From 1843 Magazine:

The malevolence of cybercrime often seems all the worse for the impenetrable jargon used to describe attacks. Perhaps a “time bomb” blew up your computer, or malicious software turned your smartphone into a “zombie”? Even lower-tech crimes get strange labels: “shoulder-surfing” refers to when scammers nab your passwords by literally looking over your shoulder as you type (sometimes with binoculars). “Catfishing” is when you’re tricked into thinking you’re in an online relationship and unknowingly send cash to scammers using a fake profile (the supermodel who claims to have the hots for you may in fact be a 52-year-old man called Steve).

The malevolence of cybercrime often seems all the worse for the impenetrable jargon used to describe attacks. Perhaps a “time bomb” blew up your computer, or malicious software turned your smartphone into a “zombie”? Even lower-tech crimes get strange labels: “shoulder-surfing” refers to when scammers nab your passwords by literally looking over your shoulder as you type (sometimes with binoculars). “Catfishing” is when you’re tricked into thinking you’re in an online relationship and unknowingly send cash to scammers using a fake profile (the supermodel who claims to have the hots for you may in fact be a 52-year-old man called Steve).

Confusing you is exactly what these cyber-attackers want. And they’re worryingly successful: in America the amount of money lost to cybercrime increased threefold from 2015 to 2019. And that was before the pandemic pushed more criminals to focus on internet crime – just as many of us started living our entire lives online. Online criminals are often dubbed “hackers”. The term itself is controversial: many geeks use it to describe anyone with an advanced understanding of computers, and prefer the term “malicious hacker” for someone who uses their skills for nefarious purposes. They point out that hackers can also use their knowledge for good, to fight the bad guys. If you want to know the difference between online outlaws and angels, start by learning the language they speak.

More here.

THE CHARACTERS

THE CHARACTERS “Everybody” ’s central character is the Viennese psychoanalyst

“Everybody” ’s central character is the Viennese psychoanalyst  An insect’s brain is organised completely differently from a mammal’s. It is also

An insect’s brain is organised completely differently from a mammal’s. It is also  SARS-CoV-2 has caused a devastating global pandemic. The recent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants that are less sensitive to neutralization by convalescent sera or vaccine-induced neutralizing antibody responses has raised concerns. A second wave of SARS-CoV-2 infections in India is leading to the expansion of SARS-CoV-2 variants. The B.1.617.1 variant has rapidly spread throughout India and to several countries throughout the world. In this study, using a live virus assay, we describe the neutralizing antibody response to the B.1.617.1 variant in serum from infected and vaccinated individuals. We found that the B.1.617.1 variant is 6.8-fold more resistant to neutralization by sera from COVID-19 convalescent and Moderna and Pfizer vaccinated individuals. Despite this, a majority of the sera from convalescent individuals and all sera from vaccinated individuals were still able to neutralize the B.1.617.1 variant. This suggests that protective immunity by the mRNA vaccines tested here are likely retained against the B.1.617.1 variant. As the B.1.617.1 variant continues to evolve, it will be important to monitor how additional mutations within the spike impact antibody resistance, viral transmission and vaccine efficacy.

SARS-CoV-2 has caused a devastating global pandemic. The recent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants that are less sensitive to neutralization by convalescent sera or vaccine-induced neutralizing antibody responses has raised concerns. A second wave of SARS-CoV-2 infections in India is leading to the expansion of SARS-CoV-2 variants. The B.1.617.1 variant has rapidly spread throughout India and to several countries throughout the world. In this study, using a live virus assay, we describe the neutralizing antibody response to the B.1.617.1 variant in serum from infected and vaccinated individuals. We found that the B.1.617.1 variant is 6.8-fold more resistant to neutralization by sera from COVID-19 convalescent and Moderna and Pfizer vaccinated individuals. Despite this, a majority of the sera from convalescent individuals and all sera from vaccinated individuals were still able to neutralize the B.1.617.1 variant. This suggests that protective immunity by the mRNA vaccines tested here are likely retained against the B.1.617.1 variant. As the B.1.617.1 variant continues to evolve, it will be important to monitor how additional mutations within the spike impact antibody resistance, viral transmission and vaccine efficacy. The start of Joe Biden’s presidency has prompted an unlikely reassessment of the direction of American capitalism. Announcing a “paradigm shift” away from a policy regime that for decades has ruthlessly favored the very wealthy, Biden has invoked the New Deal to capture his vision for activist government. Alongside the expansion of the welfare state, he has promised an ambitious developmental agenda that links together infrastructure, industrial policy, and an energy transition to fight climate change. Though Biden’s resolve to execute his vision remains untested, the prospects for aggressive state intervention now seem far greater than during the Great Recession, when austerity quickly became a transatlantic phenomenon.

The start of Joe Biden’s presidency has prompted an unlikely reassessment of the direction of American capitalism. Announcing a “paradigm shift” away from a policy regime that for decades has ruthlessly favored the very wealthy, Biden has invoked the New Deal to capture his vision for activist government. Alongside the expansion of the welfare state, he has promised an ambitious developmental agenda that links together infrastructure, industrial policy, and an energy transition to fight climate change. Though Biden’s resolve to execute his vision remains untested, the prospects for aggressive state intervention now seem far greater than during the Great Recession, when austerity quickly became a transatlantic phenomenon. The sudden eruption of war outside and inside Israel’s borders has shocked a complacent nation. Throughout Binyamin Netanyahu’s 12-year premiership, the Palestinian problem was buried and forgotten. The recent Abraham Accords, establishing diplomatic relations with four Arab states, seemed to weaken the Palestinian cause further. Now it has re-emerged with a vengeance.

The sudden eruption of war outside and inside Israel’s borders has shocked a complacent nation. Throughout Binyamin Netanyahu’s 12-year premiership, the Palestinian problem was buried and forgotten. The recent Abraham Accords, establishing diplomatic relations with four Arab states, seemed to weaken the Palestinian cause further. Now it has re-emerged with a vengeance. Burnout is generally said to date to 1973; at least, that’s around when it got its name. By the nineteen-eighties, everyone was burned out. In 1990, when the Princeton scholar Robert Fagles published a new English translation of the Iliad, he had Achilles tell Agamemnon that he doesn’t want people to think he’s “a worthless, burnt-out coward.” This expression, needless to say, was not in Homer’s original Greek. Still, the notion that people who fought in the Trojan War, in the twelfth or thirteenth century B.C., suffered from burnout is a good indication of the disorder’s claim to universality: people who write about burnout tend to argue that it exists everywhere and has existed forever, even if, somehow, it’s always getting worse. One Swiss psychotherapist, in a history of burnout published in 2013 that begins with the usual invocation of immediate emergency—“Burnout is increasingly serious and of widespread concern”—insists that he found it in the Old Testament. Moses was burned out, in Numbers 11:14, when he complained to God, “I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me.” And so was Elijah, in 1 Kings 19, when he “went a day’s journey into the wilderness, and came and sat down under a juniper tree: and he requested for himself that he might die; and said, It is enough.”

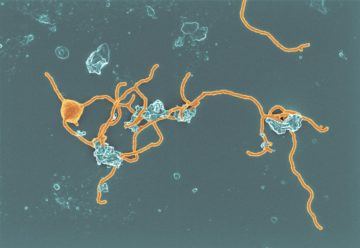

Burnout is generally said to date to 1973; at least, that’s around when it got its name. By the nineteen-eighties, everyone was burned out. In 1990, when the Princeton scholar Robert Fagles published a new English translation of the Iliad, he had Achilles tell Agamemnon that he doesn’t want people to think he’s “a worthless, burnt-out coward.” This expression, needless to say, was not in Homer’s original Greek. Still, the notion that people who fought in the Trojan War, in the twelfth or thirteenth century B.C., suffered from burnout is a good indication of the disorder’s claim to universality: people who write about burnout tend to argue that it exists everywhere and has existed forever, even if, somehow, it’s always getting worse. One Swiss psychotherapist, in a history of burnout published in 2013 that begins with the usual invocation of immediate emergency—“Burnout is increasingly serious and of widespread concern”—insists that he found it in the Old Testament. Moses was burned out, in Numbers 11:14, when he complained to God, “I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me.” And so was Elijah, in 1 Kings 19, when he “went a day’s journey into the wilderness, and came and sat down under a juniper tree: and he requested for himself that he might die; and said, It is enough.” Evolutionary biologist David Baum was thrilled to flick through a preprint in August 2019 and come face-to-face — well, face-to-cell — with a distant cousin. Baum, who works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, was looking at an archaeon: a type of microorganism best known for living in extreme environments, such as deep-ocean vents and acid lakes. Archaea can look similar to bacteria, but have about as much in common with them as they do with a banana. The one in the bioRxiv preprint had tentacle-like projections, making the cells look like meatballs with some strands of spaghetti attached. Baum had spent a lot of time imagining what humans’ far-flung ancestors might look like, and this microbe was a perfect doppelgänger.

Evolutionary biologist David Baum was thrilled to flick through a preprint in August 2019 and come face-to-face — well, face-to-cell — with a distant cousin. Baum, who works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, was looking at an archaeon: a type of microorganism best known for living in extreme environments, such as deep-ocean vents and acid lakes. Archaea can look similar to bacteria, but have about as much in common with them as they do with a banana. The one in the bioRxiv preprint had tentacle-like projections, making the cells look like meatballs with some strands of spaghetti attached. Baum had spent a lot of time imagining what humans’ far-flung ancestors might look like, and this microbe was a perfect doppelgänger. “Ethnoscience” and “Indigenous science”, along with more fine-grained designations like “ethnomathematics”, “ethnoastronomy”, etc., are common terms used to describe both Indigenous systems of knowledge, as well as the scholarly study of these systems. These terms are contested among specialists, for reasons I will not address here. More recently they have also been swallowed up by the voracious beast that is our neverending culture war, and are now hotly contested by people who know nothing about them as well.

“Ethnoscience” and “Indigenous science”, along with more fine-grained designations like “ethnomathematics”, “ethnoastronomy”, etc., are common terms used to describe both Indigenous systems of knowledge, as well as the scholarly study of these systems. These terms are contested among specialists, for reasons I will not address here. More recently they have also been swallowed up by the voracious beast that is our neverending culture war, and are now hotly contested by people who know nothing about them as well. For as much as people talk about food, a good case can be made that we don’t give it the attention or respect it actually deserves. Food is central to human life, and how we go about the process of creating and consuming it — from agriculture to distribution to cooking to dining — touches the most mundane aspects of our daily routines as well as large-scale questions of geopolitics and culture. Rachel Laudan is a historian of science whose masterful book,

For as much as people talk about food, a good case can be made that we don’t give it the attention or respect it actually deserves. Food is central to human life, and how we go about the process of creating and consuming it — from agriculture to distribution to cooking to dining — touches the most mundane aspects of our daily routines as well as large-scale questions of geopolitics and culture. Rachel Laudan is a historian of science whose masterful book,  Could you define what you mean by “noise” in the book, in layman’s terms – how does it differ from things like subjectivity or error?

Could you define what you mean by “noise” in the book, in layman’s terms – how does it differ from things like subjectivity or error? P

P For centuries, humans have been captivated by the beauty of the betta. Their slender bodies and oversized fins, which hang like bolts of silk, come in a variety of vibrant colors seldom seen in nature. However, bettas, also known as the Siamese fighting fish, did not become living works of art on their own. The betta’s elaborate colors and long, flowing fins are the product of a millennium of careful selective breeding. Or as Yi-Kai Tea, a doctoral candidate at the University of Sydney who studies the evolution and speciation of fishes, put it, “quite literally the fish equivalent of dog domestication.”

For centuries, humans have been captivated by the beauty of the betta. Their slender bodies and oversized fins, which hang like bolts of silk, come in a variety of vibrant colors seldom seen in nature. However, bettas, also known as the Siamese fighting fish, did not become living works of art on their own. The betta’s elaborate colors and long, flowing fins are the product of a millennium of careful selective breeding. Or as Yi-Kai Tea, a doctoral candidate at the University of Sydney who studies the evolution and speciation of fishes, put it, “quite literally the fish equivalent of dog domestication.” Along a dried-up channel of the Euphrates river in modern-day Iraq, broken mud bricks poke out of vast, dusty ruins. They are the remains of Uruk, the birthplace of writing that’s better known in popular culture today as the city once ruled by the legendary king Gilgamesh, the hero of an epic about his struggle with life, love and death. Sometimes called the oldest story in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh continues to resonate with modern audiences more than

Along a dried-up channel of the Euphrates river in modern-day Iraq, broken mud bricks poke out of vast, dusty ruins. They are the remains of Uruk, the birthplace of writing that’s better known in popular culture today as the city once ruled by the legendary king Gilgamesh, the hero of an epic about his struggle with life, love and death. Sometimes called the oldest story in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh continues to resonate with modern audiences more than