The Dance of the Solids— excerpts

All things are Atoms: Earth and Water, Air

.. And Fire, all, Democritus foretold.

.. Swiss Paracelsus, in his alchemic lair,

.. Saw Sulfur, Salt, and Mercury unfold

.. Amid Millennial hopes of faking Gold.

.. Lavoisier dethroned Phlogiston; then

.. Molecular Analysis made bold

.. Forays into the gases: Hydrogen

Stood naked in the dazzled sight of Learned Men.

The Solid State, however, kept its grains

.. Of Microstructure coarsely veiled until

.. X-ray diffraction pierced the Crystal Planes

.. That roofed the giddy Dance, the taut Quadrille

.. Where Silicon and Carbon Atoms will

.. Link Valencies, four-figured, hand in hand

.. With common Ions and Rare Earths to fill

.. The lattices of Matter, Glass or Sand,

With tiny Excitations, quantitively grand.

The Metals, lustrous Monarchs of the Cave,

.. Are ductile and conductive and opaque

.. Because each Atom generously gave

.. Its own Electrons to a mutual Stake,

.. A Pool that acts as Bond. The Ions take

.. The stacking shape of Spheres, and slip and flow

.. When pressed or dented; thusly Metals make

.. A better Paper Clip than Window,

Are vulnerable to Shear, and, heated, brightly glow.

Ceramic, muddy Queen of human Arts,

.. First served as simple Stone. Feldspar supplied

.. Crude Clay; and Rubies, Porcelain, and Quartz

.. Came each to light. Aluminum Oxide

.. Is typical—a Metal is allied

.. With Oxygen ionically; no free

.. Electrons form a lubricating tide,

.. Hence, Empresslike, Ceramics tend to be

Resistant, porous, brittle, and refractory.

Continue poem here

by John Updike

from Scientific American, 2020

1. Always refer to Iran as the “Islamic Republic” and its government as “the regime” or, better yet, “the Mullahs.”

1. Always refer to Iran as the “Islamic Republic” and its government as “the regime” or, better yet, “the Mullahs.”

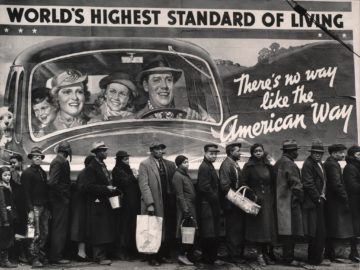

The anti-government stinginess of traditional conservatism, along with the fear of losing social status held by many white people, now broadly associated with Trumpism, have long been connected. Both have sapped American society’s strength for generations, causing a majority of white Americans to rally behind the draining of public resources and investments. Those very investments would provide white Americans — the largest group of the impoverished and uninsured — greater security, too: A new Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study

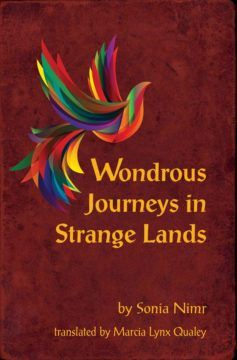

The anti-government stinginess of traditional conservatism, along with the fear of losing social status held by many white people, now broadly associated with Trumpism, have long been connected. Both have sapped American society’s strength for generations, causing a majority of white Americans to rally behind the draining of public resources and investments. Those very investments would provide white Americans — the largest group of the impoverished and uninsured — greater security, too: A new Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study  I grew up in one of those small Palestinian villages where some of Nimr’s readership likely stems from, quite close to where Nimr teaches. I read plenty of kid-lit on my way to school (and at school when I was supposed to be paying attention); I went on adventures with dragons and later, I traveled into deep space. I could have used a heroine like Qamar when I was younger to encourage me to step outside of my own reality. Not only does she look like me, Qamar feels written for me. I see much of my upbringing in Qamar, in how I approach rest, play, work, and curiosity, even perhaps how I approach being a woman. Qamar moves at her own pace, and while she is concerned with survival, she also understands how to adapt, when to let something bizarre and even unjust become normalized, and when that is no longer acceptable.

