Benjamin Wallace-Wells in The New Yorker:

Television suits Peter Buttigieg. He is a dispassionate figure in an emotional medium. In response to ridiculousness, his face stays largely still, but his peaked eyebrows rise a notch. As a politician, Buttigieg’s great trick (it’s also a flaw) is to never take anything personally: he blinks away the noisy, slanderous business of daily politics in pursuit of what political consultants might call the point of essential contrast.

Television suits Peter Buttigieg. He is a dispassionate figure in an emotional medium. In response to ridiculousness, his face stays largely still, but his peaked eyebrows rise a notch. As a politician, Buttigieg’s great trick (it’s also a flaw) is to never take anything personally: he blinks away the noisy, slanderous business of daily politics in pursuit of what political consultants might call the point of essential contrast.

Lately, Buttigieg has been not taking things personally on Fox News. Liberals, even those who had grown tired of his dogged reasonableness, have celebrated each of his three recent appearances on the network as a tour de force and a rout. Just before the Vice-Presidential debate, last Wednesday, Buttigieg was asked on Fox News about the policy differences between Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. He replied, “Well, there’s a classic parlor game of trying to find a little bit of daylight between running mates, and if people want to play that game we could look into why an evangelical Christian like Mike Pence wants to be on a ticket with a President caught with a porn star.” Pence, President, porn—he captured the basic deal Republicans had made with power in three tight plosives. (Slayer Pete, Mary McNamara of the Los Angeles Times named this persona, brilliantly.)

It’s tempting to conclude that Buttigieg’s recent star turns on Fox News say less about him than they do about the network, whose hosts spend so much time ridiculing liberal positions that they can find themselves at a loss when those positions are presented in earnest. Last week, the “Fox and Friends” host Steve Doocy asked Buttigieg about President Trump’s choice not to participate in a virtual debate with Biden. “All of us have had to get used to virtual formats,” Buttigieg said, pointing out that parents trying to manage home learning had it much rougher than the President of the United States. He went on, “The only reason that we’re here in the first place is that the President of the United States is still contagious, as far as we know, with a deadly disease.” That clip, like his response to the question about Harris, went viral, partly because Doocy kept encouraging Buttigieg, as he usually does ideologically friendlier guests, with a series of confident-sounding local-news-anchor noises: “Sure . . . Right . . . Yeah . . . Sure . . . Right . . . Right . . . Sure.”

Fox News has always been a good venue for Buttigieg, for reasons that don’t have much to do with the dimness of its morning hosts. Last spring, a Fox audience stood at the end of a town hall with Buttigieg. “Wow! A standing ovation!” the Fox News anchor Chris Wallace said, apparently surprised by it. The network’s orientation, on both the hyperbolic evening shows and the Doocified morning ones, borrows the spirit, if not the prudity, of religious conservatives: the heartland is virtuous, and the liberal city sinful. Beamed in from Indiana, Buttigieg has a way of inverting all of that.

More here.

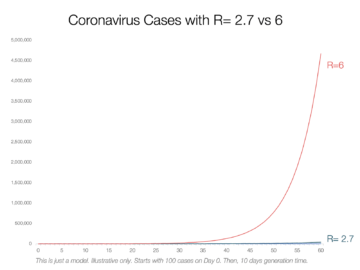

The original Coronavirus variant has an R0 of ~2.71. Alpha—the “English variant” that caused a spike around the world around Christmas—is about 60% more infectious. Now it appears that Delta is about 60% more transmissible yet again. Depending on which figureyou use, it would put Delta’s R0 between 4 and 9, which could make it more contagious than smallpox. Just to give you a sense of the dramatic consequence of such an increase in R, this is what two months of growth get you with the previous transmission rate of 2.7 vs. with an R of 6 [see figure].

The original Coronavirus variant has an R0 of ~2.71. Alpha—the “English variant” that caused a spike around the world around Christmas—is about 60% more infectious. Now it appears that Delta is about 60% more transmissible yet again. Depending on which figureyou use, it would put Delta’s R0 between 4 and 9, which could make it more contagious than smallpox. Just to give you a sense of the dramatic consequence of such an increase in R, this is what two months of growth get you with the previous transmission rate of 2.7 vs. with an R of 6 [see figure].

Identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are the beginning and the end of the self. They are how we define ourselves and how we are defined by others. One is a “nerd” or a “jock” or a “know-it-all.” One is “liberal” or “conservative,” “religious” or “secular,” “white” or “black.” Identities are the means of escape and the ties that bind. They direct our thoughts. They are modes of being. They are an ingredient of the self—along with relationships, memories, and role models—and they can also destroy the self. Consume it. The Jungians are right when they say people don’t have identities, identities have people. And the Lacanians are righter still when they say that our very selves—our wishes, desires, thoughts—are constituted by other people’s wishes, desires, and thoughts. Yes, identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are expressions of inner selves, and a way the outside gets in.

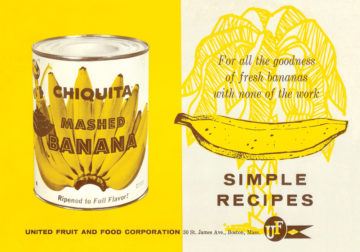

Identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are the beginning and the end of the self. They are how we define ourselves and how we are defined by others. One is a “nerd” or a “jock” or a “know-it-all.” One is “liberal” or “conservative,” “religious” or “secular,” “white” or “black.” Identities are the means of escape and the ties that bind. They direct our thoughts. They are modes of being. They are an ingredient of the self—along with relationships, memories, and role models—and they can also destroy the self. Consume it. The Jungians are right when they say people don’t have identities, identities have people. And the Lacanians are righter still when they say that our very selves—our wishes, desires, thoughts—are constituted by other people’s wishes, desires, and thoughts. Yes, identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are expressions of inner selves, and a way the outside gets in. The United Fruit Company was born over a bottle of rum. In 1870, Lorenzo Dow Baker, skipper of the Boston schooner Telegraph, pulled into Jamaica for a taste of the island’s famous distilled alcohol and a load of bamboo. While he was drinking, a local tradesman came by offering green bananas; Baker bought 160 bunches at twenty-five cents each. He resold them in New York for up to $3.25 a bunch, a deal so sweet he couldn’t resist doing it again. By 1885, eleven ships were flying under the banner of the new Boston Fruit Company, bringing to the United States ten million bunches of bananas a year. United Fruit was formed in 1899, with assets that included more than 210,000 acres of land across the Caribbean and Central America and enough political clout that Honduras, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region became known as “banana republics.”

The United Fruit Company was born over a bottle of rum. In 1870, Lorenzo Dow Baker, skipper of the Boston schooner Telegraph, pulled into Jamaica for a taste of the island’s famous distilled alcohol and a load of bamboo. While he was drinking, a local tradesman came by offering green bananas; Baker bought 160 bunches at twenty-five cents each. He resold them in New York for up to $3.25 a bunch, a deal so sweet he couldn’t resist doing it again. By 1885, eleven ships were flying under the banner of the new Boston Fruit Company, bringing to the United States ten million bunches of bananas a year. United Fruit was formed in 1899, with assets that included more than 210,000 acres of land across the Caribbean and Central America and enough political clout that Honduras, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region became known as “banana republics.” This year, Tate is hosting four exhibitions devoted to women artists: Paula Rego, Lubaina Himid, Yayoi Kusama and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a further show devoted to Magdalena Abakanowicz is in the pipeline). Opening on 15 July at Tate Modern, the exhibition ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction’ comes with an excellent catalogue, which includes sixteen essays that survey her remarkable range. This Swiss artist, born in Davos in 1889, created textiles, beadwork bags and necklaces, cross-stitch embroidery, carnivalesque outfits for costume balls and a family of haunting marionettes, as well as designing furniture and interiors. She was also a Laban-trained dancer, a sculptor, an illustrator, co-editor of the important journal Plastique, a brilliant photographer and a significant abstract artist. And as if that were not enough, she gave continuous support to her husband, Jean Arp, and designed the modern vernacular house at Clamart in the southwestern suburbs of Paris where she and Arp lived from 1928 until being driven south by the German invasion in 1940. Her husband, whom she married in 1922, is regularly name-checked in surveys of 20th-century art, from Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting to Norbert Lynton’s The Story of Modern Art. By contrast, Taeuber-Arp’s reputation was only properly recuperated in 2005 in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh’s generous Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism.

