reproductive tissues) might contribute to ageing and to diseases unrelated to cancer. However, technical difficulties in detecting the mutations present in a small number of cells, or even in single cells, have hampered research and limited progress in understanding the first steps in cancer development and the impact of somatic mutation on ageing and disease. Writing in Nature, Tang et al.1 report work that overcame some of these experimental limitations to explore somatic mutations and selection in individual melanocytes — the type of skin cell that can give rise to the cancer melanoma.

Mutations occur in our cells throughout life. Although most mutations are harmless, they accumulate in number in our tissues as we age, and if they arise in key genes, they can alter cellular behaviour and set cells on a path towards cancer. There is also speculation that somatic mutations (those in non-reproductive tissues) might contribute to ageing and to diseases unrelated to cancer. However, technical difficulties in detecting the mutations present in a small number of cells, or even in single cells, have hampered research and limited progress in understanding the first steps in cancer development and the impact of somatic mutation on ageing and disease. Writing in Nature, Tang et al.1 report work that overcame some of these experimental limitations to explore somatic mutations and selection in individual melanocytes — the type of skin cell that can give rise to the cancer melanoma.

The epidermis is the skin’s outermost layer. Just 0.1 millimetres thick, the epidermis is battered by mutation-promoting ultraviolet rays over a person’s lifetime, and is the origin of the vast majority of skin cancers.

To understand the extent of somatic mutation in a human tissue, and the origin of skin cancers, a previous study2 used DNA sequencing of small biopsies of normal epidermis. This revealed not only that mutations are common in normal cells, but also that mutations in cancer-promoting genes favour the growth of small groups of mutant cells (clones) that progressively colonize our skin as we age. However, the sequencing of biopsies of epidermis made up of thousands of cells mostly detected mutations in cells called keratinocytes, which comprise around 90% of all cells in the epidermis3. These are the cells from which the common, but typically treatable, non-melanoma skin cancers develop. The origins of melanoma, a rarer but more lethal form of skin cancer, lie in single cells scattered throughout the skin, called melanocytes (Fig. 1). These cells produce a pigment called melanin that gives skin its colour and protects it from the onslaught of sun damage.

More here.

The Language of Pain

Cristina Rivera Garza in The Paris Review:

On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places.

On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places.

It is difficult, of course, to write about these things. In fact, the very reason acts like these are carried out is so that they render us speechless. Their ultimate objective is to use horror to paralyze completely—an offense committed not only against human life but also, above all, against the human condition.

In Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence—an indispensable book for thinking through this reality, as understanding it is almost impossible—Adriana Cavarero reminds us that terror manifests when the body trembles and flees in order to survive. The terrorized body experiences fear and, upon finding itself within fear’s grasp, attempts to escape it. Meanwhile, horror, taken from the Latin verb horrere, goes far beyond the fear that so frequently alerts us to danger or threatens to transcend it. Confronted with Medusa’s decapitated head, a body destroyed beyond human recognition, the horrified part their lips and, incapable of uttering a single word, incapable of articulating the disarticulation that fills their gaze, mouth wordlessly. Horror is intrinsically linked to repugnance, Cavarero argues. Bewildered and immobile, the horrified are stripped of their agency, frozen in a scene of everlasting marble statues. They stare, and even though they stare fixedly, or perhaps precisely because they stare fixedly, they cannot do anything. More than vulnerable—a condition we all experience—they are defenseless. More than fragile, they are helpless. As such, horror is, above all, a spectacle—the most extreme spectacle of power.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

“When a woman, having placed one of her feet on the foot of her lover, and the other on one of his thighs, passes one of her arms round his back, and the other on his shoulders, makes slightly the sounds of singing and cooing, and wishes, as it were, to climb up him in order to have a kiss, it is called an embrace like the ‘climbing of a tree.’” —from The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana, tr. by Sir Richard Burton

Climbing of a Tree

Once, half way up your thigh,

my calf twisted around yours

while my hands clasped behind your ears

like the tender tendril ends

of wisteria, leaves still

furled together.

Now I am chopping these down

whole woody coils fall

each time I stop to cover my face

and cry. I feel them,

lying heavily on the ground

and dragging as I walk.

I smell them, living green,

and they coat my hands, sticky sweet.

by A. Anupama

from NC Magazine, Poetry,

Vol. VI, No. 6, June 2015

The Pre-Jazz Life and Music of Buddy Bolden

Howard Fishman at Salmagundi:

The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive.

The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive.

more here.

The Great Buddy Bolden – Buddy Bolden Blues

The Craft: How the Freemasons Made the Modern World

Darrin M McMahon at Literary Review:

The story of freemasonry is not all fraternal handshakes and matey slaps on the back, of course. Secrecy may be seductive, but it can also provoke wild speculation of a kind that didn’t end with the Portuguese Inquisition. Amid the violent upheavals of the French Revolution, the displaced Catholic priest Augustin Barruel could be heard denouncing revolutionary events as the consequence of a mischievous plot hatched by the brotherhood. Barruel provided little evidence for his claims, largely because there was none. But he did offer in his spectacularly successful book on the subject a template of supposed masonic machinations that has been recycled ever since. Dickie devotes some of his best chapters to this dark history of suspicion and persecution, with freemasons serving as scapegoats for Mussolini, Hitler and Franco, among many others. And today, freemasonry is banned everywhere in the Muslim world except Lebanon and Morocco.

The story of freemasonry is not all fraternal handshakes and matey slaps on the back, of course. Secrecy may be seductive, but it can also provoke wild speculation of a kind that didn’t end with the Portuguese Inquisition. Amid the violent upheavals of the French Revolution, the displaced Catholic priest Augustin Barruel could be heard denouncing revolutionary events as the consequence of a mischievous plot hatched by the brotherhood. Barruel provided little evidence for his claims, largely because there was none. But he did offer in his spectacularly successful book on the subject a template of supposed masonic machinations that has been recycled ever since. Dickie devotes some of his best chapters to this dark history of suspicion and persecution, with freemasons serving as scapegoats for Mussolini, Hitler and Franco, among many others. And today, freemasonry is banned everywhere in the Muslim world except Lebanon and Morocco.

more here.

Sunday, October 11, 2020

Liberalism and Its Discontents

Francis Fukuyama in American Purpose:

The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair. The democracy part refers to the accountability of those who hold political power through mechanisms like free and fair multiparty elections under universal adult franchise. The liberal part, by contrast, refers primarily to a rule of law that constrains the power of government and requires that even the most powerful actors in the system operate under the same general rules as ordinary citizens. Liberal democracies, in other words, have a constitutional system of checks and balances that limits the power of elected leaders.

The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair. The democracy part refers to the accountability of those who hold political power through mechanisms like free and fair multiparty elections under universal adult franchise. The liberal part, by contrast, refers primarily to a rule of law that constrains the power of government and requires that even the most powerful actors in the system operate under the same general rules as ordinary citizens. Liberal democracies, in other words, have a constitutional system of checks and balances that limits the power of elected leaders.

Democracy itself is being challenged by authoritarian states like Russia and China that manipulate or dispense with free and fair elections. But the more insidious threat arises from populists within existing liberal democracies who are using the legitimacy they gain through their electoral mandates to challenge or undermine liberal institutions.

More here.

What Should the U.S. Learn from South Korea’s Covid-19 Success?

Wudan Yan and Ann Babe in Undark:

The World Health Organization and American health officials have praised South Korea for its Covid-19 response. But when it comes to learning from it, many Americans seem less willing to adopt their ally’s practices.

The World Health Organization and American health officials have praised South Korea for its Covid-19 response. But when it comes to learning from it, many Americans seem less willing to adopt their ally’s practices.

Even as U.S. public health officials scramble to track infections, they have sometimes struggled to win basic cooperation from a public that prizes privacy, let alone implement the kind of widespread tracking seen in South Korea. The barriers to doing so are steep, highlighting stark differences not only between the two countries’ contact tracing infrastructures and public health systems, but also people’s civic trust and sense of public surveillance and social responsibility. Americans’ perceptions in giving up privacy for the public good have shifted before, particularly after the 9/11 attacks. But if the U.S. could overcome such hurdles and adopt South Korea’s containment strategy, would it even be desirable?

More here.

The Eternal Marx

Yanis Varoufakis in Project Syndicate:

The problem with egotists is that they are not particularly good at being selfish. They can accumulate wealth, legal rights, and power, but, in the end, they are pitiable figures who cannot know fulfillment. This assessment of the “egotistic man,” whom he defines as “an individual withdrawn behind his private interests and whim and separated from the community,” is the gravamen of Karl Marx’s critique of possessive individualism – the moral philosophy underpinning capitalism’s oeuvre.

