Hatty Nestor at Granta:

Society loves courtroom dramas – they allow the viewer to consume the uncertainty of someone else’s life as opposed to fixating on their own. (I am as guilty of this as anyone: I’ve watched courtroom dramas every week religiously in the past, especially Primal Fear and The Lincoln Lawyer.) We get hooked on the interrelations of characters, the impending catastrophe, the emotional mind games played by the press, lawyers, and bogeymen criminals. The allure of the genre, I believe, has to do with the hidden nature of the legal scenario. Films, television shows, and podcasts purport to expose the mystery of the courtroom, and the private lives of those tangled up in its web.

Society loves courtroom dramas – they allow the viewer to consume the uncertainty of someone else’s life as opposed to fixating on their own. (I am as guilty of this as anyone: I’ve watched courtroom dramas every week religiously in the past, especially Primal Fear and The Lincoln Lawyer.) We get hooked on the interrelations of characters, the impending catastrophe, the emotional mind games played by the press, lawyers, and bogeymen criminals. The allure of the genre, I believe, has to do with the hidden nature of the legal scenario. Films, television shows, and podcasts purport to expose the mystery of the courtroom, and the private lives of those tangled up in its web.

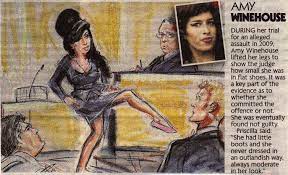

Beyond courtroom dramas and ‘true crime’ stories of trials, such as Dateline, American Crime Story, Killing Fields, and my recent favourite, Netflix’s The Staircase, the courtroom sketch is a key example of how the goings-on at trial are represented and disseminated. Notable cases that have been illustrated include Amy Winehouse’s 2009 trial for assault after she was accused of hitting a woman at a charity ball. A drawing by sketch artist Priscilla Coleman shows Winehouse extending her leg and hitching up her dress, in order to demonstrate to the court her slight frame as evidence of her innocence.

more here.

“Creep” was subsequently excised from the band’s set list

“Creep” was subsequently excised from the band’s set list  For more than a year now, scientists and clinicians have been trying to understand why some people develop severe COVID-19 whereas others barely show any symptoms. Risk factors such as age and underlying medical conditions

For more than a year now, scientists and clinicians have been trying to understand why some people develop severe COVID-19 whereas others barely show any symptoms. Risk factors such as age and underlying medical conditions Thirty years ago, Albert O Hirschman published a short book that infuriated conservatives called

Thirty years ago, Albert O Hirschman published a short book that infuriated conservatives called  O

O My father, a neurologist, once had a patient who was tormented, in the most visceral sense, by a poem. Philip was 12 years old and a student at a prestigious boarding school in Princeton, New Jersey. One of his assignments was to recite Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. By the day of the presentation, he had rehearsed the poem dozens of times and could recall it with ease. But this time, as he stood before his classmates, something strange happened. Each time he delivered the poem’s famous haunting refrain—“Quoth the Raven ‘Nevermore’ ”—the right side of his mouth quivered. The tremor intensified until, about halfway through the recitation, he fell to the floor in convulsions, having lost all control of his body, including bladder and bowels, in front of an audience of merciless adolescents. His first seizure.

My father, a neurologist, once had a patient who was tormented, in the most visceral sense, by a poem. Philip was 12 years old and a student at a prestigious boarding school in Princeton, New Jersey. One of his assignments was to recite Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. By the day of the presentation, he had rehearsed the poem dozens of times and could recall it with ease. But this time, as he stood before his classmates, something strange happened. Each time he delivered the poem’s famous haunting refrain—“Quoth the Raven ‘Nevermore’ ”—the right side of his mouth quivered. The tremor intensified until, about halfway through the recitation, he fell to the floor in convulsions, having lost all control of his body, including bladder and bowels, in front of an audience of merciless adolescents. His first seizure. I have said it before, probably irritatingly, and I will say it again several more times: one of the most remarkable literary projects of this century is being undertaken right now, as we speak, by the social historian David Kynaston. Since 2007 he has been publishing a series of books about Britain between the years 1945 and 1979, when Margaret Thatcher came to power. There have been three so far: Austerity Britain: 1945–51, Family Britain: 1951–57, and Modernity Britain: 1957–1962—roughly 2,300 pages, or 135 pages per year. If you are going to treat a country as a person, full of personality, development, joy, tragedy, regression, and contradictions—and that is what Kynaston does—then an allocation of 135 per year is actually pretty disciplined. (If, in the year 2070, someone embarks on a similar project, then the year 2020 will demand several hundred thousand words of its own.) These wonderful books deal with politics and town planning, sport and literature, music and movies, cities and the countryside, and a rather gripping narrative somehow emerges, in the same way that improvising jazz soloists find melodies.