This year, Tate is hosting four exhibitions devoted to women artists: Paula Rego, Lubaina Himid, Yayoi Kusama and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a further show devoted to Magdalena Abakanowicz is in the pipeline). Opening on 15 July at Tate Modern, the exhibition ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction’ comes with an excellent catalogue, which includes sixteen essays that survey her remarkable range. This Swiss artist, born in Davos in 1889, created textiles, beadwork bags and necklaces, cross-stitch embroidery, carnivalesque outfits for costume balls and a family of haunting marionettes, as well as designing furniture and interiors. She was also a Laban-trained dancer, a sculptor, an illustrator, co-editor of the important journal Plastique, a brilliant photographer and a significant abstract artist. And as if that were not enough, she gave continuous support to her husband, Jean Arp, and designed the modern vernacular house at Clamart in the southwestern suburbs of Paris where she and Arp lived from 1928 until being driven south by the German invasion in 1940. Her husband, whom she married in 1922, is regularly name-checked in surveys of 20th-century art, from Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting to Norbert Lynton’s The Story of Modern Art. By contrast, Taeuber-Arp’s reputation was only properly recuperated in 2005 in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh’s generous Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism. Television suits

Television suits  US President Joe Biden’s administration wants to create a US$6.5-billion agency to accelerate innovations in health and medicine — and revealed new details about the unit last month

US President Joe Biden’s administration wants to create a US$6.5-billion agency to accelerate innovations in health and medicine — and revealed new details about the unit last month In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”,

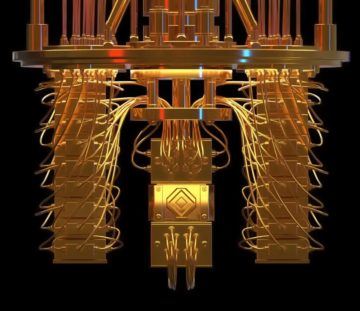

In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”, Quantum computers

Quantum computers As a new parent of boy/girl twins (at least as they were assigned at birth), I puzzle about the cultural pressure to scrutinise my infant son’s burgeoning masculinity lest it emerge as ‘toxic’. I catch myself watching and wondering, resisting the urge to police his interactions with his sister: He took the toy she was playing with, is this aggression that will stifle her confidence? She seems unbothered and has quickly snatched it back – phew! Is it bullying or an early form of manspreading when, both of them vying for the same object, he moves into her space and pushes her aside?

As a new parent of boy/girl twins (at least as they were assigned at birth), I puzzle about the cultural pressure to scrutinise my infant son’s burgeoning masculinity lest it emerge as ‘toxic’. I catch myself watching and wondering, resisting the urge to police his interactions with his sister: He took the toy she was playing with, is this aggression that will stifle her confidence? She seems unbothered and has quickly snatched it back – phew! Is it bullying or an early form of manspreading when, both of them vying for the same object, he moves into her space and pushes her aside? The saltwater aquarium in my new dentist’s office is its best feature. My favorite fish is a red fish with big eyes and a black stripe along its back. He has a generally grumpy demeanor, and I cannot help but feel a friendship form between us. I take photos of him and sometimes post them to Instagram. (“This red fish is my favorite fish, he is a total weirdo.”) He is popular among my friends.

The saltwater aquarium in my new dentist’s office is its best feature. My favorite fish is a red fish with big eyes and a black stripe along its back. He has a generally grumpy demeanor, and I cannot help but feel a friendship form between us. I take photos of him and sometimes post them to Instagram. (“This red fish is my favorite fish, he is a total weirdo.”) He is popular among my friends. Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. But even when Newton was performing his intellectual feats at Cambridge in the 1680s, he was eager to move on to a new life. Patricia Fara, historian of science at Cambridge University, seeks to chronicle that period in “Life after Gravity: Isaac Newton’s London Career.” In this book she presents Newton as “a metropolitan performer, a global actor who played various parts.”

Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. But even when Newton was performing his intellectual feats at Cambridge in the 1680s, he was eager to move on to a new life. Patricia Fara, historian of science at Cambridge University, seeks to chronicle that period in “Life after Gravity: Isaac Newton’s London Career.” In this book she presents Newton as “a metropolitan performer, a global actor who played various parts.” Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website:

Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website: