Category: Recommended Reading

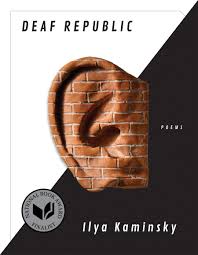

Interview With Ilya Kaminsky

Joe Dunthorne and Ilya Kaminsky at The White Review (via The Book Haven):

Twenty-five years after he and his parents fled Ukraine, Ilya Kaminsky went back to Odessa, the city of his childhood. As he explored the city, he did not feel that he had truly returned until he removed his hearing aids. He has written that, for him, Odessa is ‘a silent city, where the language is invisibly linked to my father’s lips moving as I watch his mouth repeat stories again and again. He turns away. The story stops.’

Twenty-five years after he and his parents fled Ukraine, Ilya Kaminsky went back to Odessa, the city of his childhood. As he explored the city, he did not feel that he had truly returned until he removed his hearing aids. He has written that, for him, Odessa is ‘a silent city, where the language is invisibly linked to my father’s lips moving as I watch his mouth repeat stories again and again. He turns away. The story stops.’

In DEAF REPUBLIC, Kaminsky tells the story of a town, Vasenka, during a time of unrest when public gatherings are prohibited. Soldiers come to break up a crowd watching a puppet show in the central square. Petya, a deaf boy, is the only one who does not hear the army sergeant yelling ‘disperse immediately’ and he carries on laughing at the puppets. Moments later, he is killed. The gunshot becomes the last thing that the people of the town hear. From then on, the citizens refuse to acknowledge the sound of the occupying forces. ‘At six a.m., when soldiers compliment girls in the alleyway, the girls slide by, pointing to their ears.’

more here.

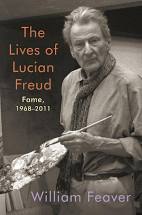

The Brilliance and Brutality of Lucian Freud

Andrew Marr at the New Statesman:

There is a much darker side to his life, too. The relentless womanising, including with vulnerable people far, far younger than him; the children so numerous they were hard to keep track of; the brutal break-ups, vicious feuds and spasms of verbal cruelty that made Freud, for many people, an impossibly sulphurous figure, a coldly brilliant predator smoking with menace. Observing him at the Jewish wedding in London of the painter RB Kitaj, the poet Stephen Spender whispered to Feaver: “I can’t stand being in the same place with Lucian. He is an evil man.”

There is a much darker side to his life, too. The relentless womanising, including with vulnerable people far, far younger than him; the children so numerous they were hard to keep track of; the brutal break-ups, vicious feuds and spasms of verbal cruelty that made Freud, for many people, an impossibly sulphurous figure, a coldly brilliant predator smoking with menace. Observing him at the Jewish wedding in London of the painter RB Kitaj, the poet Stephen Spender whispered to Feaver: “I can’t stand being in the same place with Lucian. He is an evil man.”

How is a biographer and a friend supposed to bridge this impossible gap of perception? Freud’s doctor, Michael Gormley, perhaps comes nearest to a balanced picture when he described him as “one of those wonderful people who owned his self. His selfishness. He had an addictive personality. Addictive people love intensity; it’s the nature of the personality, ruling everything…”

more here.

Dying in a Leadership Vacuum

The Editors of The New England Journal of Medicine:

Covid-19 has created a crisis throughout the world. This crisis has produced a test of leadership. With no good options to combat a novel pathogen, countries were forced to make hard choices about how to respond. Here in the United States, our leaders have failed that test. They have taken a crisis and turned it into a tragedy. The magnitude of this failure is astonishing.

Covid-19 has created a crisis throughout the world. This crisis has produced a test of leadership. With no good options to combat a novel pathogen, countries were forced to make hard choices about how to respond. Here in the United States, our leaders have failed that test. They have taken a crisis and turned it into a tragedy. The magnitude of this failure is astonishing.

…The response of our nation’s leaders has been consistently inadequate. The federal government has largely abandoned disease control to the states. Governors have varied in their responses, not so much by party as by competence. But whatever their competence, governors do not have the tools that Washington controls. Instead of using those tools, the federal government has undermined them. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which was the world’s leading disease response organization, has been eviscerated and has suffered dramatic testing and policy failures. The National Institutes of Health have played a key role in vaccine development but have been excluded from much crucial government decision making. And the Food and Drug Administration has been shamefully politicized,3 appearing to respond to pressure from the administration rather than scientific evidence. Our current leaders have undercut trust in science and in government,4 causing damage that will certainly outlast them. Instead of relying on expertise, the administration has turned to uninformed “opinion leaders” and charlatans who obscure the truth and facilitate the promulgation of outright lies.

More here.

Without Trump Onstage, There Is No Chaos

Russell Berman in The Atlantic:

In perhaps the most chaotic week of a chaotic presidency, what was most surprising about tonight’s vice-presidential debate was how oddly normal it felt.

In perhaps the most chaotic week of a chaotic presidency, what was most surprising about tonight’s vice-presidential debate was how oddly normal it felt.

Five days ago, the president of the United States was hospitalized after contracting a virus that has killed more than 200,000 Americans. There were legitimate questions about whether Donald Trump could execute the powers of his office. In the days since, dozens of people who work in or closely with the White House and the president’s reelection campaign have become infected, including senior officials in the government, the Republican Party, and the U.S. military. The president has proclaimed himself to be “cured” of the virus, but the extent of his illness remains unknown to the public. Meanwhile, Trump has continued to undermine the integrity of the election, refused to commit to relinquishing power if he loses, and, as recently as this afternoon, suggested that his opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden, “shouldn’t be allowed” to even run.

…Trump was, of course, an invisible star of the night. It was his record up for debate, and his name was mentioned, on average, once a minute. But his mere absence transformed the forum into something quieter, more approachable. It served as a reminder that although the fissures in American society that he has exploited predate his arrival as a politician, the chaos of the past four years belongs to him. Trump is the chaos, and without him, there is no chaos. At least that’s the easy answer. When Pence was given a chance to guarantee a peaceful transfer of power if Biden wins, he, too, refused to do so—though in his typical fashion, the answer was a simple deflection, not a veiled threat laden with the suggestion of violence. Trump’s exit won’t erase the deep political disagreements Americans have, nor will it automatically restore the norms he has weakened. But tonight’s debate hinted that, at a minimum, those battles will proceed more civilly.

If that is the main takeaway that viewers have, perhaps the advantage goes to Biden, no matter how effectively Pence made the president’s case tonight. After all, it is Biden who is offering America a return to normalcy—a calmer, yes, even a more boring presidency. Tonight the country saw what that might look like. It watched, in Pence and Harris, a pair of career politicians take the stage once again, offering a window into a world without Donald Trump at its center.

More here.

Louise Glück wins Nobel prize in literature

Alison Flood in The Guardian:

The poet Louise Glück has become the first American woman to win the Nobel prize for literature in 27 years, cited for “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”.

The poet Louise Glück has become the first American woman to win the Nobel prize for literature in 27 years, cited for “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”.

Glück is the 16th woman to win the Nobel, and the first American woman since Toni Morrison took the prize in 1993. The American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan was a surprise winner in 2016.

One of America’s leading poets, the 77-year-old writer has won the Pulitzer prize and the National Book Award, tackling themes including childhood and family life, often reworking Greek and Roman myths.

The chair of the Nobel prize committee, Anders Olsson, hailed Glück’s “candid and uncompromising” voice, which is “full of humour and biting wit”. Her 12 collections of poetry, from Faithful and Virtuous Night to The Wild Iris are “characterised by a striving for clarity”, he added, comparing her to Emily Dickinson with her “severity and unwillingness to accept simple tenets of faith”.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Atlantis—A Lost Sonnet

How on earth did it happen, I used to wonder

that a whole city—arches, pillars, colonnades,

not to mention vehicles and animals—had all

one fine day gone under?

I mean, I said to myself, the world was small then.

Surely a great city must have been missed?

I miss our old city —

white pepper, white pudding, you and I meeting

under fanlights and low skies to go home in it. Maybe

what really happened is

this: the old fable-makers searched hard for a word

to convey that what is gone is gone forever and

never found it. And so, in the best traditions of

where we come from, they gave their sorrow a name

and drowned it.

by Eavan Boland

from Domestic Violence

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2007

Wednesday, October 7, 2020

The Dark Matter Enigma

Jean-Pierre Luminet in Inference Review:

Recent surveys make possible a precise estimation of the composition of the observable universe.7 Luminous matter represents only 0.5% of the total; dark energy, a form of non-material and antigravitational energy, 68%. The remaining 32% is attributed to dark matter—a contribution that is almost entirely invisible to telescopes.

The true nature of dark matter is one of the most significant challenges in modern astrophysics, especially since its distribution is far from uniform. Consider the galaxies Dragonfly 44 and NGC1052-DF2. Discovered in 2015, Dragonfly 44 has a mass comparable to the Milky Way, but appears to be almost exclusively dark matter (99.99%).8 By contrast, NGC1052-DF2, which was discovered in 2018, appears to be devoid of dark matter.9

More here.

This Supreme Court Term Will End With Either Catastrophe or 13 Justices

Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern in Slate:

At the first debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, Biden refused to say whether he’d expand the Supreme Court if Republicans confirm Barrett, insisting that the issue is a “distraction.” He’s wrong. Broaching the conversation about systemic reform after the election will be too late. And the coming Supreme Court term, which begins Monday, reflects just some of what’s at stake, this week, this month, and in the months ahead. The debate about structural changes to the court can’t wait until a hypothetical future in which everything has settled down. That future has already vanished.

At the first debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, Biden refused to say whether he’d expand the Supreme Court if Republicans confirm Barrett, insisting that the issue is a “distraction.” He’s wrong. Broaching the conversation about systemic reform after the election will be too late. And the coming Supreme Court term, which begins Monday, reflects just some of what’s at stake, this week, this month, and in the months ahead. The debate about structural changes to the court can’t wait until a hypothetical future in which everything has settled down. That future has already vanished.

On the docket just in the weeks to come, there is a blockbuster case that seeks to put a stake through the heart of the Affordable Care Act, in the midst of a pandemic—a challenge Barrett would seem to favor. Also on the docket is a case about a Philadelphia foster care agency that refuses to work with same-sex couples and claims that it constitutes religious discrimination if the city refuses to subsidize it with taxpayer dollars. In case that weren’t enough, the court may also hear a case that could strip same-sex couples of equal parenting rights. Moving from religion to guns, the court has been itching to expand the Second Amendment, and Barrett has made plain that she would go further than even most conservative judges to permit guns.

More here.

Richard Feynman’s Computer Heuristics Lecture in 1985

On ‘My Morningless Mornings’

Pete Tosiello at Full Stop:

Even when ruminating upon dream diaries, werewolves, and vampires, Golberg’s erudition imbues her childlike wonder with a preacher’s certitude. She finds analogies across cultures and languages, weaving centuries-old philosophies into her personal examination of late-night gloom and early-morning revelation. There’s a selective nature to her surveys, some of which take the form of art and literary criticism. But the essays build upon successive themes, Golberg’s metaphors compounding and accreting into a more solid, ambitious exploration of identity. Who are we, these essays ask, and when are we most ourselves? “I suppose this was Jung’s point all along, that the dreamworld is not separate from the everyday world,” she considers, “that we enact our dreams in daily life as we enact our daily life in dreams, and that to divide these parts of ourselves — the sleeping self and the wide-awake self — makes us incomplete.” These analyses make approachable essays even for readers not steeped in the work of Japanese novelists and nineteenth-century painters.

Even when ruminating upon dream diaries, werewolves, and vampires, Golberg’s erudition imbues her childlike wonder with a preacher’s certitude. She finds analogies across cultures and languages, weaving centuries-old philosophies into her personal examination of late-night gloom and early-morning revelation. There’s a selective nature to her surveys, some of which take the form of art and literary criticism. But the essays build upon successive themes, Golberg’s metaphors compounding and accreting into a more solid, ambitious exploration of identity. Who are we, these essays ask, and when are we most ourselves? “I suppose this was Jung’s point all along, that the dreamworld is not separate from the everyday world,” she considers, “that we enact our dreams in daily life as we enact our daily life in dreams, and that to divide these parts of ourselves — the sleeping self and the wide-awake self — makes us incomplete.” These analyses make approachable essays even for readers not steeped in the work of Japanese novelists and nineteenth-century painters.

more here.

The Poetry of Eavan Boland

Theo Dorgan at the Dublin Review of Books:

Steadily, poem by poem and book by book, Eavan worked her way into the heart of darkness, not in the Conradian sense of course, but into the centre of those marginal, penumbral zones outside the spotlight of what was “officially” deemed worthy of being remembered. Hers was a double journey ‑ the poet finding her way into the self-granted warrant of her craft, the citizen struggling for the vindication of women, for a more amplified and more truthful narrative of Ireland. Her method was her purpose: in confronting exclusion, in the historical sense, she simultaneously chose to examine her own path into permission, into the poem, ever-present to herself, always questioning her step-by-step progress into her own gathering experience of making. And at the same time, not as a polemicist but as a citizen, she was attempting to formulate, or reformulate, a more ample and truthful vision of Ireland. By the time she had arrived at the pared back landscapes and poemscapes of Outside History and Against Love Poetry, it seems to me that she had succeeded in fusing her double quest: she had found a way to speak plainly of and for all those whom history had cast aside, a neglect, often deliberate, that was both political and moral; and at the same time she had found in herself a voice she could finally consider adequate to her subject and to the unforgiving demands of her craft.

Steadily, poem by poem and book by book, Eavan worked her way into the heart of darkness, not in the Conradian sense of course, but into the centre of those marginal, penumbral zones outside the spotlight of what was “officially” deemed worthy of being remembered. Hers was a double journey ‑ the poet finding her way into the self-granted warrant of her craft, the citizen struggling for the vindication of women, for a more amplified and more truthful narrative of Ireland. Her method was her purpose: in confronting exclusion, in the historical sense, she simultaneously chose to examine her own path into permission, into the poem, ever-present to herself, always questioning her step-by-step progress into her own gathering experience of making. And at the same time, not as a polemicist but as a citizen, she was attempting to formulate, or reformulate, a more ample and truthful vision of Ireland. By the time she had arrived at the pared back landscapes and poemscapes of Outside History and Against Love Poetry, it seems to me that she had succeeded in fusing her double quest: she had found a way to speak plainly of and for all those whom history had cast aside, a neglect, often deliberate, that was both political and moral; and at the same time she had found in herself a voice she could finally consider adequate to her subject and to the unforgiving demands of her craft.

more here.

Eavan Boland at Cornell

When Evolution Is Infectious: How “probiotic epidemics” help wildlife—and us—survive

Moises Velasquez-Manoff in Nautilus:

Ever since Charles Darwin taught us that life is constantly driven to change by myriad pressures—that species are not static, but are constantly morphing—biologists have debated how fast those changes can occur. The discovery of the genome a century after Darwin published On the Origin of Species seemed to demarcate an upper limit. Animals could evolve only as fast as advantageous genes could arise and spread, and as existing genomes could be reshuffled through sexual reproduction. But then came “epigenetics”: Some adaptation could occur more quickly, without changing genes themselves, but by altering how existing genes translated into living flesh. Rosenberg and others are proposing an even quicker process—organisms can adapt rapidly by switching their symbiotic microbes. The very quality that makes pandemics so terrifying—rapid contagion—may also drive mass adaptation.

Ever since Charles Darwin taught us that life is constantly driven to change by myriad pressures—that species are not static, but are constantly morphing—biologists have debated how fast those changes can occur. The discovery of the genome a century after Darwin published On the Origin of Species seemed to demarcate an upper limit. Animals could evolve only as fast as advantageous genes could arise and spread, and as existing genomes could be reshuffled through sexual reproduction. But then came “epigenetics”: Some adaptation could occur more quickly, without changing genes themselves, but by altering how existing genes translated into living flesh. Rosenberg and others are proposing an even quicker process—organisms can adapt rapidly by switching their symbiotic microbes. The very quality that makes pandemics so terrifying—rapid contagion—may also drive mass adaptation.

