Samantha Rose Hill in Aeon:

Samantha Rose Hill in Aeon:

What prepares men for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience …

– From The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) by Hannah Arendt

‘Please write regularly, or otherwise I am going to die out here.’ Hannah Arendt didn’t usually begin letters to her husband this way, but in the spring of 1955 she found herself alone in a ‘wilderness’. After the publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism, she was invited to be a visiting lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley. She didn’t like the intellectual atmosphere. Her colleagues lacked a sense of humour, and the cloud of McCarthyism hung over social life. She was told there would be 30 students in her undergraduate classes: there were 120, in each. She hated being on stage lecturing every day: ‘I simply can’t be exposed to the public five times a week – in other words, never get out of the public eye. I feel as if I have to go around looking for myself.’ The one oasis she found was in a dockworker-turned-philosopher from San Francisco, Eric Hoffer – but she wasn’t sure about him either: she told her friend Karl Jaspers that Hoffer was ‘the best thing this country has to offer’; she told her husband Heinrich Blücher that Hoffer was ‘very charming, but not bright’.

Arendt was no stranger to bouts of loneliness. From an early age, she had a keen sense that she was different, an outsider, a pariah, and often preferred to be on her own. Her father died of syphilis when she was seven; she faked all manner of illnesses to avoid going to school as a child so she could stay at home; her first husband left her in Berlin after the burning of the Reichstag; she was stateless for nearly 20 years. But, as Arendt knew, loneliness is a part of the human condition. Everybody feels lonely from time to time.

More here.

F

F DeLillo’s new one is a pristine disaster novel with apocalyptic overtones. It’s a Stephen King novel scored by Philip Glass instead of Chuck Berry. A plane from Paris to Newark crash-lands. Two of the main characters are on this flight, and they survive. Power grids have gone down all over the world. Aliens? The Chinese? The Joker? QAnon?

DeLillo’s new one is a pristine disaster novel with apocalyptic overtones. It’s a Stephen King novel scored by Philip Glass instead of Chuck Berry. A plane from Paris to Newark crash-lands. Two of the main characters are on this flight, and they survive. Power grids have gone down all over the world. Aliens? The Chinese? The Joker? QAnon? Sometime in the coming months, our prayers will have been answered. The researchers will have pulled their all-nighters, mountains will have been moved, glass vials will have been shipped, and a vaccine that protects us from the novel coronavirus will be here. We will all clamber to get it so we can go back to school, work, restaurants, and life. All of us, that is, except for people like Marcus Nel-Jamal Hamm. Hamm, a Black actor and professional wrestler, is what some might call an “anti-vaxxer,” though he finds that term derogatory and reductive. Since about 2013, he’s been running a Facebook page called “Over Vaccination Nation,” which now has more than 3,000 followers. One recent post

Sometime in the coming months, our prayers will have been answered. The researchers will have pulled their all-nighters, mountains will have been moved, glass vials will have been shipped, and a vaccine that protects us from the novel coronavirus will be here. We will all clamber to get it so we can go back to school, work, restaurants, and life. All of us, that is, except for people like Marcus Nel-Jamal Hamm. Hamm, a Black actor and professional wrestler, is what some might call an “anti-vaxxer,” though he finds that term derogatory and reductive. Since about 2013, he’s been running a Facebook page called “Over Vaccination Nation,” which now has more than 3,000 followers. One recent post  David Byrne’s American Utopia begins with the sound of birds for close to a minute before revealing the singer, seated alone at a desk, holding a human brain. Otherwise, the stage is empty, save for a curtain composed of hundreds of thin metal chains that line the walls and shimmer like streaks of rain. As in Stop Making Sense, the 1984 Talking Heads concert film, band members emerge as the show progresses. They, like Byrne, are dressed in gray suits, with no shoes, no socks. It’s a stripped-down look for a show that is as cerebral and subtly political as it is raucous and joyful. Byrne wrote or cowrote almost every song in it—a few are from his 2018 album of the same name, and about half are familiar Talking Heads tunes, including a version of “Once in a Lifetime” that’s somehow even more poignant than the original. But it’s a cover of Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout,” one of American Utopia’s last songs, that becomes its soul. In between, Byrne muses, philosophically and humorously, on whether babies are smarter than grown-ups and why people are more interesting to look at than, say, a bag of potato chips.

David Byrne’s American Utopia begins with the sound of birds for close to a minute before revealing the singer, seated alone at a desk, holding a human brain. Otherwise, the stage is empty, save for a curtain composed of hundreds of thin metal chains that line the walls and shimmer like streaks of rain. As in Stop Making Sense, the 1984 Talking Heads concert film, band members emerge as the show progresses. They, like Byrne, are dressed in gray suits, with no shoes, no socks. It’s a stripped-down look for a show that is as cerebral and subtly political as it is raucous and joyful. Byrne wrote or cowrote almost every song in it—a few are from his 2018 album of the same name, and about half are familiar Talking Heads tunes, including a version of “Once in a Lifetime” that’s somehow even more poignant than the original. But it’s a cover of Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout,” one of American Utopia’s last songs, that becomes its soul. In between, Byrne muses, philosophically and humorously, on whether babies are smarter than grown-ups and why people are more interesting to look at than, say, a bag of potato chips. In just a few years, scientists at Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will launch the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), using the world’s biggest digital camera for ground-based astronomy to take the most detailed pictures of the night sky ever made. When they do, two of the most important things they’ll look for are dark matter and dark energy, the mysterious, invisible substances that make up about 95% of our universe.

In just a few years, scientists at Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will launch the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), using the world’s biggest digital camera for ground-based astronomy to take the most detailed pictures of the night sky ever made. When they do, two of the most important things they’ll look for are dark matter and dark energy, the mysterious, invisible substances that make up about 95% of our universe. Even

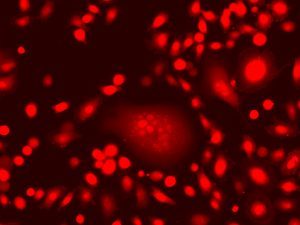

Even  Species adapt to survive in a changing environment through the process of evolution. Evolutionary processes can also take place at the cellular level. Dr Sarah Amend of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA, is investigating poly-aneuploid cancer cells (PACCs). These large, DNA-laden cells, which are more common in metastatic cancer, develop evolvability: the capacity to evolve. Dr Amend believes that targeting the evolvability of PACCs and exploiting cancer ecology could offer new potential treatment routes for patients with metastatic cancer. When a person dies from cancer, the cause is usually not the primary tumour, but the metastases. Metastases are secondary tumours that develop when cancerous cells leave the original tumour and travel to other parts of the body. Despite many recent advances in medical science, metastases are extremely difficult to treat. While people with metastatic cancer can sometimes survive for many months or years, the disease is almost always fatal, leading to the deaths of 10 million cancer patients globally every year.

Species adapt to survive in a changing environment through the process of evolution. Evolutionary processes can also take place at the cellular level. Dr Sarah Amend of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA, is investigating poly-aneuploid cancer cells (PACCs). These large, DNA-laden cells, which are more common in metastatic cancer, develop evolvability: the capacity to evolve. Dr Amend believes that targeting the evolvability of PACCs and exploiting cancer ecology could offer new potential treatment routes for patients with metastatic cancer. When a person dies from cancer, the cause is usually not the primary tumour, but the metastases. Metastases are secondary tumours that develop when cancerous cells leave the original tumour and travel to other parts of the body. Despite many recent advances in medical science, metastases are extremely difficult to treat. While people with metastatic cancer can sometimes survive for many months or years, the disease is almost always fatal, leading to the deaths of 10 million cancer patients globally every year. In fact, not only will a focus on the effort to eliminate racial disparities not take us in the direction of a more equal society, it isn’t even the best way of eliminating racial disparities themselves. If the objective is to eliminate black poverty rather than simply to benefit the upper classes, we believe the diagnosis of racism is wrong, and the cure of antiracism won’t work. Racism is real and antiracism is both admirable and necessary, but extant racism isn’t what principally produces our inequality and antiracism won’t eliminate it. And because racism is not the principal source of inequality today, antiracism functions more as a misdirection that justifies inequality than a strategy for eliminating it.

In fact, not only will a focus on the effort to eliminate racial disparities not take us in the direction of a more equal society, it isn’t even the best way of eliminating racial disparities themselves. If the objective is to eliminate black poverty rather than simply to benefit the upper classes, we believe the diagnosis of racism is wrong, and the cure of antiracism won’t work. Racism is real and antiracism is both admirable and necessary, but extant racism isn’t what principally produces our inequality and antiracism won’t eliminate it. And because racism is not the principal source of inequality today, antiracism functions more as a misdirection that justifies inequality than a strategy for eliminating it. Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months – in Brussels and in Berlin too.

Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months – in Brussels and in Berlin too. The utopian ideal of globalization has imploded over the past decade. Rising demand in Western countries for greater state control over the economy reflects a range of grievances, from a chronic shortage of well-compensated work to a sense of national decline. In the United States, the dearth of domestic supply chains exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has only heightened alarm over the acute infrastructural weaknesses decades of outsourced production have created. Post-industrial society, rather than an advanced stage of shared affluence, is not only more unequal but fundamentally insecure. Rich but increasingly oligarchic countries are experiencing what we might call, following scholars of democratization, a dramatic “de-consolidation” of development.

The utopian ideal of globalization has imploded over the past decade. Rising demand in Western countries for greater state control over the economy reflects a range of grievances, from a chronic shortage of well-compensated work to a sense of national decline. In the United States, the dearth of domestic supply chains exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has only heightened alarm over the acute infrastructural weaknesses decades of outsourced production have created. Post-industrial society, rather than an advanced stage of shared affluence, is not only more unequal but fundamentally insecure. Rich but increasingly oligarchic countries are experiencing what we might call, following scholars of democratization, a dramatic “de-consolidation” of development. In 1879 Josiah Royce wrote a letter from Berkeley, to William James at Harvard, describing the intellectual condition of his home state: “There is no philosophy in California. From Siskiyou to Ft. Yuma, and from the Golden Gate to the summit of the Sierras there could not be found brains enough to accomplish the formation of a single respectable idea that was not manifest plagiarism.” From any other author, these words could only be received as complaint, but Royce himself understands them as a neutral description of fact, perhaps even as subtle praise for a land he deems ill-disposed to the convection of metaphysical hot air.

In 1879 Josiah Royce wrote a letter from Berkeley, to William James at Harvard, describing the intellectual condition of his home state: “There is no philosophy in California. From Siskiyou to Ft. Yuma, and from the Golden Gate to the summit of the Sierras there could not be found brains enough to accomplish the formation of a single respectable idea that was not manifest plagiarism.” From any other author, these words could only be received as complaint, but Royce himself understands them as a neutral description of fact, perhaps even as subtle praise for a land he deems ill-disposed to the convection of metaphysical hot air. Yet while researchers celebrate the achievement, they stress that the newfound compound — created by a team led by

Yet while researchers celebrate the achievement, they stress that the newfound compound — created by a team led by