Simon Torracinta in Boston Review:

Simon Torracinta in Boston Review:

This spring the United States embarked on a grand experiment. The American Rescue Plan, signed into law on March 11, appropriated $1.9 trillion in public spending—on top of $2.2 trillion for the CARES Act a year prior—to accelerate recovery from the dramatic economic shock of the pandemic. Combined, these measures amount to a fiscal stimulus of unprecedented scale.

Economists in the Biden administration and the Federal Reserve are bullish that this intervention will enable a rapid return to the boom times—or at least what passed for them—that preceded March 2020. They believe that running the economy “hot,” without much slack in unemployment, will extend the fruits of recovery to historically marginalized populations in the labor market and stimulate greater productive investment. Meanwhile, prominent skeptics like Larry Summers, himself a former Treasury secretary, have sounded the alarm about what they see as the significant risks and early signs of inflation, as existing capacity strains to meet the torrent of renewed demand. Implicitly, these admonitions conjure up the specter of the wage-price spirals of the 1970s.

Given the economic landscape since 2008—ultra-low interest rates, reduced worker power, low labor force participation rates—the prospects of this scenario seem rather dim. But the truth is that we don’t really know what will happen. The scale of the experiment and the sheer number of moving parts conspire to make forecasters even more uncertain than usual. Every new piece of economic data is scrutinized for augurs of the future, and entire news cycles turn on the finer points of microchip and lumber supply chains or used car sales.

Although uncertainty presents a persistent headache for central bankers and investors, it has a longstanding place in economic theory.

More here.

Stewart travels through the north of England, across moors and meadows, up mountains and through cities and villages and along coastal paths. He also voyages into the inner lives of the Brontës, showing how external place shaped their internal landscapes, how the wild fuelled their imagination.

Stewart travels through the north of England, across moors and meadows, up mountains and through cities and villages and along coastal paths. He also voyages into the inner lives of the Brontës, showing how external place shaped their internal landscapes, how the wild fuelled their imagination. He published a few books that went mostly unnoticed, but there were rumors of a trunk in his room stuffed with his true life’s work. After his death in 1935, the trunk was discovered, brimming with notes and jottings on calling cards and envelopes, whatever paper appeared to be handy. They were authored not only by Pessoa but by a flock of his personas (“heteronyms,” he called them): a doctor, a classicist, a bisexual poet, a monk, a lovesick teenage girl. Among his writings was a sheaf of papers that would become his masterpiece: “The Book of Disquiet,” a mock confession in sly, despairing aphorisms and false starts — “The active life has always struck me as the least comfortable of suicides.” In total, Pessoa created dozens of heteronyms, most complete with biographies, bodies of work, reviews and correspondence. He was awed, and a little afraid of his mind, its “overabundance.” What relation did it bear to a family history of nervous instability?

He published a few books that went mostly unnoticed, but there were rumors of a trunk in his room stuffed with his true life’s work. After his death in 1935, the trunk was discovered, brimming with notes and jottings on calling cards and envelopes, whatever paper appeared to be handy. They were authored not only by Pessoa but by a flock of his personas (“heteronyms,” he called them): a doctor, a classicist, a bisexual poet, a monk, a lovesick teenage girl. Among his writings was a sheaf of papers that would become his masterpiece: “The Book of Disquiet,” a mock confession in sly, despairing aphorisms and false starts — “The active life has always struck me as the least comfortable of suicides.” In total, Pessoa created dozens of heteronyms, most complete with biographies, bodies of work, reviews and correspondence. He was awed, and a little afraid of his mind, its “overabundance.” What relation did it bear to a family history of nervous instability? It made headlines recently when the

It made headlines recently when the  The short life of Simone Weil, the French philosopher, Christian mystic and political activist, was one of unrelenting self-sacrifice from her childhood to her death. At a very young age, she expressed an aversion to luxury. In an action that prefigured her death, while still a child, she refused to move until she was given a heavier burden to carry than her brother’s. Her death in Ashford in England in 1943, at just 34, is attributed to her apparent refusal to eat – an act of self-denial, in solidarity with starving citizens of occupied France, which she carried out despite suffering from tuberculosis. For her uncompromising ethical commitments, Albert Camus described her as ‘the only great spirit of our time’.

