https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wTkU4tP38Cw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wTkU4tP38Cw

Maura O’Kiely at the Dublin Review of Books:

Wait, not another book about the Beatles? Surely that story’s bones have been picked clean by now? What saves One Two Three Four from being just another Beatles indulgathon is how the author has reworked the standard biography template. His take is a seductive miscellany of essays, insider accounts, opinions, flight-of-fancy yarns, and more. Much of it is sourced from already published material but Brown also includes his own opinions and anecdotes. Somehow he has managed to create a uniquely fresh perceptive on a well-worn story.

Wait, not another book about the Beatles? Surely that story’s bones have been picked clean by now? What saves One Two Three Four from being just another Beatles indulgathon is how the author has reworked the standard biography template. His take is a seductive miscellany of essays, insider accounts, opinions, flight-of-fancy yarns, and more. Much of it is sourced from already published material but Brown also includes his own opinions and anecdotes. Somehow he has managed to create a uniquely fresh perceptive on a well-worn story.

In 1961, when that first meeting with Epstein takes place, the Beatles are four talented youngsters high on nothing more psychedelic than Starbursts, larking about in the Cavern. The lightning celerity of their ascent to the top of Mount Fame still astonishes. By 1962, they have a number one hit in Britain. The following year, as if operating on fast-forward, they hold the top five places on America’s Billboard chart.

more here.

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

“FILING FOR DIVORCE,” a family lawyer once told me, “is like pulling the thread from a seam . . . everything that was contained within falls out.” In the unraveling of the marriage of Bill and Melinda Gates, who announced their plan to divorce a few weeks ago, the noxious innards are now falling out. On May 16, more details emerged about nerdy and soon-to-be-single Mr. Gates’s friendship with the convicted and now dead sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. The Daily Beast reports that a disgruntled Gates used Epstein’s Manhattan home as an escape from his “toxic” but then still intact marriage numerous times between 2011 and 2014. Epstein was for Gates the buddy who hears your complaints about married life and tells you to call it quits. For his part, Gates reportedly told Epstein to repair his own reputation—to put that 2008 guilty plea for solicitation of sex with a minor in the past. The fact that his bachelor buddy was involved—even then—in such nefarious acts appeared not to be a concern to Gates. By 2019, shortly after Epstein was found dead, Gates tried to explain away the relationship, telling the Wall Street Journal, “I met him. I didn’t have any business relationship or friendship with him.”

“FILING FOR DIVORCE,” a family lawyer once told me, “is like pulling the thread from a seam . . . everything that was contained within falls out.” In the unraveling of the marriage of Bill and Melinda Gates, who announced their plan to divorce a few weeks ago, the noxious innards are now falling out. On May 16, more details emerged about nerdy and soon-to-be-single Mr. Gates’s friendship with the convicted and now dead sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. The Daily Beast reports that a disgruntled Gates used Epstein’s Manhattan home as an escape from his “toxic” but then still intact marriage numerous times between 2011 and 2014. Epstein was for Gates the buddy who hears your complaints about married life and tells you to call it quits. For his part, Gates reportedly told Epstein to repair his own reputation—to put that 2008 guilty plea for solicitation of sex with a minor in the past. The fact that his bachelor buddy was involved—even then—in such nefarious acts appeared not to be a concern to Gates. By 2019, shortly after Epstein was found dead, Gates tried to explain away the relationship, telling the Wall Street Journal, “I met him. I didn’t have any business relationship or friendship with him.”

As sources presumably connected to Melinda are telling it now, it was Bill’s friendship with Epstein, added to his history of allegedly harassing female employees at Microsoft (he stepped down from the board after an investigation into such allegations), that prompted her to consider divorce. She is reported to have started conversations with lawyers about filing for divorce in 2019, although she was aware of Bill’s meetings with Epstein at least as far back as 2013.

With that knowledge, Melinda French Gates was in a difficult position. In the meantime, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation chugged along in the business of saving the world. The Annual Bill and Melinda Gates letters went out, signed as before by the two of them. Notably, the 2021 letter does not show the couple together but sitting at their own work-from-home stations, presumably still saving the world from home. There is Bill Gates the billionaire in a magenta sweater, staring deep into his screen as he considers the world’s thorny problems, with little time to sort out the couple’s irreconcilable differences.

More here.

Nidhi Subbaraman in Nature:

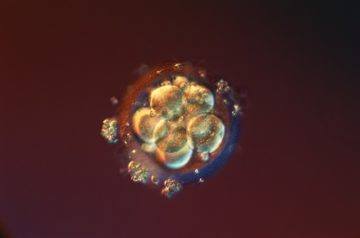

The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped.