As I read Shlomo Avineri’s exquisite recent biography of Marx, I became increasingly troubled by the image of an individual “separated from the community.” But the individual I was thinking about was Marx himself: the wandering revolutionary who, expelled from his native Germany and forced to leave Brussels and Paris, died, stateless, in liberal Victorian England. Suddenly, an inconvenient question occurred to me.

Why did I always find Shakespeare’s presentation of Shylock and Caliban particularly objectionable (in The Merchant of Venice and The Tempest, respectively)? Was it merely the identification of nastiness with a Jewish entrepreneur and a black man?

No, there was more to it.

More here.

Mohammad Reza Shajarian (1940 – 2020)

Johnny Nash (1940 – 2020)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NkwJ-g0iJ6w&ab_channel=Josegeraldofonseca

Eddie Van Halen (1955 – 2020)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RLsEvZgmRVA&ab_channel=AndrewWilliamWright

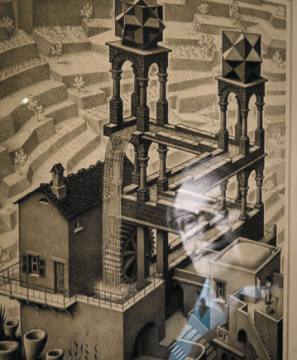

Roger Penrose and the vision thing

Philip Ball in Prospect Magazine:

Penrose—who has now won the Nobel—is still defining the way we see the universe. But, asked Philip Ball in 2017, in today’s world of ultra-specialised science, could a thinker of such breadth ever emerge again?

Penrose hails from one of the great intellectual dynasties of the 20th century. His father Lionel was a distinguished psychiatrist and geneticist, his uncle was the surrealist artist Roland Penrose. Roger was one of four children; older brother Oliver became a theoretical physicist, younger brother Jonathan was British chess champion a record-breaking 10 times, and sister Shirley Hodgson is a professor of cancer genetics.

Penrose hails from one of the great intellectual dynasties of the 20th century. His father Lionel was a distinguished psychiatrist and geneticist, his uncle was the surrealist artist Roland Penrose. Roger was one of four children; older brother Oliver became a theoretical physicist, younger brother Jonathan was British chess champion a record-breaking 10 times, and sister Shirley Hodgson is a professor of cancer genetics.

In this house there was no escaping mathematics. “I used to make polyhedra with my father,” Penrose told me. “There were no clear lines between games and toys for children and his professional work.” That, needless to say, may have been a mixed blessing: “He wasn’t very good at relating to us in an emotional way—it was all about science and mathematics.”

But if number games substituted for play in the Penrose home, one happy result may have been an almost playful quality of his approach to mathematics. His thinking is animated by a phenomenal visual sense of geometry. The sheer power of his mind’s eye is, his peer Martin Rees, the current Astronomer Royal, suggested to me, his defining characteristic. In all of Penrose’s books, abstruse theories are illuminated by pictorial representations. He puts this visual sensibility down to his father, but his grandfather James Doyle Penrose was, like his uncle Ronald, a professional artist. In Roger, this ability manifests itself in an intuition of complex spatial relationships, which gave him an affinity for the Dutch artist MC Escher. While a graduate student, Penrose saw “an exhibition in the Van Gogh Museum by this artist I’d never heard of. I was quite blown over. I came away and drew pictures of bridges and roads, which gradually simplified into the tribar.” This is the optical illusion of an “impossible triangle,” the corners of which make sense spatially on their own but not together.

More here.

Why Are We in the West So Weird? A Theory

Daniel C. Dennett in The New York Times:

According to copies of copies of fragments of ancient texts, Pythagoras in about 500 B.C. exhorted his followers: Don’t eat beans! Why he issued this prohibition is anybody’s guess (Aristotle thought he knew), but it doesn’t much matter because the idea never caught on. According to Joseph Henrich, some unknown early church fathers about a thousand years later promulgated the edict: Don’t marry your cousin! Why they did this is also unclear, but if Henrich is right — and he develops a fascinating case brimming with evidence — this prohibition changed the face of the world, by eventually creating societies and people that were WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic. In the argument put forward in this engagingly written, excellently organized and meticulously argued book, this simple rule triggered a cascade of changes, creating states to replace tribes, science to replace lore and law to replace custom. If you are reading this you are very probably WEIRD, and so are almost all of your friends and associates, but we are outliers on many psychological measures.