The short life of Simone Weil, the French philosopher, Christian mystic and political activist, was one of unrelenting self-sacrifice from her childhood to her death. At a very young age, she expressed an aversion to luxury. In an action that prefigured her death, while still a child, she refused to move until she was given a heavier burden to carry than her brother’s. Her death in Ashford in England in 1943, at just 34, is attributed to her apparent refusal to eat – an act of self-denial, in solidarity with starving citizens of occupied France, which she carried out despite suffering from tuberculosis. For her uncompromising ethical commitments, Albert Camus described her as ‘the only great spirit of our time’. You shall know them by their aspirations. Or so one might think, judging by the manifold ways in which Americans brand themselves by the things they seek to acquire and the ideals they seek to live by. Americans of all classes and identities aspire to various things, of course. The pursuit of happiness remains a central element of their national creed. But the meritocratic class has become the aspirational class par excellence. Aspiration connotes movement upward, and the meritocrat lives proudly and ostentatiously (some might even say overbearingly) in tireless pursuit of better. Little wonder that meritocrats come to think that what they and their offspring aspire to is manifestly and even morally superior to what others strive after.

You shall know them by their aspirations. Or so one might think, judging by the manifold ways in which Americans brand themselves by the things they seek to acquire and the ideals they seek to live by. Americans of all classes and identities aspire to various things, of course. The pursuit of happiness remains a central element of their national creed. But the meritocratic class has become the aspirational class par excellence. Aspiration connotes movement upward, and the meritocrat lives proudly and ostentatiously (some might even say overbearingly) in tireless pursuit of better. Little wonder that meritocrats come to think that what they and their offspring aspire to is manifestly and even morally superior to what others strive after. Now that Prometheus has basically granted every lowly lab tech superhuman powers, it’s like drinking from a data firehose if you love ancient DNA. And the more we know, the clearer it looks that genetically, all the humans on our planet group into basically three genetic types. You could think of them as 1. the very-diverse, 2. the not-very-diverse 3. the very-not-diverse (and if we’re being thorough: 4. a recent hybrid of 2 and 3.)

Now that Prometheus has basically granted every lowly lab tech superhuman powers, it’s like drinking from a data firehose if you love ancient DNA. And the more we know, the clearer it looks that genetically, all the humans on our planet group into basically three genetic types. You could think of them as 1. the very-diverse, 2. the not-very-diverse 3. the very-not-diverse (and if we’re being thorough: 4. a recent hybrid of 2 and 3.) As a refugee from the war-stricken Old World, where ethnic homogeneity had remained the defining principle of every citizenry, Arendt saw in the American republic the promise of a body politic, which absorbed newcomers without forcing them to adapt to a pre-determined homogeneity—even though she became increasingly critical of the cultural conformity of American “mass society.”

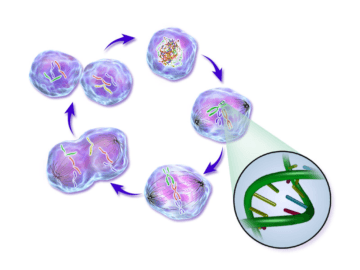

As a refugee from the war-stricken Old World, where ethnic homogeneity had remained the defining principle of every citizenry, Arendt saw in the American republic the promise of a body politic, which absorbed newcomers without forcing them to adapt to a pre-determined homogeneity—even though she became increasingly critical of the cultural conformity of American “mass society.” At the heart of all cancers is a fundamental problem: a cell—and eventually innumerable cells—that won’t stop dividing. This runaway growth is what forms a tumor, and the abnormal cellular processes that drive this growth can help tumors withstand the cancer treatments intended to kill them. Despite more than six decades of research into the mechanisms that cells use to divide, some of the nuts and bolts of the process remain a mystery. Scientists want to better understand these mechanisms in hopes of targeting them and potentially shutting down the uncontrolled growth of some tumors. New research from three collaborating teams of scientists in the United States and Europe appears to have found one of these mechanisms, uncovering a previously unknown check on dividing cells: a protein called AMBRA1. By limiting tumor growth, the researchers showed, AMBRA1 serves as an important

