Category: Recommended Reading

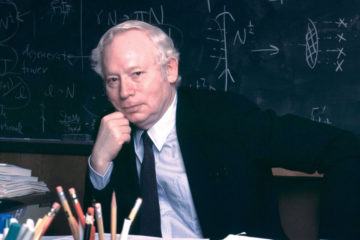

Death of World-Renowned Physicist Steven Weinberg

From UT News:

In 1967, Weinberg published a seminal paper laying out how two of the universe’s four fundamental forces — electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force — relate as part of a unified electroweak force. “A Model of Leptons,” at barely three pages, predicted properties of elementary particles that at that time had never before been observed (the W, Z and Higgs boson) and theorized that “neutral weak currents” dictated how elementary particles interact with one another. Later experiments, including the 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland, would bear out each of his predictions.

Weinberg leveraged his renown and his science for causes he cared deeply about. He had a lifelong interest in curbing nuclear proliferation and served briefly as a consultant for the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency.

Saturday, July 24, 2021

Why Neoliberalism Needs Neofascists

Prabhat Patnaik in Boston Review:

Prabhat Patnaik in Boston Review:

It has been four decades since neoliberal globalization began to reshape the world order. During this time, its agenda has decimated labor rights, imposed rigid limits on fiscal deficits, given massive tax breaks and bailouts to big capital, sacrificed local production for multinational supply chains, and privatized public sector assets at throwaway prices.

The result today is a perverse regime defined by the free movement of capital, which moves relatively effortlessly across international borders, even as free movement of the people is ruthlessly controlled by a sharp increase in income inequality and a steady winnowing of democracy. No matter who comes to power, no matter what promises are made before elections, the same economic policies are followed. Since capital, especially finance, can leave a country en masse at extremely short notice—precipitating an acute financial crisis if its “confidence” in a country is undermined—governments are loath to upset the status quo; they pursue policies favorable to finance capital and indeed demanded by it. The sovereignty of the people, in short, is replaced by the sovereignty of global finance and the domestic corporations integrated with it.

This abridgment of democracy is usually justified by political and economic elites on the grounds that neoliberal economic policies usher in higher GDP growth—considered the summum bonum after which all policy should aim. And indeed, in many countries, especially in Asia, the neoliberal era has ushered in noticeably more rapid growth than under the earlier period of dirigisme. Such growth scarcely benefits the bulk of the people, of course: in fact, neoliberal policies are even more highly associated with the growth of income inequality than with the growth of GDP. (Even International Monetary Fund economists Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri concede this point in their 2016 article “Neoliberalism: Oversold?”) But neoliberals have sold a powerful response to this objection: a rise in income inequality should be considered an acceptable price to pay for more rapid growth, for it still might mean an absolute improvement in the conditions of the worst off. The fundamental ideological conceit of neoliberalism has been that growth will lift all boats, even if some boats rise much more than others.

More here.

Path Persistence

Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

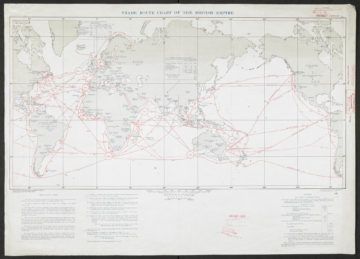

During the first era of globalization (1870–1913), the global division of labor was stark. Britain and other Western nations largely produced manufactured goods, but they also exported a whole range of temperate agricultural goods like wheat, beef and barley. Elsewhere in the European colonial empires, products like cotton, cocoa and coffee were exported, often at very low prices and sometimes with forced labor, to sate a growing demand in the global economic core for tropical luxuries. More than a century has passed since World War I heralded the collapse of this world order. Today, the globalization wave that has shaped the world since the 1980s is ebbing.

What is the legacy of the First Globalization of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries on the economic fortunes of countries during the Second Globalization? To what extent have countries’ positions in the international economic order been persistent across the two globalizations, with some trapped at the bottom and others comfortably on top?