To support the hologenome theory, Rosenberg and others look to the study of the human microbiome, particularly the example of Clostridium difficile. People tend to acquire the bacterium during hospital stays and after they’ve “clearcut” their native microbes with antibiotics directed at another infection. C. difficile then blooms. Patients can end up delirious and in pain, weakened by an unremitting torrent of bloody diarrhea. The microbe infects an estimated 500,000 Americans yearly, killing some 29,000 of them within a month.

C. difficile is increasingly resistant to antibiotics, so further treatment fails in about 1 in 5 cases. For this subset, the “fecal transplant” is nearly miraculous. The procedure involves “implanting” stool from a healthy person, via enema, or in pills, into the intestines of one stricken with C. difficile. And it’s 94 percent effective at curing C. difficile. It works, scientists think, by restoring a fully functioning microbial ecosystem in one fell swoop. The donor’s tight-knit community deprives the pathogen C. difficile of an ecological niche, squeezing it from the gut. Technically, stool transplants are not “probiotic epidemics.” But the principle the transplant illustrates—that native microbes prevent disease, and that tweaking those microbes can fend off a deadly infection—is precisely what scientists think could drive a probiotic epidemic.

More here.

Pioneers of revolutionary CRISPR gene editing win chemistry Nobel

Callaway and Ledford in Nature:

It’s CRISPR. Two scientists who pioneered the revolutionary gene-editing technology are the winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The Nobel Committee’s selection of Emmanuelle Charpentier, now at the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, and Jennifer Doudna, at the University of California, Berkeley, puts to rest years of speculation as to who would be recognized for their work developing the CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing tools. The technology has swept through labs worldwide and has countless applications: researchers hope to use it to alter human genes to eliminate diseases, create hardier plants, wipe out pathogens and more.

It’s CRISPR. Two scientists who pioneered the revolutionary gene-editing technology are the winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The Nobel Committee’s selection of Emmanuelle Charpentier, now at the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, and Jennifer Doudna, at the University of California, Berkeley, puts to rest years of speculation as to who would be recognized for their work developing the CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing tools. The technology has swept through labs worldwide and has countless applications: researchers hope to use it to alter human genes to eliminate diseases, create hardier plants, wipe out pathogens and more.

Several other scientists, in addition to Charpentier and Doudna, have been cited — and recognized in other high-profile awards — as key contributors in the development of CRISPR. They include Feng Zhang at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, George Church at MIT and biochemist Virginijus Siksnys at Vilnius University in Lithuania. Doudna was “really sound asleep” when her buzzing phone woke her and she took a call from a Nature reporter, who broke the news. “I grew up in a small town in Hawaii and I never in a hundred million years would have imagined this happening,” says Doudna. “I’m really stunned, I’m just completely in shock.” “I know so many wonderful scientists who will never receive this, for reasons that have nothing to do with the fact that they are wonderful scientists,” Doudna says. “I am really kind of humbled.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

The Precision

There is a modesty in nature. In the small

of it and in the strongest. The leaf moves

just the amount the breeze indicates

and nothing more. In the power of lust, too,

there can be a quiet and clarity, a fusion

of exact moments. There is a silence of it

inside the thundering. And when the body swoons,

it is because the heart knows its truth.

There is directness and equipoise in the fervor,

just as the greatest turmoil has precision.

Like the discretion a tornado has when it tears

down building after building, house by house.

It is enough, Kafka said, that the arrow fit

exactly into the wound that it makes. I think

about my body in love as I look down on these

lavish apple trees and the workers moving

with skill from one to the next, singing.

by Linda Gregg

from Things and Flesh

Graywolf Press, 1999

Tuesday, October 6, 2020

Jürgen Habermas: Germany’s second chance

Jürgen Habermas in Blätter:

Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months—in Brussels and in Berlin too.

Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months—in Brussels and in Berlin too.

At first glance it might seem a bit far-fetched to compare the overcoming of a world order divided into two opposing camps and the global spread of victorious capitalism with the elemental nature of a pandemic that caught us off-guard and the related global economic crisis happening on an unprecedented scale. Yet if we Europeans can find a constructive response to the shock, this might provide a parallel between the two world-shattering events.