At the heart of all cancers is a fundamental problem: a cell—and eventually innumerable cells—that won’t stop dividing. This runaway growth is what forms a tumor, and the abnormal cellular processes that drive this growth can help tumors withstand the cancer treatments intended to kill them. Despite more than six decades of research into the mechanisms that cells use to divide, some of the nuts and bolts of the process remain a mystery. Scientists want to better understand these mechanisms in hopes of targeting them and potentially shutting down the uncontrolled growth of some tumors. New research from three collaborating teams of scientists in the United States and Europe appears to have found one of these mechanisms, uncovering a previously unknown check on dividing cells: a protein called AMBRA1. By limiting tumor growth, the researchers showed, AMBRA1 serves as an important  For better or worse, genetic testing of embryos offers a potential gateway into a new era of human control over reproduction. Couples at risk of having a child with a severe or life-limiting disease such as cystic fibrosis or Duchenne muscular dystrophy have used preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) for decades to select among embryos created through in vitro fertilization (IVF) for those that do not carry the disease-causing gene. But what new iteration of genetic testing could tempt healthy, fertile couples to reject our traditional time-tested and wildly popular process of baby making in favor of hormone shots, egg extractions and DNA analysis?

For better or worse, genetic testing of embryos offers a potential gateway into a new era of human control over reproduction. Couples at risk of having a child with a severe or life-limiting disease such as cystic fibrosis or Duchenne muscular dystrophy have used preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) for decades to select among embryos created through in vitro fertilization (IVF) for those that do not carry the disease-causing gene. But what new iteration of genetic testing could tempt healthy, fertile couples to reject our traditional time-tested and wildly popular process of baby making in favor of hormone shots, egg extractions and DNA analysis? The systems featured in Morris’s designs often suggest conflict and attrition at the micro level along with harmony at the grander scale. Within the system of the design, principles of growth relate to his conception of the forces of nature and history. He constructed his designs to mirror and even exceed the powerful generative abilities of nature; he also intended them to be vectors for the energies of history.

The systems featured in Morris’s designs often suggest conflict and attrition at the micro level along with harmony at the grander scale. Within the system of the design, principles of growth relate to his conception of the forces of nature and history. He constructed his designs to mirror and even exceed the powerful generative abilities of nature; he also intended them to be vectors for the energies of history. I kept looking at the recently infamous—now half-forgotten—picture of the Bidens visiting the Carters. The photo was taken and passed around feverishly almost two months ago, when I saw it repeatedly on my scroll and dragged the file onto my desktop, and I haven’t been able to forget it since. Everyone else moved on to Joyce Carol Oates negging Mad Men, Elon Musk going on SNL, Bennifer 2.0, and a bunch of other things I’m forgetting, but here I am, late at night, still staring at little Rosalynn, little Jimmy, big Jill, and big Joe. Also the armchairs, the blue-green walls, the blue-blue carpeting, the “unfinished” cameo-style paintings of the Carters, the blank canvas keyed to the off-white upholstery of their chairs. I’ve reviewed the institutional sheen on those cabinets, zoomed in on the trio of mask-like ceramics facing up to the ceiling on the side table, pondered the bulbous bronze bookends holding a three-volume set of something important on that same table. But mostly I’ve been staring at the little Carters and the big Bidens, trying to understand what is so transfixing to me there. And I think I finally have an answer. So at the risk of disrespecting the immutable orientation of our media universe, I want to return to the topic that was on everyone’s minds on May 3, 2021. I want to turn and watch the sunset.

I kept looking at the recently infamous—now half-forgotten—picture of the Bidens visiting the Carters. The photo was taken and passed around feverishly almost two months ago, when I saw it repeatedly on my scroll and dragged the file onto my desktop, and I haven’t been able to forget it since. Everyone else moved on to Joyce Carol Oates negging Mad Men, Elon Musk going on SNL, Bennifer 2.0, and a bunch of other things I’m forgetting, but here I am, late at night, still staring at little Rosalynn, little Jimmy, big Jill, and big Joe. Also the armchairs, the blue-green walls, the blue-blue carpeting, the “unfinished” cameo-style paintings of the Carters, the blank canvas keyed to the off-white upholstery of their chairs. I’ve reviewed the institutional sheen on those cabinets, zoomed in on the trio of mask-like ceramics facing up to the ceiling on the side table, pondered the bulbous bronze bookends holding a three-volume set of something important on that same table. But mostly I’ve been staring at the little Carters and the big Bidens, trying to understand what is so transfixing to me there. And I think I finally have an answer. So at the risk of disrespecting the immutable orientation of our media universe, I want to return to the topic that was on everyone’s minds on May 3, 2021. I want to turn and watch the sunset.