Anandi Mishra in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

As the pandemic raged in 2020, my boyfriend and I were confined within the closed quarters of my two-bedroom flat in Delhi. When the claustrophobia got too heavy, I would step out to rediscover the pleasure of walking with a sense of calm. I would try — and regularly fail — to meet my pre-pandemic mark of eight kilometers every day. It was not a means to an end. I did not have a grand plan. It was just a way to be a part of the city.

As the pandemic raged in 2020, my boyfriend and I were confined within the closed quarters of my two-bedroom flat in Delhi. When the claustrophobia got too heavy, I would step out to rediscover the pleasure of walking with a sense of calm. I would try — and regularly fail — to meet my pre-pandemic mark of eight kilometers every day. It was not a means to an end. I did not have a grand plan. It was just a way to be a part of the city.

“Aimlessness — in art, in life, in writing, in thought, in being — is always more than the lack it names.” So begins Tom Lutz’s most recent collection of essays, Aimlessness. He takes the reader on a journey, knocking on several doors and discovering that all are answered by the same protagonist: the aimless way of life. Stops on the journey include his travels in Mongolia, the Polish author Olga Tokarczuk, the Los Angeles émigré Theodor Adorno, and Friedrich Nietzsche. But his real subject is the unspooling of discursive thought, particularly that seen in writing.

Wandering through the streetscapes of the three most prominent forms of literature — the essay, the poem, and the novel — Lutz finds they all follow a sly, if not obvious, routine of aimlessness.

More here.

A novel computer algorithm, or set of rules, that accurately predicts the orbits of planets in the solar system could be adapted to better predict and control the behavior of the

A novel computer algorithm, or set of rules, that accurately predicts the orbits of planets in the solar system could be adapted to better predict and control the behavior of the  With deft and bold action, Mario Draghi’s unity government in Italy can go some way toward addressing the COVID-19 emergency, laying the groundwork for long-term economic recovery, and restoring Italians’ confidence in their political leaders. But he cannot do it alone.

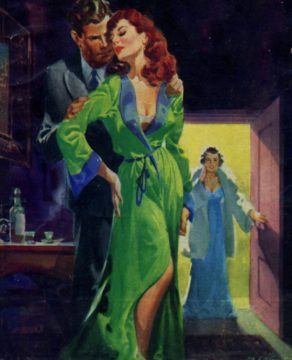

With deft and bold action, Mario Draghi’s unity government in Italy can go some way toward addressing the COVID-19 emergency, laying the groundwork for long-term economic recovery, and restoring Italians’ confidence in their political leaders. But he cannot do it alone. Tolstoy was a moralist. He wrote one novel—Anna Karenina—in which infidelity ends in death, and another—War and Peace—in which his characters endure a thousand pages of political, military and romantic turmoil so as to eventually earn the reward of domestic marital bliss. In the epilogue to War and Peace we encounter his protagonist Natasha, unrecognizably transformed. Throughout the main novel, we had known her as temperamental, beautiful and reflective; as independent, occasionally to the point of selfishness; as readily overwhelmed by ill-fated romantic passions.

Tolstoy was a moralist. He wrote one novel—Anna Karenina—in which infidelity ends in death, and another—War and Peace—in which his characters endure a thousand pages of political, military and romantic turmoil so as to eventually earn the reward of domestic marital bliss. In the epilogue to War and Peace we encounter his protagonist Natasha, unrecognizably transformed. Throughout the main novel, we had known her as temperamental, beautiful and reflective; as independent, occasionally to the point of selfishness; as readily overwhelmed by ill-fated romantic passions. In 2008, months before his election as president, Barack Obama assailed feckless black fathers who had reneged on responsibilities that ought not “to end at conception”. Where had all the black fathers gone, Obama wondered. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander has a simple answer to their whereabouts: they’ve gone to jail.

In 2008, months before his election as president, Barack Obama assailed feckless black fathers who had reneged on responsibilities that ought not “to end at conception”. Where had all the black fathers gone, Obama wondered. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander has a simple answer to their whereabouts: they’ve gone to jail.  On a trip to Warsaw, Poland, in 2019, Richard Freund confronted the history of resistance against the Nazis at a Holiday Inn. Freund, an archaeologist, and professor of Jewish Studies at Christopher Newport University in Virginia, was led by the hotel manager into the basement. “Lo and behold,” Freund says, a section of the Warsaw Ghetto wall was visible. Freund was in Warsaw accompanied by scientists from

On a trip to Warsaw, Poland, in 2019, Richard Freund confronted the history of resistance against the Nazis at a Holiday Inn. Freund, an archaeologist, and professor of Jewish Studies at Christopher Newport University in Virginia, was led by the hotel manager into the basement. “Lo and behold,” Freund says, a section of the Warsaw Ghetto wall was visible. Freund was in Warsaw accompanied by scientists from  Ross Andersen in The Atlantic:

Ross Andersen in The Atlantic: Judith Levine in Boston Review:

Judith Levine in Boston Review: Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB: O

O Lee, or to be formal, Dame Hermione (she was awarded the title in 2013 for “services to literary scholarship”) is a leading member of that generation of British writers — it also includes Richard Holmes, Michael Holroyd, Jenny Uglow and Claire Tomalin — who have brought an infusion of style and imagination to the art of literary biography. She is probably most famous for her

Lee, or to be formal, Dame Hermione (she was awarded the title in 2013 for “services to literary scholarship”) is a leading member of that generation of British writers — it also includes Richard Holmes, Michael Holroyd, Jenny Uglow and Claire Tomalin — who have brought an infusion of style and imagination to the art of literary biography. She is probably most famous for her  Some people think libertarians only care about taxes and regulations. But I was asked not long ago, what’s the most important libertarian accomplishment in history? I said, “the abolition of slavery.”

Some people think libertarians only care about taxes and regulations. But I was asked not long ago, what’s the most important libertarian accomplishment in history? I said, “the abolition of slavery.” Released in the two-hundredth-anniversary year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence,

Released in the two-hundredth-anniversary year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence,