George Scialabba in The Baffler:

George Scialabba in The Baffler:

AT THE END OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, the United States, with 6 percent of the world’s population, accounted for 50 percent of the world’s production. Militarily, it was invulnerable: it controlled both oceans and had sole possession of the most fearsome weapon ever invented. Culturally, American movies and popular music were all-conquering. Perhaps most important was America’s moral standing. Woodrow Wilson’s (not entirely deserved) reputation as an apostle of self-determination; the United States’ apparent lack of territorial ambition; and the awful fate from which the U.S. and the USSR had saved Europe—all aroused hopes for America’s moral leadership. Those hopes seemed to find fulfillment in the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as wise and generous a scheme for international order as any yet devised. But the UN, along with America’s moral prestige, fell victim to the superpower rivalry that extended from 1945 to 1991 and is known as the Cold War.

That is not the story Louis Menand aims to tell in his teeming and colorful history of “art and thought in the Cold War.” Helpfully, Menand explains that this is “not a book about the ‘cultural Cold War’ (the use of cultural diplomacy as an instrument of foreign policy).” Nor is it a book about “‘Cold War culture’ (art and ideas as reflections of Cold War ideology and conditions).” (A good example of the former is Frances Stonor Saunders’s The Cultural Cold War; of the latter, Duncan White’s Cold Warriors.) The Free World is intellectual history, primarily a narrative of ideas talking to ideas and works of art talking to works of art, while also trying to take into account “the underlying social forces—economic, geopolitical, demographic, technological—that created the conditions for the possibility of certain kinds of art and ideas.”

More here.

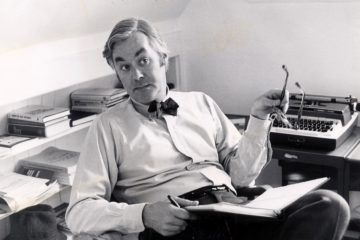

“The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society,” Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York said during a lecture at Harvard in 1986. “The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself.” Moynihan, an apostle of complexity, lived at the intersection of those two truths, a place where he was free to become one of the most creative American thinkers of the late 20th century. He sensed, and then came to know, that the social problems of what was being called “postindustrial” society would be different from those that came before. He identified these problems, sometimes controversially. In so doing, he predicted the dislocations of the 21st century with uncanny accuracy. He did it with elegance and wit and — this may be a surprise — transcendent humility. His spot-on sense of what truly mattered deserves to be revisited now, if we’re to grope our way past the mess we’ve become as a society.

“The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society,” Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York said during a lecture at Harvard in 1986. “The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself.” Moynihan, an apostle of complexity, lived at the intersection of those two truths, a place where he was free to become one of the most creative American thinkers of the late 20th century. He sensed, and then came to know, that the social problems of what was being called “postindustrial” society would be different from those that came before. He identified these problems, sometimes controversially. In so doing, he predicted the dislocations of the 21st century with uncanny accuracy. He did it with elegance and wit and — this may be a surprise — transcendent humility. His spot-on sense of what truly mattered deserves to be revisited now, if we’re to grope our way past the mess we’ve become as a society.

This time last year, the United States seemed stuck on a COVID-19 plateau. Although 1,300 Americans were dying from the disease every day, states had begun to reopen in

This time last year, the United States seemed stuck on a COVID-19 plateau. Although 1,300 Americans were dying from the disease every day, states had begun to reopen in  Last Saturday was Nakba Day, which commemorates the 700,000 Palestinians who were expelled by Israel – or who fled in fear – during the country’s founding in 1948. The commemoration had special resonance this year, since it was Israel’s impending expulsion of six Palestinian families from the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah that

Last Saturday was Nakba Day, which commemorates the 700,000 Palestinians who were expelled by Israel – or who fled in fear – during the country’s founding in 1948. The commemoration had special resonance this year, since it was Israel’s impending expulsion of six Palestinian families from the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah that  I would imagine that anyone approaching Edmund Gordon’s comprehensive biography, The Invention of Angela Carter, has a memorable “first time” with Carter. When it comes to cult figures of the intelligentsia, the story of the first time is practically de rigueur. Gordon himself mentions his own in his epilogue. During a post-university year in Berlin, he came upon a secondhand copy of The Magic Toyshop, which Carter had described to her editor in 1966 as a “Gothic melodrama about a sort of South Suburban bluebeard toymaker & his household.” A writer Gordon admired, Ali Smith (an iconoclast of her own order), had spoken highly of Carter, whose reputation he’d previously thought had something “off-putting” about it—“a sense, perhaps, that she was just for girls.” Nonetheless, he bought the novel and “tore” through it “in a few intoxicated hours, stunned by the fearless quality of the imagination on display and by the luminous beauty of the prose.”