Long-term development trajectories are commonly explained through the convergence hypothesis. Derived from neoclassical growth theory, it states that “initial conditions have no implications for the long-run distribution of per capita income.” The hypothesis suggests that history has no persistent bearing on countries’ relative wealth: if left to the laws of the market, poorer countries are expected to catch up by outperforming richer countries in their rates of economic growth. However, the convergence hypothesis is not backed by empirical evidence—extensive testing has not heralded the results that standard growth theory would expect. In an effort to elucidate these findings, a quickly growing “persistence literature” has proposed a range of explanations for why countries’ relative wealth today is historically rooted in institutional quality (referring in this case to property rights regimes and liberal representative democracy), culture, religion, geography, or even genetics.

More here.

‘Roadrunner’ and the Dismal Search for the ‘Real Bourdain’

Maria Bustillos in Eater:

Maria Bustillos in Eater:

An obscure, 43-year-old chef and author of minor crime novels is reborn, after a sudden and unexpected literary success, into a life of global fame and influence. A charmed life, cut short when he hanged himself in a hotel bathroom in Alsace 18 years later. This is the story of Roadrunner, the new documentary about the late Anthony Bourdain directed by Morgan Neville.

The film is an elegant montage of interviews with Bourdain’s intimates — chefs David Chang and Eric Ripert, painter David Choe, musicians Josh Homme and John Lurie, Ottavia Busia (his second wife, and the mother of his daughter Ariane), and many others — intercut with images of rock stars, writers, and classic films he admired, and archival footage from a long, strange career in front of the camera. Over the years the boyishly awkward, Rundgrenesquely toothy grin of 1999 gives way to Bourdain’s familiarly friendly, knowing, jaded smile.

Since Bourdain’s death, the desire to get to the Real Truth of Bourdain has been as fervent as his memorialization. In the brave new world of social media influencers and reality TV, an awareness of the artificiality of even the most “authentic” branded personality is taken for granted; maybe more than that, people want — and even need — to know how someone so loved and admired could have slipped beyond the reach of friends, of help. And so the intense drive to understand the space between the genuine Bourdain and the Bourdain on camera grew. What Neville has attempted to do with Roadrunner is to close that gap.

More here.

Julie Mehretu and Shahzia Sikander In Conversation

The Radical Women Who Paved the Way for Free Speech and Free Love

Margaret Talbot in The New Yorker:

Anthony Comstock may be the only man in American history whose lobbying efforts yielded not only the exact federal law he wanted but the privilege of enforcing it to his liking for four decades. Given that Comstock never held elected office and that the highest appointed position he occupied in government was special agent of the Post Office, this was an extraordinary achievement—and a reminder of the ways that zealots have sometimes slipped past the sentries of American democracy to create a reality that the rest of us must live in. Comstock was an anti-vice crusader who worried about many of the things that Americans of a similar moral and religious cast worried about in the late nineteenth century: the rise of the so-called sporting press, which specialized in randy gossip and user guides to local brothels; the phenomenon of young men and women set loose in big cities, living, unsupervised, in cheap rooming houses; the enervating effects of masturbation; the ravages of venereal disease; the easy availability of contraceptives, such as condoms and pessaries, and of abortifacients, dispensed by druggists or administered by midwives. But Comstock railed against all these things more passionately than most of his contemporaries did, and far more effectively.

Anthony Comstock may be the only man in American history whose lobbying efforts yielded not only the exact federal law he wanted but the privilege of enforcing it to his liking for four decades. Given that Comstock never held elected office and that the highest appointed position he occupied in government was special agent of the Post Office, this was an extraordinary achievement—and a reminder of the ways that zealots have sometimes slipped past the sentries of American democracy to create a reality that the rest of us must live in. Comstock was an anti-vice crusader who worried about many of the things that Americans of a similar moral and religious cast worried about in the late nineteenth century: the rise of the so-called sporting press, which specialized in randy gossip and user guides to local brothels; the phenomenon of young men and women set loose in big cities, living, unsupervised, in cheap rooming houses; the enervating effects of masturbation; the ravages of venereal disease; the easy availability of contraceptives, such as condoms and pessaries, and of abortifacients, dispensed by druggists or administered by midwives. But Comstock railed against all these things more passionately than most of his contemporaries did, and far more effectively.

Nassau Street, at the lower tip of Manhattan, was a particular horror to him—a groaning board of Boschian temptations. As Amy Sohn details in her fascinating book “The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship & Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), when Comstock arrived in New York as a young man, just after the Civil War, he was appalled to see an open market in sex toys and contraceptive devices (both often hawked as “rubber goods”), along with smutty playing cards, books, and stereoscopic images. At the wholesale notions establishment where he held a job, Comstock lamented that the young men he worked with were “falling like autumn leaves about me from the terrible scourges of vile books and pictures.”

More here.

I don’t: my very modern marriage

Anna Baddeley in 1843 Magazine:

You can hold hands if you want to.” We had arrived at the part in our ceremony where we had to parrot a legal declaration, and the registrar was clearly desperate to inject some romance into proceedings.

You can hold hands if you want to.” We had arrived at the part in our ceremony where we had to parrot a legal declaration, and the registrar was clearly desperate to inject some romance into proceedings.

In June, my partner and I were bound together in the eyes of the British state. We didn’t get married though – we got a civil partnership, a type of union invented for gay couples in 2004 that was recently opened up to straight couples after a long campaign to change the law. We had opted for a pared-down ceremony, with no guests apart from the two friends who were acting as our witnesses. The venue was Room 99, the cheapest space to get married at Islington Town Hall in north London. “I’d rather not hold his hand,” I said. “Mine are too sweaty.” The registrar apologised, worried she had offended me. I hadn’t meant to make her feel awkward, but I’m one of those people who instinctively makes a joke when put in an uncomfortable situation. And I was keen for the ceremony to be as unromantic as possible. We were doing this not for love, but for tax.

The social and economic rationale behind marriage used to be clear: sanctified, legal reproduction; a business deal between two families. Now that the feudal backdrop has disappeared, people get married for more waffly reasons. For most millennials, it’s merely an excuse for a party. When marriage is seen purely as a celebration of love, the legal and financial benefits are obscured. I suspect few of my friends got married because of the tax breaks, but in Britain marriage can reduce your income-tax bill, capital-gains tax and the inheritance tax your children have to pay (you also get automatic status as the next of kin in times of crisis and the right to claim some of your spouse’s money if you break up).

More here.

Saturday Poem

The Park

In that oblivious, concentrated, fiercely fetal decontraction peculiar to

………. the lost,

a grimy derelict is flat out on a green bench by the sandbox, gazing

………. blankly at the children.

“Do you want to play with me?” a small boy asks another, his fine head

………. tilted deferentially.

but the other has a lovely fire truck so he doesn’t have answer and

………. emphatically doesn’t,

he just grinds his toy, its wheel immobilized with grit, along the low

………. stone wall.

The first child sinks forlornly down and lays his palms against the earth

………. like Buddha.

The ankles of the derelict are scabbed and swollen, torn with aching

………. varicose and cankers.

Who will come to us now? Who will solace us? Who will take us in

………. their healing hands?

by C.K. Williams

from Selected Poems

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994

Friday, July 23, 2021

A Total Work of Art: On Leos Carax’s Annette (2021)

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Every era gets the Gesamtkunstwerk it deserves. In Richard Wagner’s 1849 essay, The Artwork of the Future, the German composer conceives theater as the ideal site for the reintegration of dance, tone, and poetry, which had been separated out after their original unity in Greek drama. Architecture, too, was to be incorporated into the new unified mega-art, as the art of framing the total theater staged within its edifice. And there is drama too, which already on its own, Wagner thinks, is a sort of “conjoint” totality, “since it can only be at hand in all its possible fullness, when in it each separate branch of art is at hand in it in its own utmost fullness.”

Every era gets the Gesamtkunstwerk it deserves. In Richard Wagner’s 1849 essay, The Artwork of the Future, the German composer conceives theater as the ideal site for the reintegration of dance, tone, and poetry, which had been separated out after their original unity in Greek drama. Architecture, too, was to be incorporated into the new unified mega-art, as the art of framing the total theater staged within its edifice. And there is drama too, which already on its own, Wagner thinks, is a sort of “conjoint” totality, “since it can only be at hand in all its possible fullness, when in it each separate branch of art is at hand in it in its own utmost fullness.”