I grew up in one of those small Palestinian villages where some of Nimr’s readership likely stems from, quite close to where Nimr teaches. I read plenty of kid-lit on my way to school (and at school when I was supposed to be paying attention); I went on adventures with dragons and later, I traveled into deep space. I could have used a heroine like Qamar when I was younger to encourage me to step outside of my own reality. Not only does she look like me, Qamar feels written for me. I see much of my upbringing in Qamar, in how I approach rest, play, work, and curiosity, even perhaps how I approach being a woman. Qamar moves at her own pace, and while she is concerned with survival, she also understands how to adapt, when to let something bizarre and even unjust become normalized, and when that is no longer acceptable. We realize then that from the fantastic opening image of the sea whom the poet would like to invite in, like a good neighbor, to have a coffee, to the powerful ending of “All of It,” each line of Exhausted on the Cross is the scene of a physical fight, to the death, between words and what we can no longer say. We cannot express the tension of that centimeter that separates us from the woman from Shatila. There are no words to name the absolute horror, to account for the exact moment in which the body of a living child becomes the body of a slaughtered child, we lack images to fix that infinitesimal second in which someone becomes those lumps of flesh and bone thrown into the sea by Latin American dictators, or the heaps of scattered limbs of Palestinians crushed by Israeli bombs in Gaza, or those massacred in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. We have no concepts to imagine what questions, what memories assail someone in that monstrous extreme, someone being killed by other men. And yet, for that very reason, precisely because those words do not exist, they must be shouted, to bring to this side of the world the terrible and ruthless porosity of each of those moments.

We realize then that from the fantastic opening image of the sea whom the poet would like to invite in, like a good neighbor, to have a coffee, to the powerful ending of “All of It,” each line of Exhausted on the Cross is the scene of a physical fight, to the death, between words and what we can no longer say. We cannot express the tension of that centimeter that separates us from the woman from Shatila. There are no words to name the absolute horror, to account for the exact moment in which the body of a living child becomes the body of a slaughtered child, we lack images to fix that infinitesimal second in which someone becomes those lumps of flesh and bone thrown into the sea by Latin American dictators, or the heaps of scattered limbs of Palestinians crushed by Israeli bombs in Gaza, or those massacred in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. We have no concepts to imagine what questions, what memories assail someone in that monstrous extreme, someone being killed by other men. And yet, for that very reason, precisely because those words do not exist, they must be shouted, to bring to this side of the world the terrible and ruthless porosity of each of those moments. The names most associated with Black Lives Matter are not its leaders but the victims who have drawn attention to the massive issues of racism this country grapples with: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, to name a few. The movement can be traced back to 2013, after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot and killed Trayvon Martin in Florida. The 17-year-old had been returning from a shop after buying sweets and iced tea. Mr Zimmerman claimed the unarmed black teenager had looked suspicious. There was outrage when he was found not guilty of murder, and a Facebook post entitled “Black Lives Matter” captured a mood and sparked action.

The names most associated with Black Lives Matter are not its leaders but the victims who have drawn attention to the massive issues of racism this country grapples with: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, to name a few. The movement can be traced back to 2013, after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot and killed Trayvon Martin in Florida. The 17-year-old had been returning from a shop after buying sweets and iced tea. Mr Zimmerman claimed the unarmed black teenager had looked suspicious. There was outrage when he was found not guilty of murder, and a Facebook post entitled “Black Lives Matter” captured a mood and sparked action. ON MARCH 6,

ON MARCH 6, There are many kinds of pseudosciences: astrology, homeopathy, flat-Earthism, anti-vaxx. These ‘fields’ traffic in bizarre claims with scientific pretensions. On a surface level, these claims seem to be scientific and usually appear to comment on the same kind of things that science does. However, upon closer inspection, pseudoscience is revealed to be