The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped.

The ISSCR made this change and others to its guidelines for biomedical research in response to rapid advances in the field, including the ability to create embryo-like structures from human stem cells. In addition to relaxing the ‘14-day rule’, for instance, the group advises against editing genes in human embryos until the safety of genome editing is better established.

More here.

about splitting

inevitable tiny laugh

oh it’s not so bad

your body was built

for this. we have mothered

for centuries. i gesture

to the line of women

behind me. my great

great grandmother

died giving light

my other great

great grandmother

gave light and lived

but not willingly

and that is death too

my other other

great great grandmother

drank (my grandfather

her son was the little boy

retrieving his sleeping mother

from the velvet kentucky

lounges) and my other

other other great great

grandmother i know nothing

of her. all i have

is a picture of a woman

seated, her hands braided

black hair meticulous

middle parted, a face

like medicine, a face

that says I have always been

i am this last woman’s namesake

estefania, meaning – a crown

a garland. that which surrounds or

encircles. the first martyr

a man i love enters the poem

and asks me to put the picture away

she upends him

she upends me too

i tuck her into a tiny

corner of myself

by Estefania Stout Larios

from The Rumpus, 5/27/21

Alex Dean in Prospect:

George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick.

George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick.

Yet Berkeley is also widely misunderstood. Different aspects of his thinking, not to mention his character, seem to clash quite spectacularly. His most famous doctrine was viewed as heretical in its day, yet Berkeley was a bishop and fierce believer in the supremacy of the Anglican church. He simultaneously advanced radically counter-intuitive and staunchly conservative arguments. He was a passionate social reformer but was complicit in appalling social evils. This makes Berkeley a fascinating subject. He appears a study in contradiction—but stick with him long enough and you realise that maybe there is no contradiction at all.

More here.

Elias Rodriquez at The Nation:

A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s.

A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s.

more here.

Jeff Wall at nonsite:

I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think.

I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think.

The critiques were aimed at all the traditional art forms, not just painting, but the debate has focused on painting more than on sculpture, even though the same claims have been made for both arts.

I’ll reiterate those claims, as briefly as I can (and I apologize in advance if its not brief enough). They’ve been elaborated over a long historical period, beginning probably with Vasari and concluding, or being substantially interrupted, in the 1970s.

more here.

Eric Boodman in Stat News:

One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.

One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.

What was surprising was that the first invited speaker had chosen to frame himself as an authority on Covid-19 at all. His name was Michael Levitt. His credentials were stellar — an endowed Stanford professorship, one-third of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry — but utterly unrelated to infectious disease outbreaks. He’d won his honors with the computer-programming work he’d done in the 1960s and 70s, revealing the intricate origami of proteins, modeling how they fold and form the tiny machinery of life. Prior to those papers, the chair of the Nobel selection committee had said, studying chemical reactions was “like seeing all the actors before Hamlet and all the dead bodies after, and then you wonder what happened in the middle.” Levitt and his colleagues had described “the whole drama,” showing how each character died.

Now, though, dead bodies weren’t a metaphor. They were horrifyingly literal, their bagged bulk filling hospital morgues and refrigerated trucks. Public health specialists begged politicians and citizens to do what they could to slow transmission. Levitt, a biophysicist, had different ideas. He derided policies proposed by the vast majority of epidemiologists as “politically correct.”

More here.

Yanis Varoufakis in Project Syndicate:

Back in the 1830s, Thomas Peel decided to migrate from England to Swan River in Western Australia. A man of means, Peel took along, besides his family, “300 persons of the working class, men, women, and children,” as well as “means of subsistence and production to the amount of £50,000.” But soon after arrival, Peel’s plans were in ruins.

The cause was not disease, disaster, or bad soil. Peel’s labor force abandoned him, got themselves plots of land in the surrounding wilderness, and went into “business” for themselves. Although Peel had brought labor, money, and physical capital with him, the workers’ access to alternatives meant that he could not bring capitalism.

Karl Marx recounted Peel’s story in Capital, Volume I to make the point that “capital is not a thing, but a social relation between persons.” The parable remains useful today in illuminating not only the difference between money and capital, but also why austerity, despite its illogicality, keeps coming back.

More here.

—for my sister

Howard LaFranchi in The Christian Science Monitor:

For decades, the Democratic Party has stood by Israel in times of war and peace.

For decades, the Democratic Party has stood by Israel in times of war and peace.

Today, that support no longer looks so solid. In the Democratic-controlled Congress, more lawmakers are calling out Israel for its actions in its latest conflict with Hamas that ended in a cease-fire last week. And this poses a dilemma for President Joe Biden, a staunch ally of Israel who has vowed to make human rights a priority, not an afterthought in his administration. On May 15, after the U.S. blocked United Nations efforts to seek a cease-fire in Gaza, where Israeli airstrikes had leveled residential buildings in retaliation for Hamas rockets, New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democrat, issued a caustic tweet. “If the Biden administration can’t stand up to an ally,” meaning Israel, “who can it stand up to? How can they credibly claim to stand for human rights?”

Ms. Ocasio-Cortez and other Democratic critics say the United States looks hypocritical for standing unwaveringly by Israel even as it took actions in Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Hamas-controlled Gaza that a mounting international chorus condemned as gross violations of Palestinian rights. And it’s not just firebrands in Congress who are challenging Mr. Biden to steer away from a traditional “Israel first and unquestioned” approach to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and toward a more nuanced and balanced approach that puts human rights at the fore.

Democratic Sen. Bob Menendez of New Jersey, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a longtime staunch Israel supporter, issued a statement on the same day as Ms. Ocasio-Cortez’s tweet. He called out Israel for “the death of innocent civilians” and for targeting a Gaza high-rise in which international media outlets had offices. Taken together, this amounts to a wake-up call for the White House that the Democratic Party has now shifted on how it sees the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the U.S. role in addressing it.

More here.

From Phys.Org:

![]() Army ants form some of the largest insect societies on the planet. They are quite famous in popular culture, most notably from a terrifying scene in Indiana Jones. But they are also ecologically important. They live in very large colonies and consume large amounts of arthropods. And because they eat so much of the other animals around them, they are nomadic and must keep moving in order to not run out of food. Due to their nomadic nature and mass consumption of food, they have a huge impact on arthropod populations throughout tropical rainforests floors.

Army ants form some of the largest insect societies on the planet. They are quite famous in popular culture, most notably from a terrifying scene in Indiana Jones. But they are also ecologically important. They live in very large colonies and consume large amounts of arthropods. And because they eat so much of the other animals around them, they are nomadic and must keep moving in order to not run out of food. Due to their nomadic nature and mass consumption of food, they have a huge impact on arthropod populations throughout tropical rainforests floors.

Their mass raids are considered the pinnacle of collective foraging behavior in the animal kingdom. The raids are a coordinated hunting swarm of thousands and, in some species, millions of ants. The ants spontaneously stream out of their nest, moving across the forest floor in columns to hunt for food. The raids are one of the most iconic collective behaviors in the animal kingdom. Scientists have studied their ecology and observed their complex behavior extensively. And while we know how these raids happen, we know nothing of how they evolved.

A new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences led by Vikram Chandra, postdoctoral researcher, Harvard University, Asaf Gal, postdoctoral fellow, The Rockefeller University, and Daniel J.C. Kronauer, Stanley S. and Sydney R. Shuman Associate Professor, The Rockefeller University, combines phylogenetic reconstructions and computational behavioral analysis to show that army ant mass raiding evolved from a different form of coordinated hunting called group raiding through the scaling effects of increasing colony size.

More here.

Salman Rushdie in the New York Times:

I believe that the books and stories we fall in love with make us who we are, or, not to claim too much, the beloved tale becomes a part of the way in which we understand things and make judgments and choices in our daily lives. A book may cease to speak to us as we grow older, and our feeling for it will fade. Or we may suddenly, as our lives shape and hopefully increase our understanding, be able to appreciate a book we dismissed earlier; we may suddenly be able to hear its music, to be enraptured by its song.

I believe that the books and stories we fall in love with make us who we are, or, not to claim too much, the beloved tale becomes a part of the way in which we understand things and make judgments and choices in our daily lives. A book may cease to speak to us as we grow older, and our feeling for it will fade. Or we may suddenly, as our lives shape and hopefully increase our understanding, be able to appreciate a book we dismissed earlier; we may suddenly be able to hear its music, to be enraptured by its song.

When, as a college student, I first read Günter Grass’s great novel “The Tin Drum,” I was unable to finish it. It languished on a shelf for fully 10 years before I gave it a second chance, whereupon it became one of my favorite novels of all time: one of the books I would say that I love. It is an interesting question to ask oneself: Which are the books that you truly love? Try it. The answer will tell you a lot about who you presently are.

More here.