In those days, German and European unification were linked as if joined at the hip. Today, any connection between these two processes, self-evident then, is not so obvious. Yet, while Germany’s national-day celebration (October 3rd) has remained curiously pallid during the last three decades, one might speculate along the following lines: imbalances within the German unification process are not the reason for the surprising revival of its European counterpart but the historical distance which we have now gained from those domestic problems has helped to make the federal government finally revert to the historic task it had put to one side—giving political shape and definition to Europe’s future.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Sean B. Carroll on Randomness and the Course of Evolution

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Evolution is a messy business, involving as it does selection pressures, mutations, genetic drift, and the effects of random external interventions. So in the end, how much of it is predictable, and how much is in the hands of chance? Today we’re thrilled to have as a guest my evil (but more respectable, by most measures) twin, the biologist Sean B. Carroll. Sean is both a leader of the modern evo-devo revolution, and a wonderful and diverse writer. We talk about the importance of randomness and unpredictability in life, from the evolution of species to the daily routine of every individual.

Evolution is a messy business, involving as it does selection pressures, mutations, genetic drift, and the effects of random external interventions. So in the end, how much of it is predictable, and how much is in the hands of chance? Today we’re thrilled to have as a guest my evil (but more respectable, by most measures) twin, the biologist Sean B. Carroll. Sean is both a leader of the modern evo-devo revolution, and a wonderful and diverse writer. We talk about the importance of randomness and unpredictability in life, from the evolution of species to the daily routine of every individual.

More here.

A Famous Misanthrope Shows His Heartwarming Side

Daphne Merkin at Bookforum:

Did Larkin’s parents fuck him up? According to his sister Catherine (“Kitty”), ten years his senior, both parents “worshipped” Philip. All the same, they have undoubtedly been demonized—sometimes by the poet himself. There were the sour references he made to his childhood in his poetry (“a forgotten boredom”), and then there was his adamantine bachelor’s decision not to marry, seemingly because he did not want to replicate what appears to have been an unhappy parental union. More damning facts have emerged since Larkin died in 1985 at the age of sixty-three, a much-admired and influential figure who had turned down the position of poet laureate a year earlier. These include his father Sydney’s blithe admiration for Nazi Germany, as evidenced by his observing on the first page of his twenty-volume diary (!!) that “those who had visited Germany were much impressed by the good government and order of the country as by the cleanliness and good behavior of the people,” as well as his unrepentant anti-Semitism. As for his mother Eva, Andrew Motion’s 1993 biography of Larkin describes her as “indispensable but infuriating,” like some grating housemaid. Larkin himself characterizes her in a letter to Monica Jones, the longest-running of his several lovers, as “nervy, cowardly, obsessional, boring, grumbling, irritating, self pitying” before going on to amend his portrait: “on the other hand, she’s kind, timid, unselfish, loving.”

Did Larkin’s parents fuck him up? According to his sister Catherine (“Kitty”), ten years his senior, both parents “worshipped” Philip. All the same, they have undoubtedly been demonized—sometimes by the poet himself. There were the sour references he made to his childhood in his poetry (“a forgotten boredom”), and then there was his adamantine bachelor’s decision not to marry, seemingly because he did not want to replicate what appears to have been an unhappy parental union. More damning facts have emerged since Larkin died in 1985 at the age of sixty-three, a much-admired and influential figure who had turned down the position of poet laureate a year earlier. These include his father Sydney’s blithe admiration for Nazi Germany, as evidenced by his observing on the first page of his twenty-volume diary (!!) that “those who had visited Germany were much impressed by the good government and order of the country as by the cleanliness and good behavior of the people,” as well as his unrepentant anti-Semitism. As for his mother Eva, Andrew Motion’s 1993 biography of Larkin describes her as “indispensable but infuriating,” like some grating housemaid. Larkin himself characterizes her in a letter to Monica Jones, the longest-running of his several lovers, as “nervy, cowardly, obsessional, boring, grumbling, irritating, self pitying” before going on to amend his portrait: “on the other hand, she’s kind, timid, unselfish, loving.”

more here.

Daphne Merkin In Conversation With Deborah Solomon