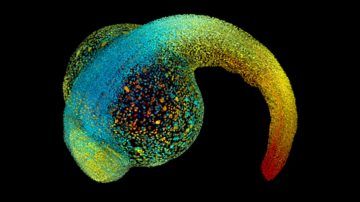

There are many kinds of pseudosciences: astrology, homeopathy, flat-Earthism, anti-vaxx. These ‘fields’ traffic in bizarre claims with scientific pretensions. On a surface level, these claims seem to be scientific and usually appear to comment on the same kind of things that science does. However, upon closer inspection, pseudoscience is revealed to be  At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain.

At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. First things first — much respect to Bill Gates for his membership in the select club of ultrabillionaires not actively attempting to flee Earth and colonize Mars. His affection for his home planet and the people on it shines through clearly in this new book, as does his proud and usually endearing geekiness. The book’s illustrations include photos of him inspecting industrial facilities, like a fertilizer distribution plant in Tanzania; definitely the happiest picture is of him and his son grinning identical grins outside an Icelandic geothermal power station. “Rory and I used to visit power plants for fun,” he writes, “just to learn how they worked.”

First things first — much respect to Bill Gates for his membership in the select club of ultrabillionaires not actively attempting to flee Earth and colonize Mars. His affection for his home planet and the people on it shines through clearly in this new book, as does his proud and usually endearing geekiness. The book’s illustrations include photos of him inspecting industrial facilities, like a fertilizer distribution plant in Tanzania; definitely the happiest picture is of him and his son grinning identical grins outside an Icelandic geothermal power station. “Rory and I used to visit power plants for fun,” he writes, “just to learn how they worked.” A consensus has emerged in recent years that psychotherapies—in particular, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—rate comparably to medications such as Prozac and Lexapro as treatments for depression. Either option, or the two together, may at times alleviate the mood disorder. In looking more closely at both treatments, CBT—which delves into dysfunctional thinking patterns—may have a benefit that could make it the better choice for a patient.

A consensus has emerged in recent years that psychotherapies—in particular, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—rate comparably to medications such as Prozac and Lexapro as treatments for depression. Either option, or the two together, may at times alleviate the mood disorder. In looking more closely at both treatments, CBT—which delves into dysfunctional thinking patterns—may have a benefit that could make it the better choice for a patient. When 22-year-old Cassius Clay

When 22-year-old Cassius Clay  “How did you reach adulthood without learning how to cook?”

“How did you reach adulthood without learning how to cook?” The history of digital cash consists of scientific discoveries from the 1970s, hardware from the 1980s, and networks from the 1990s, shaped by theories from the previous three centuries and beliefs about the next ten thousand years. It speaks ancient ideas with a modern twang, as we might when we say “quid pro quo” or “shibboleth”: the sovereign right to issue money, the debasement of coinage, the symbolic stamp that transfers the rights to value from me to thee. Digital cash has the hovering, unsettled realness (not reality) of all money, a matter of life and death that is also symbolic tokens, rules of a game, scraps of cotton blend and polymer, entries in a database, promises made and broken, gestures of affection and trust. The long history we are discussing here is at its heart the history of a debate about knowledge, an epistemological argument conducted through technologies.

The history of digital cash consists of scientific discoveries from the 1970s, hardware from the 1980s, and networks from the 1990s, shaped by theories from the previous three centuries and beliefs about the next ten thousand years. It speaks ancient ideas with a modern twang, as we might when we say “quid pro quo” or “shibboleth”: the sovereign right to issue money, the debasement of coinage, the symbolic stamp that transfers the rights to value from me to thee. Digital cash has the hovering, unsettled realness (not reality) of all money, a matter of life and death that is also symbolic tokens, rules of a game, scraps of cotton blend and polymer, entries in a database, promises made and broken, gestures of affection and trust. The long history we are discussing here is at its heart the history of a debate about knowledge, an epistemological argument conducted through technologies.