The four-part opera cycle Der Ring der Nibelungen (1869-1876) was his most complete attempt to realize such an all-embracing work, building layers of Germanic mythology —the Volk being the “force that conditions the artwork”— onto an earlier Romantic sensibility in the vein of Giacomo Meyerbeer that Wagner would infamously come to despise as all so much “Judenthum”. The völkisch element is not just in the libretto, the set design, and the costumes, but in the music itself, and of course there was a large budget at Bayreuth for fuming dragons and other such effects. Wagner was himself known to fume when his pyrotechnics malfunctioned.

More here.

How the Delta variant achieves its ultrafast spread

Sara Reardon in Nature:

Since first appearing in India in late 2020, the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has become the predominant strain in much of the world. Researchers might now know why Delta has been so successful: people infected with it produce far more virus than do those infected with the original version of SARS-CoV-2, making it very easy to spread.

Since first appearing in India in late 2020, the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has become the predominant strain in much of the world. Researchers might now know why Delta has been so successful: people infected with it produce far more virus than do those infected with the original version of SARS-CoV-2, making it very easy to spread.

According to current estimates, the Delta variant could be more than twice as transmissible as the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. To find out why, epidemiologist Jing Lu at the Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Guangzhou, China, and his colleagues tracked 62 people who were quarantined after exposure to COVID-19 and who were some of the first people in mainland China to become infected with the Delta strain.

The team tested study participants’ ‘viral load’ — a measure of the density of viral particles in the body — every day throughout the course of infection to see how it changed over time. Researchers then compared participants’ infection patterns with those of 63 people who contracted the original SARS-CoV-2 strain in 2020.

More here.

My 24 hours in Mexico’s 21st-century migrant prison

Belen Fernandez at Aljazeera:

As someone prone to panic attacks and spectacularly inept at dealing with adversity in life, I found it immensely comforting to have two Cuban feet in my face all night. I was also well aware that my visible fragility was less than endearing in a detention situation created in large part by my own nation – a situation from which, thanks to my passport privilege, I would inevitably be extricated with relatively minimal suffering.

As someone prone to panic attacks and spectacularly inept at dealing with adversity in life, I found it immensely comforting to have two Cuban feet in my face all night. I was also well aware that my visible fragility was less than endearing in a detention situation created in large part by my own nation – a situation from which, thanks to my passport privilege, I would inevitably be extricated with relatively minimal suffering.

While my fellow inmates could not fathom why the neurotic gringa was resisting return to the country they were risking their lives to reach, they charitably restricted their reactions to hysterical laughter at the ironic prospect of being deported to the US.

I would later learn that when my mother phoned the US embassy in Mexico, she was told that I would likely be held at Siglo XXI for at least two weeks, and that the US government could not intervene: “We cannot tell Mexico what to do.”

More here.

A Great Figure Has Passed: RIP, Manouri Muttetuwegama

Graham Greene’s God

John Banville at The Nation:

Evelyn Waugh liked to tease Graham Greene by remarking that it was a good thing God exists, because otherwise Greene would be a Laurel without Hardy. It is a mark in Greene’s favor that he recounts the jibe in a tribute to Waugh written shortly after his friend’s death in 1966. Throughout his life, the fabulously successful Greene was ever ready to pull his own leg, such as when, in 1949, he entered a New Statesman competition by submitting three parodies of his own writing under pseudonyms. One of the entries was judged good enough to merit a guinea of the six-guinea prize. Greene then wrote a letter to the editor owning up to the prank and regretting that he had not won the contest outright, especially as the money would be tax-free—always an important consideration with Greene.

Evelyn Waugh liked to tease Graham Greene by remarking that it was a good thing God exists, because otherwise Greene would be a Laurel without Hardy. It is a mark in Greene’s favor that he recounts the jibe in a tribute to Waugh written shortly after his friend’s death in 1966. Throughout his life, the fabulously successful Greene was ever ready to pull his own leg, such as when, in 1949, he entered a New Statesman competition by submitting three parodies of his own writing under pseudonyms. One of the entries was judged good enough to merit a guinea of the six-guinea prize. Greene then wrote a letter to the editor owning up to the prank and regretting that he had not won the contest outright, especially as the money would be tax-free—always an important consideration with Greene.

more here.