I have said it before, probably irritatingly, and I will say it again several more times: one of the most remarkable literary projects of this century is being undertaken right now, as we speak, by the social historian David Kynaston. Since 2007 he has been publishing a series of books about Britain between the years 1945 and 1979, when Margaret Thatcher came to power. There have been three so far: Austerity Britain: 1945–51, Family Britain: 1951–57, and Modernity Britain: 1957–1962—roughly 2,300 pages, or 135 pages per year. If you are going to treat a country as a person, full of personality, development, joy, tragedy, regression, and contradictions—and that is what Kynaston does—then an allocation of 135 per year is actually pretty disciplined. (If, in the year 2070, someone embarks on a similar project, then the year 2020 will demand several hundred thousand words of its own.) These wonderful books deal with politics and town planning, sport and literature, music and movies, cities and the countryside, and a rather gripping narrative somehow emerges, in the same way that improvising jazz soloists find melodies. James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, rich, strange, and Scottish, died at eighty-four in 1799. He was known for exposing himself: he exercised naked before the open windows of his estate and eschewed travel by carriage, insisting instead on riding his horse Alburac through the damp gray of every Scottish season. Like many other men of his ilk and era—

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, rich, strange, and Scottish, died at eighty-four in 1799. He was known for exposing himself: he exercised naked before the open windows of his estate and eschewed travel by carriage, insisting instead on riding his horse Alburac through the damp gray of every Scottish season. Like many other men of his ilk and era— If the last 18 months haven’t got you thinking, then thinking probably isn’t your thing. We have witnessed microbes’ revenge on civilisation, seen the limits of the “politically possible” being reset and come to revere vaccinologists. We have learned how an economy can keep going after “business as usual” stops, and endured an enforced pause in which we could reconsider life’s priorities. Some of us were conscripted into teaching our children. Some may even have got round to reading the books they had always meant to. Many others didn’t, and got lost instead in armchair epidemiology.

If the last 18 months haven’t got you thinking, then thinking probably isn’t your thing. We have witnessed microbes’ revenge on civilisation, seen the limits of the “politically possible” being reset and come to revere vaccinologists. We have learned how an economy can keep going after “business as usual” stops, and endured an enforced pause in which we could reconsider life’s priorities. Some of us were conscripted into teaching our children. Some may even have got round to reading the books they had always meant to. Many others didn’t, and got lost instead in armchair epidemiology. It’s not easy, figuring out the fundamental laws of physics. It’s even harder when your chosen methodology is to essentially start from scratch, positing a simple underlying system and a simple set of rules for it, and hope that everything we know about the world somehow pops out. That’s the project being undertaken by Stephen Wolfram and his collaborators, who are working with a kind of discrete system called “hypergraphs.” We talk about what the basic ideas are, why one would choose this particular angle of attack on fundamental physics, and how ideas like quantum mechanics and general relativity might emerge from this simple framework.

It’s not easy, figuring out the fundamental laws of physics. It’s even harder when your chosen methodology is to essentially start from scratch, positing a simple underlying system and a simple set of rules for it, and hope that everything we know about the world somehow pops out. That’s the project being undertaken by Stephen Wolfram and his collaborators, who are working with a kind of discrete system called “hypergraphs.” We talk about what the basic ideas are, why one would choose this particular angle of attack on fundamental physics, and how ideas like quantum mechanics and general relativity might emerge from this simple framework. Just as the pandemic was gathering pace in early 2020, French President

Just as the pandemic was gathering pace in early 2020, French President  The summer that I did my chaplaincy internship was a wildly full twelve weeks. I was thirty-two years old and living in the haze of the end of an engagement as I walked the hospital corridors carrying around my Bible and visiting patients. “Hi, I’m Vanessa. I’m from the spiritual care department. How are you today?” It was a surreal summer full of new experiences hitting like a tsunami: you saw them coming but that didn’t mean you could outrun them. But the thing that never felt weird was that the Bible I carried around with me as I went to visit patient after patient, that I turned to in the guest room at David and Suzanne’s or on my parents’ couch to sustain me, was a nineteenth-century gothic Romance novel. The Bible I carried around that busy summer was Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

The summer that I did my chaplaincy internship was a wildly full twelve weeks. I was thirty-two years old and living in the haze of the end of an engagement as I walked the hospital corridors carrying around my Bible and visiting patients. “Hi, I’m Vanessa. I’m from the spiritual care department. How are you today?” It was a surreal summer full of new experiences hitting like a tsunami: you saw them coming but that didn’t mean you could outrun them. But the thing that never felt weird was that the Bible I carried around with me as I went to visit patient after patient, that I turned to in the guest room at David and Suzanne’s or on my parents’ couch to sustain me, was a nineteenth-century gothic Romance novel. The Bible I carried around that busy summer was Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. A University of Alberta-led research study followed more than 400 infants from the CHILD Cohort Study (CHILD) at its Edmonton site. Boys at one year of age with a gut bacterial composition that was high in the bacteria Bacteroidetes were found to have more advanced cognition and language skills one year later. The finding was specific to male children. “It’s well known that female children score higher (at early ages), especially in cognition and language,” said Anita Kozyrskyj, a professor of pediatrics at the U of A and principal investigator of the SyMBIOTA (Synergy in Microbiota) laboratory. “But when it comes to gut microbial composition, it was the

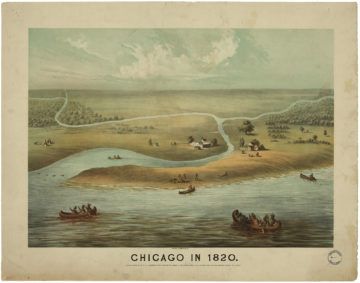

A University of Alberta-led research study followed more than 400 infants from the CHILD Cohort Study (CHILD) at its Edmonton site. Boys at one year of age with a gut bacterial composition that was high in the bacteria Bacteroidetes were found to have more advanced cognition and language skills one year later. The finding was specific to male children. “It’s well known that female children score higher (at early ages), especially in cognition and language,” said Anita Kozyrskyj, a professor of pediatrics at the U of A and principal investigator of the SyMBIOTA (Synergy in Microbiota) laboratory. “But when it comes to gut microbial composition, it was the  So, Chicago’s leaders got creative. Instead of putting sewers under the streets, they put sewers on top of the streets, then built new roads atop the old ones. They effectively hoisted the city out of the swamp.

So, Chicago’s leaders got creative. Instead of putting sewers under the streets, they put sewers on top of the streets, then built new roads atop the old ones. They effectively hoisted the city out of the swamp. We all know the story by now. The “culture wars” used to only be fought in America. In Britain, party support was strongly linked to views on an economic left-right axis; if you believed in extensive government intervention and redistribution then you voted Labour, if you believed in a small state and leaving markets to their own devices, you voted Conservative. But in the last decade, beliefs around values and identity have become increasingly important in UK as well as American politics—at the last UK general election, a voter’s position on values (for example whether they thought the death penalty should be reintroduced) was just as likely to determine their vote as their position on economics.

We all know the story by now. The “culture wars” used to only be fought in America. In Britain, party support was strongly linked to views on an economic left-right axis; if you believed in extensive government intervention and redistribution then you voted Labour, if you believed in a small state and leaving markets to their own devices, you voted Conservative. But in the last decade, beliefs around values and identity have become increasingly important in UK as well as American politics—at the last UK general election, a voter’s position on values (for example whether they thought the death penalty should be reintroduced) was just as likely to determine their vote as their position on economics.