I would imagine that anyone approaching Edmund Gordon’s comprehensive biography, The Invention of Angela Carter, has a memorable “first time” with Carter. When it comes to cult figures of the intelligentsia, the story of the first time is practically de rigueur. Gordon himself mentions his own in his epilogue. During a post-university year in Berlin, he came upon a secondhand copy of The Magic Toyshop, which Carter had described to her editor in 1966 as a “Gothic melodrama about a sort of South Suburban bluebeard toymaker & his household.” A writer Gordon admired, Ali Smith (an iconoclast of her own order), had spoken highly of Carter, whose reputation he’d previously thought had something “off-putting” about it—“a sense, perhaps, that she was just for girls.” Nonetheless, he bought the novel and “tore” through it “in a few intoxicated hours, stunned by the fearless quality of the imagination on display and by the luminous beauty of the prose.” As a tormented young anarchist pacifist pining for radical deliverance while cooped up at home with his parents in Berlin during the First World War, Gershom Scholem felt absolutely committed to one cause: Zionism. The only problem, he acknowledged in his journal, was that Zionists had not yet defined the contents of their ideology. As far as Scholem was concerned, Zionism had no political implications. It did not necessitate an oceanic ingathering of the Jewish people from the diaspora. There was no imperative to farm the Holy Land. The movement, in the eyes of the future pioneering scholar of kabbalah, was a humanistic, anti-bourgeois endeavour that probably required a commitment to living in Palestine or thereabouts. But it did not require the acquisition of sovereign control over territory, let alone taking possession of land belonging to the Arab peoples resident in the country.

As a tormented young anarchist pacifist pining for radical deliverance while cooped up at home with his parents in Berlin during the First World War, Gershom Scholem felt absolutely committed to one cause: Zionism. The only problem, he acknowledged in his journal, was that Zionists had not yet defined the contents of their ideology. As far as Scholem was concerned, Zionism had no political implications. It did not necessitate an oceanic ingathering of the Jewish people from the diaspora. There was no imperative to farm the Holy Land. The movement, in the eyes of the future pioneering scholar of kabbalah, was a humanistic, anti-bourgeois endeavour that probably required a commitment to living in Palestine or thereabouts. But it did not require the acquisition of sovereign control over territory, let alone taking possession of land belonging to the Arab peoples resident in the country. Leading Indian authors Pankaj Mishra and

Leading Indian authors Pankaj Mishra and  Since the modern era of research on autism began in the 1980s, questions about social cognition and social brain development have been of central interest to researchers. This year marks the 20th anniversary of the first annual meeting of the

Since the modern era of research on autism began in the 1980s, questions about social cognition and social brain development have been of central interest to researchers. This year marks the 20th anniversary of the first annual meeting of the  It’s hard to understand the culture of policing in America from the outside.

It’s hard to understand the culture of policing in America from the outside. One pillar of the modern world was the project to transform science from a discipline for contemplating nature into a tool for mastering it. Queen among the new sciences was mathematical physics, made possible by a corresponding transformation of mathematics. Ancient mathematicians, said René Descartes, had misunderstood their subject. They offered a procession of dazzling spectacles, but mathematics properly understood is not the presentation of beautiful chance discoveries. It must instead provide a systematic method for solving problems.

One pillar of the modern world was the project to transform science from a discipline for contemplating nature into a tool for mastering it. Queen among the new sciences was mathematical physics, made possible by a corresponding transformation of mathematics. Ancient mathematicians, said René Descartes, had misunderstood their subject. They offered a procession of dazzling spectacles, but mathematics properly understood is not the presentation of beautiful chance discoveries. It must instead provide a systematic method for solving problems. In a study of the effectiveness of putting calorie counts on menu items, consumers were more likely to make lower-calorie choices if the labels were placed to the left of the food item rather than the right.

In a study of the effectiveness of putting calorie counts on menu items, consumers were more likely to make lower-calorie choices if the labels were placed to the left of the food item rather than the right. France’s literary institutions have long struggled with a diversity problem. Though France doesn’t collect statistics on race and ethnicity, a majority of top editors and authors have historically been white. Its literary awards heavily favor men: Since France’s top literature prize, the Prix Goncourt, began in 1903, only 12 women have won. The integration of marginalized literary voices, especially those of second-generation French or people of color, has come in fits and starts. Until the 1990s, literature written by children of immigrant parents of Maghrebis descent was categorized using a pejorative term for Arab. The publication of a 1999 novel by Rachid Djaïdani, which described daily life in France’s housing projects where many immigrants live, was a landmark in breaking the mold. Another was the publication in 2007 of a controversial literary collection by second-generation French writers about their complex relationship with France.

France’s literary institutions have long struggled with a diversity problem. Though France doesn’t collect statistics on race and ethnicity, a majority of top editors and authors have historically been white. Its literary awards heavily favor men: Since France’s top literature prize, the Prix Goncourt, began in 1903, only 12 women have won. The integration of marginalized literary voices, especially those of second-generation French or people of color, has come in fits and starts. Until the 1990s, literature written by children of immigrant parents of Maghrebis descent was categorized using a pejorative term for Arab. The publication of a 1999 novel by Rachid Djaïdani, which described daily life in France’s housing projects where many immigrants live, was a landmark in breaking the mold. Another was the publication in 2007 of a controversial literary collection by second-generation French writers about their complex relationship with France. T

T