According to copies of copies of fragments of ancient texts, Pythagoras in about 500 B.C. exhorted his followers: Don’t eat beans! Why he issued this prohibition is anybody’s guess (Aristotle thought he knew), but it doesn’t much matter because the idea never caught on. According to Joseph Henrich, some unknown early church fathers about a thousand years later promulgated the edict: Don’t marry your cousin! Why they did this is also unclear, but if Henrich is right — and he develops a fascinating case brimming with evidence — this prohibition changed the face of the world, by eventually creating societies and people that were WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic. In the argument put forward in this engagingly written, excellently organized and meticulously argued book, this simple rule triggered a cascade of changes, creating states to replace tribes, science to replace lore and law to replace custom. If you are reading this you are very probably WEIRD, and so are almost all of your friends and associates, but we are outliers on many psychological measures.

The world today has billions of inhabitants who have minds strikingly different from ours. Roughly, we weirdos are individualistic, think analytically, believe in free will, take personal responsibility, feel guilt when we misbehave and think nepotism is to be vigorously discouraged, if not outlawed. Right? They (the non-WEIRD majority) identify more strongly with family, tribe, clan and ethnic group, think more “holistically,” take responsibility for what their group does (and publicly punish those who besmirch the group’s honor), feel shame — not guilt — when they misbehave and think nepotism is a natural duty.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Geneology

Outside, it’s cold like the day

my father’s grandpa drowned

while Sigrid salted cod on walls

of stacked antlers. Their sons

and daughter fled to Eden

Prairie. One, my father’s uncle, lost

a claim in Manitoba, another crashed

a Hupmobile. One died ice-fishing.

My father’s mother, pink and vicious, made

him cover the bidet with plywood

when we lived in Tehran. Made me drive

all over Fairfax County in search

of Carnival glass. Told me “Never

marry a woman for her looks.” My mother’s

dad lost his lungs to mustard gas. Her mom

never gambled. Betty lived in Hollywood

working at the studios, roller-skating

with a man who would later play

Tonto. She rented a room

in a house with a victory garden until

the Tamuras were shipped

to Utah, then married Dad, who left

to kill Koreans. On the shipto Japan to join him in Kobe, my sister

scared me with stories of dwarves. My children’s

mom is small and pale, like the pages

of an appointment book, except when speaking

Spanish. Then, her hands become larakeets, her eyes

marcasite. Her grandfather knew the Franks

before they moved to Holland, and he

to Pasadena, where he never met

my mother who skis like she’s waltzing,

or my father, who came home and built

a barbeque of brick, or my sister the shrink,

or my brother who sells drugs, or my other sister

for that matter. They all live

in California and no one

ever dies. There’s a boy

at the bus stop who dances

in place: knit cap, heavy coat, an extra

chromosome, perhaps. Sometimes he raises

his arms and spins. The world starts with him.

by Jeffry Bahr

from Rattle #16, Winter 2001

My heart. Your soul. A Pandemic Anthology

Philip Graham in Ninth Letter:

When I saw artist Nikki Terry’s painting my heart. your soul., I felt it expressed everything Ninth Letter was attempting to convey in this pandemic anthology. While at first glance its stark red colors could serve as an x-ray of this year’s tormented emotional landscape, a closer look reveals a meeting place between heart and soul, a necessary balance, something even calming and redemptive in the midst of trouble. While its essential tenderness is personal (it was created in 2018), Terry’s painting also points to a larger truth for us all: that our need for connection in the face of tribulation can help us make it through.

The various entries in this anthology (including two additional works of art by Nikki Terry) engage with the multiple calamities of 2020 and live for connection. Tabish Khair’s pandemic sonnets reach across the centuries for inspiration, transforming the iambic pentameter of Shakespeare’s love sonnets into the crushing details of our Covid landscape: endangered healthcare workers, the further enriching of the rich during the pandemic, and the inevitably brief resurgence of the natural world as humans hunker down. The hidden story behind James Lu’s account of China’s cynical betrayal of its citizens living abroad during the pandemic is the Chinese people’s hunger for a government they can trust. Gladys Vercammen-Grandjean’s delicate short essay tells us of a Dutch word that has gained a whole new level of meaning during this year’s extended quarantines: “skin-hunger.”

More here.

Saturday, October 10, 2020

Sympathy for the Devil

Hermione Lee in the New York Review of Books:

John Ames, the old preacher who has lived in the small town of Gilead, Iowa, all his life, where he is the Congregationalist minister, tells the story of Gilead, the first of a series of interconnected novels that Marilynne Robinson has been publishing since 2004. Toward the end of that meditative, troubled, searching book, the dying minister says that other peoples’ souls are, in the end, a mystery to him. Try as we might, “in every important way we are such secrets from each other…there is a separate language in each of us.” Each human being, he thinks, “is a little civilization built on the ruins of any number of preceding civilizations.” We have “resemblances,” which enable us to live together and socialize. “But all that really just allows us to coexist with the inviolable, untraversable, and utterly vast spaces between us.”

The passage is at the heart of these four books, Gilead, Home, Lila, and now Jack. (The much earlier Housekeeping, published in 1980, stands edge-on to the Gilead novels. It is set in a different part of America, with different characters and a different tone, and, unlike the later books, is entirely about women’s lives. But it shares their preoccupation with loneliness, outcasts, poverty, and the possibility of finding again what has been lost.) Ames’s ruminations on the soul are prolix, philosophical, and profoundly sad. And Robinson’s work, which takes its inspiration as much from Virgil and classical tragedy as it does from American Protestant literature, is heavy with lacrimae rerum, the “great sadness that pervades human life.”

More here.

Thirty glorious years

Jonathan Hopkin in Aeon:

Jonathan Hopkin in Aeon:

With the end of the Second World War, the economies of western Europe and North America began a period of spectacular growth. Between 1950 and 1973 GDP doubled or more. This prosperity was broadly shared, with consistent growth in living standards for rich and poor alike and the emergence of a broad middle class. The French call it les trente glorieuses – the 30 glorious years – while the Italians describe it as il miracolo economico. The story of how this golden age of shared economic growth came to be has almost been forgotten, despite it being less than a century ago. There has never been a more urgent time to remind ourselves.

How did western countries, in one quarter of the 20th century, manage to increase both equality and economic efficiency? Why did this virtuous combination ultimately fall apart by the end of the century? The answer lies in the awkward relationship between democracy and capitalism, the former founded on equal political rights, the latter tending to accentuate differences between citizens based on talent, luck or inherited advantage. Democracy has the potential to curb capitalism’s inherent tendency to generate inequality. This very inequality can undermine the ability of democratic institutions to ensure that the economy works for the majority.

The rise and fall of democratic capitalism in the postwar era is one of the most important events in modern history.

More here.

Think Jacques Derrida was a charlatan? Look again

Julian Baggini makes the case in Prospect:

Julian Baggini makes the case in Prospect:

In May 1992, academics at the University of Cambridge reacted with outrage to a proposed honorary degree from their venerable institution to Jacques Derrida. A letter to the Times from 14 international philosophers followed, protesting that “M Derrida’s work does not meet accepted standards of clarity and rigour.”

Depending on your viewpoint, the incident marked the zenith or nadir of Anglo-American analytic philosophy’s resistance to what it saw as the obfuscation and sophistry of its continental European cousin. To them Derrida was a peddler of “tricks and gimmicks,” a cheap entertainer whose stock in trade was “elaborate jokes and puns.”

The irony is that the protests showed a shocking lack of rigour themselves. As Peter Salmon points out in his brilliant biography An Event, Perhaps, Derrida had never used the puerile pun “logical phallusies” that the letter writers attributed to him. This was remarkably sloppy since “it is not as though neologisms ripe for their sort of mockery are hard to find.” Salmon concludes that “none of them had taken the time to read any of Derrida’s work.”

It would have been understandable if some had tried but quickly given up. One of Derrida’s examiners at his prestigious high school, the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, wrote of his work: “The answers are brilliant in the very same way that they are obscure.” His work as an undergraduate was no easier to decipher. Louis Althusser said that he could not grade his dissertation because “it’s too difficult, too obscure.” Michel Foucault could do little better, remarking: “Well, it’s either an F or an A+.”

The Derrida portrayed by Salmon would have shared these doubts. His “nagging fear that those who saw him as a charlatan were right never left him.”

More here.