Argentina as a Land Expecting the Undelivered Epic

Arturo Desimone at Berfrois:

Greeks who have met Argentines, and Argentines who travel to Greece, often wax on strange parallels — on the discovery of inexplicable and unexpected similarities between peoples, like stumbling upon an enchanted mirror that mocks.

Greeks who have met Argentines, and Argentines who travel to Greece, often wax on strange parallels — on the discovery of inexplicable and unexpected similarities between peoples, like stumbling upon an enchanted mirror that mocks.

“Brothers! We are brothers” old Greek and Cypriot men in suspenders shudder, standing in their shops, their fingers interlock before hugging me as they’d embrace an image of their youth — a lost friend from their military service; the fading energy in their brains is jolted by the twilight of remembrance before Hades’ dusk enters the deep creases of their faces. “We are brothers, brothers…” Never would I rob my elders of sentimental illusions.

In some important ways, Greeks and Riverplateans (ríoplatenses) mirror each other — partly the result of the immigrant cultures that populated the La Plata river basin at the close of the 19th century (the botched healing of that salted wound of a century, whose influence continues bleeding surreptitiously into Argentinian culture today.)

more here.

Richard Linklater Presents: Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

Manifesto Destiny: Writing that demands change now

Lidija Haas in Bookforum:

MANIFESTO IS THE FORM THAT EATS AND REPEATS ITSELF. Always layered and paradoxical, it comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries—something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. While appearing to invent itself ex nihilo, the manifesto grabs whatever magpie trinkets it can find, including those that drew the eye in earlier manifestos. This is a form that asks readers to suspend their disbelief, and so like any piece of theater, it trades on its own vulnerability, invites our complicity, as if only the quality of our attention protects it from reality’s brutal puncture. A manifesto is a public declaration of intent, a laying out of the writer’s views (shared, it’s implied, by at least some vanguard “we”) on how things are and how they should be altered. Once the province of institutional authority, decrees from church or state, the manifesto later flowered as a mode of presumption and dissent. You assume the writer stands outside the halls of power (or else, occasionally, chooses to pose and speak from there). Today the US government, for example, does not issue manifestos, lest it sound both hectoring and weak. The manifesto is inherently quixotic—spoiling for a fight it’s unlikely to win, insisting on an outcome it lacks the authority to ensure.

MANIFESTO IS THE FORM THAT EATS AND REPEATS ITSELF. Always layered and paradoxical, it comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries—something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. While appearing to invent itself ex nihilo, the manifesto grabs whatever magpie trinkets it can find, including those that drew the eye in earlier manifestos. This is a form that asks readers to suspend their disbelief, and so like any piece of theater, it trades on its own vulnerability, invites our complicity, as if only the quality of our attention protects it from reality’s brutal puncture. A manifesto is a public declaration of intent, a laying out of the writer’s views (shared, it’s implied, by at least some vanguard “we”) on how things are and how they should be altered. Once the province of institutional authority, decrees from church or state, the manifesto later flowered as a mode of presumption and dissent. You assume the writer stands outside the halls of power (or else, occasionally, chooses to pose and speak from there). Today the US government, for example, does not issue manifestos, lest it sound both hectoring and weak. The manifesto is inherently quixotic—spoiling for a fight it’s unlikely to win, insisting on an outcome it lacks the authority to ensure.

Somewhere a manifesto is always being scrawled, but the ones that survive have usually proliferated at times of ferment and rebellion, like the pamphlets of the Diggers in seventeenth-century England, or the burst of exhortations that surrounded the French Revolution, including, most memorably, Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. The manifesto is a creature of the Enlightenment: its logic depends on ideals of sovereign reason, social progress, a universal subject on whom equal rights should (must) be bestowed.

More here.

Gun violence is surging — researchers finally have the money to ask why

Nidhi Subbaraman in Nature:

Maeve Wallace has studied maternal health in the United States for more than a decade, and a grim statistic haunts her. Five years ago, she published a study showing that being pregnant or recently having had a baby nearly doubles a woman’s risk of being killed1. More than half of the homicides she tracked, using data from 37 states, were perpetrated with a gun.

Maeve Wallace has studied maternal health in the United States for more than a decade, and a grim statistic haunts her. Five years ago, she published a study showing that being pregnant or recently having had a baby nearly doubles a woman’s risk of being killed1. More than half of the homicides she tracked, using data from 37 states, were perpetrated with a gun.

In March 2020, she saw something she hadn’t seen before: a funding opportunity from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study deaths and injuries from gun violence. She had mentioned firearms in her studies before. But knowing that the topic is politically fraught, she often tucked related terms and findings deep within her papers and proposals. This time, she says, she felt emboldened to focus on guns specifically, and to ask whether policies that restrict firearms for people convicted of domestic violence would reduce the death rate for new and expecting mothers. Male partners are the killers in nearly half of homicides involving women in the United States. “This call for proposals really motivated me to ask the research questions that I may not have otherwise asked,” says Wallace, an epidemiologist at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Wallace’s group is one of several dozen funded by a new pool of federal money for gun-violence research in the United States, which has more firearm-related deaths than any other wealthy nation. Although other countries fund research on guns, it is often in the context of trafficking and armed conflict. US federal funding of gun-violence research has not reflected the death toll, researchers say.

More here.

Friday Poem

Azza and I Share a Cup of Tea

and Azza pours the tea before she speaksAzza never looks the same.

Each time you get close enough, each time you think you know her,

she reveals another surfaceIf you don’t pay attention, you might almost miss it

the way her crisp white toub falls gracefully on her shoulders,

how the gold crescent in her nose accentuates her face tenderlyAzza is timid, but captures your attention

She is not a mere stop on your destination

So, plan to stay awhile.Listen to the way she uses language to weave stories full of heart

Pay attention to how she sings songs of love

Count the scars and ask her how many battles she has foughtYou will be surprised to learn how many of them she’s won.

Sip your tea slowly and know that she will offer you a place to stay

Let her soft voice trickle into your ears, and

Let the cool breeze touch your skin

No need for formalities,

Azza has no care for them

She has no need for ceremony nor procedure

She takes big leaps, wanders on the dangerous route

She fears nothing, and is ready to risk it all

She is fearless, but never reckless

Beautiful, but never boastful

Smart, and always dreaming

She paints pictures of hopes and what-ifs

See how her eyes light up when she talks of future

Notice when she smiles

Because it does not happen often

Savor the moment,

Ask her the questions

Listen to the answers

Sip your tea slowly

by Leena Badri

from Pank Magazine 1.1-2020

Thursday, July 22, 2021

At 23, Amartya Sen finished the work for his PhD in one year and then set up an economics department

An excerpt from the Nobel Laureate’s memoir, Home in the World, at Scroll.in:

By June 1956, at the end of my first year as a research student, I had a set of chapters that looked as if they could form a dissertation. A substantial number of economists at various universities were work ing then on different ways of choosing between techniques of production. Some were particularly focused on maximising the total value of the output produced, whereas others wanted to maximise the surplus that was generated, and there were also some profit maximisers.

By June 1956, at the end of my first year as a research student, I had a set of chapters that looked as if they could form a dissertation. A substantial number of economists at various universities were work ing then on different ways of choosing between techniques of production. Some were particularly focused on maximising the total value of the output produced, whereas others wanted to maximise the surplus that was generated, and there were also some profit maximisers.

Analysing these – and other – approaches, and taking note of the fact that a higher surplus, when reinvested, could lead to a higher rate of growth and through that to a higher output in the future, the different criteria could be compared through assessing alternative time series of outputs and consumption.

I was sure that the unruly literature on all this could be sorted out and nicely disciplined through comparative evaluation of alternative time series, which turned out to be fun to do. I called it the “time series approach”. I was glad to be able to outline an easily discussable general methodology for the various alternative proposals that were being offered.

More here.