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Democracy posits the radical idea that political power and legitimacy should ultimately be found in all of the people, rather than a small group of experts or for that matter arbitrarily-chosen hereditary dynasties. Nevertheless, a good case can be made that the bottom-up and experimental nature of democracy actually makes for better problem-solving in the political arena than other systems. Political theorist Henry Farrell (in collaboration with statistician Cosma Shalizi) has made exactly that case. We discuss the general idea of solving social problems, and compare different kinds of macro-institutions — markets, hierarchies, and democracies — to ask whether democracies aren’t merely politically just, but also an efficient way of generating good ideas.

Democracy posits the radical idea that political power and legitimacy should ultimately be found in all of the people, rather than a small group of experts or for that matter arbitrarily-chosen hereditary dynasties. Nevertheless, a good case can be made that the bottom-up and experimental nature of democracy actually makes for better problem-solving in the political arena than other systems. Political theorist Henry Farrell (in collaboration with statistician Cosma Shalizi) has made exactly that case. We discuss the general idea of solving social problems, and compare different kinds of macro-institutions — markets, hierarchies, and democracies — to ask whether democracies aren’t merely politically just, but also an efficient way of generating good ideas.

More here.

Rana Mitter and Elsbeth Johnson in the Harvard Business Review:

When we first traveled to China, in the early 1990s, it was very different from what we see today. Even in Beijing many people wore Mao suits and cycled everywhere; only senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials used cars. In the countryside life retained many of its traditional elements. But over the next 30 years, thanks to policies aimed at developing the economy and increasing capital investment, China emerged as a global power, with the second-largest economy in the world and a burgeoning middle class eager to spend.

When we first traveled to China, in the early 1990s, it was very different from what we see today. Even in Beijing many people wore Mao suits and cycled everywhere; only senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials used cars. In the countryside life retained many of its traditional elements. But over the next 30 years, thanks to policies aimed at developing the economy and increasing capital investment, China emerged as a global power, with the second-largest economy in the world and a burgeoning middle class eager to spend.

One thing hasn’t changed, though: Many Western politicians and business executives still don’t get China. Believing, for example, that political freedom would follow the new economic freedoms, they wrongly assumed that China’s internet would be similar to the freewheeling and often politically disruptive version developed in the West. And believing that China’s economic growth would have to be built on the same foundations as those in the West, many failed to envisage the Chinese state’s continuing role as investor, regulator, and intellectual property owner.

Why do leaders in the West persist in getting China so wrong?

More here.

Simon Parkin at The Guardian:

Along with fish, aluminium and Björk, Eve Online is one of Iceland’s biggest exports. Launched in 2003, it is a science-fiction project of unprecedented scale and ambition. It presents a cosmos of 7,500 interconnected star systems, known as New Eden, which can be travelled in spaceships built and flown by any individual. In-game professions vary. There are miners, traders, pirates, journalists and educators. You are free to work alone or in loose-knit corporations and alliances, the largest of which are comprised of tens of thousands of members.

Along with fish, aluminium and Björk, Eve Online is one of Iceland’s biggest exports. Launched in 2003, it is a science-fiction project of unprecedented scale and ambition. It presents a cosmos of 7,500 interconnected star systems, known as New Eden, which can be travelled in spaceships built and flown by any individual. In-game professions vary. There are miners, traders, pirates, journalists and educators. You are free to work alone or in loose-knit corporations and alliances, the largest of which are comprised of tens of thousands of members.

As a microcosm of human activity, the game has been studied by academics interested in creating political models, and by economists interested in testing financial ones. In a universe where every bullet, trade, offer of friendship and betrayal can be tracked and its impact logged and measured, Eve offers a new way to understand our species and the social systems of our world.

more here.

The Center for Land Use Interpretation at Cabinet Magazine:

The American Land Museum is a network of landscape exhibition sites being developed across the United States by the Center for Land Use Interpretation and other agencies. The purpose of the museum is to create a dynamic contemporary portrait of the nation, a portrait composed of the national landscape itself. Selected exhibition locations represent regional land use patterns, themes, and development issues. Within each exhibit location are a number of specified experiential zones with collections of material artifacts in the landscape, landmarks selected from among the field of existing structures.

The American Land Museum is a network of landscape exhibition sites being developed across the United States by the Center for Land Use Interpretation and other agencies. The purpose of the museum is to create a dynamic contemporary portrait of the nation, a portrait composed of the national landscape itself. Selected exhibition locations represent regional land use patterns, themes, and development issues. Within each exhibit location are a number of specified experiential zones with collections of material artifacts in the landscape, landmarks selected from among the field of existing structures.

Wendover, Utah, is the American Land Museum’s regional location in the Great Basin. Beyond the Museum’s Information Center, exhibits can be found among the waste disposal industries, explosives plants, survivability training sites, and weapons test areas that have developed within this broad, geomorphologically self-contained region.

more here.