https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WqNkjNf6ceI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WqNkjNf6ceI

We came down from the Chiricahua Mountains,

went even closer to the border, hiked rocky

hillsides off-road, spotted a five-striped sparrow,

so fine, yet overshadowed by the rotor noise

of the sporadic helicopter overhead. Our guide

said to hold up our binoculars, let them know

we were only birdwatchers, and we complied,

having already passed trucks stopped in the desert,

unloading ATVs that armed and armored men

rode off. Earlier, I’d asked about the tethered

gray dirigibles in the otherwise cloudless sky,

was told they were platforms for surveillance.

Overseas for decades, much of it in conflict

areas, I’d never seen such heavy arms, such war

materiel in my country, not outside military

bases. The border sun was bright, our pace

slow, but still, I had to close my eyes, breath

caught with twinges of fear and vertigo, darkness

in waves like a mirage, waves of sparrows fallen

by vertiginous plunge or slow slump, in the desert,

unseen by any person, me among them.

by Sandra Gustin

from The Poetry Foundation

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Is there any bit of popular philosophical wisdom more useless than the pseudo-Epictetian injunction to “live every day as if it were your last”? If today were my last, I certainly would not have just impulse-ordered an introductory grammar of Lithuanian. Much of what I do each day, in fact, is premised on the expectation that I will continue to do a little bit more of it the day after, and then the day after that, until I accomplish what is intrinsically a massively multi-day project. If I’ve only got one more day to do my stuff, well, the projects I reserve for that special day are hardly going to be the same ones (Lithuanian, Travis-style thumb-picking) by which I project myself, by which I throw myself towards the future. If today were my last day, I might still find time to churn out a quick ‘stack (no more than 5000 words) thanking you all for your loyal readership. But the noun-declension systems of the Baltic languages would probably be postponed for another life.

Is there any bit of popular philosophical wisdom more useless than the pseudo-Epictetian injunction to “live every day as if it were your last”? If today were my last, I certainly would not have just impulse-ordered an introductory grammar of Lithuanian. Much of what I do each day, in fact, is premised on the expectation that I will continue to do a little bit more of it the day after, and then the day after that, until I accomplish what is intrinsically a massively multi-day project. If I’ve only got one more day to do my stuff, well, the projects I reserve for that special day are hardly going to be the same ones (Lithuanian, Travis-style thumb-picking) by which I project myself, by which I throw myself towards the future. If today were my last day, I might still find time to churn out a quick ‘stack (no more than 5000 words) thanking you all for your loyal readership. But the noun-declension systems of the Baltic languages would probably be postponed for another life.

More here.

Bhaskar Sunkara in The Guardian:

It’s a nightmare we should have seen coming. In Germany, nuclear power formed around a third of the country’s power generation in 2000, when a Green party-spearheaded campaign managed to secure the gradual closure of plants, citing health and safety concerns. Last year, that share fell to 11%, with all remaining stations scheduled to close by next year. A recent paper found that the last two decades of phased nuclear closures led to an increase in CO2 emissions of 36.3 megatons a year – with the increased air pollution potentially killing 1,100 people annually.

It’s a nightmare we should have seen coming. In Germany, nuclear power formed around a third of the country’s power generation in 2000, when a Green party-spearheaded campaign managed to secure the gradual closure of plants, citing health and safety concerns. Last year, that share fell to 11%, with all remaining stations scheduled to close by next year. A recent paper found that the last two decades of phased nuclear closures led to an increase in CO2 emissions of 36.3 megatons a year – with the increased air pollution potentially killing 1,100 people annually.

Like New York, Germany coupled its transition away from nuclear power with a pledge to spend more aggressively on renewables. Yet the country’s first plant closures meant carbon emissions actually increased, as the production gap was immediately filled through the construction of new coal plants. Similarly, in New York the gap will be filled in part by the construction of three new gas plants.

More here.

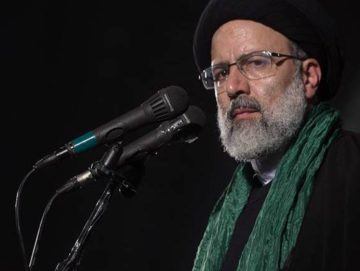

Abbas Milani in Project Syndicate:

Iran’s presidential election on June 18 was the most farcical in the history of the Islamic regime – even more so than the 2009 election, often called an “electoral coup.” It was less an election than a chronicle of a death foretold – the death of what little remained of the constitution’s republican principles. But, in addition to being the most farcical, the election may be the Islamic Republic’s most consequential.

Iran’s presidential election on June 18 was the most farcical in the history of the Islamic regime – even more so than the 2009 election, often called an “electoral coup.” It was less an election than a chronicle of a death foretold – the death of what little remained of the constitution’s republican principles. But, in addition to being the most farcical, the election may be the Islamic Republic’s most consequential.

The winner, Sayyid Ebrahim Raisi, is credibly accused of crimes against humanity for his role in killing some 4,000 dissidents three decades ago. Amnesty International has already called for him to be investigated for these crimes. Asked about the accusation, the new president-elect replied in a way that would have made even George Orwell blush, insisting that he should be praised for his defense of human rights in those murders.

Never has such a motley crew been chosen to act as a foil for its favored candidate. The regime mobilized all of its forces to ensure a big turnout for Raisi, who until the election was Iran’s chief justice. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei decreed voting a religious duty, and casting a blank ballot a sin, while his clerical allies condemned advocates of a boycott as heretics.

More here.

Philip Oltermann in The Guardian:

The name of the initiative was Project Cassandra: for the next two years, university researchers would use their expertise to help the German defence ministry predict the future.

The name of the initiative was Project Cassandra: for the next two years, university researchers would use their expertise to help the German defence ministry predict the future.

The academics weren’t AI specialists, or scientists, or political analysts. Instead, the people the colonels had sought out in a stuffy top-floor room were a small team of literary scholars led by Jürgen Wertheimer, a professor of comparative literature with wild curls and a penchant for black roll-necks.

More here.

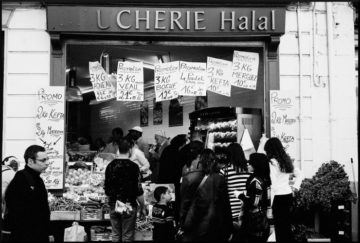

John Bowen in Boston Review:

Last October, while waging the government’s new campaign against Islamic forms of “separatism,” French Interior minister Gérald Darmanin complained on television that he was frequently “shocked” to enter a supermarket and see a shelf of “communalist food” (cuisine communautaire).

Last October, while waging the government’s new campaign against Islamic forms of “separatism,” French Interior minister Gérald Darmanin complained on television that he was frequently “shocked” to enter a supermarket and see a shelf of “communalist food” (cuisine communautaire).

Darmanin later expanded on his remarks, clarifying that he does not deny that people have a right to eat halal and kosher products (the “communalist foods” in question). He does, however, regret that capitalist profit-seekers advertised foods intended only for one segment of society in such a public way, and, even worse, in food shops patronized by all sorts of people. This, he contended, weakened the Republic by encouraging “separatism.” Of course, despite the intentional vagueness of the term “communalist,” few would have thought that the Minister had kosher pizzas in mind. Rather, he was signaling his annoyance at the myriad ways that—after hijabs in schools and on Decathalon jogging outfits—Muslims were again publicly holding back on their commitment to the Republic.

Darmanin’s remarks are but one version of a growing, broadly European complaint that halal food divides citizens, violates norms of animal welfare, and stealthily intrudes Islam into Western society. This complaint, and the measures that have begun to follow, shift depending on the post-colonial and anti-Islamic politics in each country. On this issue, politics is at once local, regional, and global. But why has access to religiously appropriate food assumed such political importance across Europe?

More here.

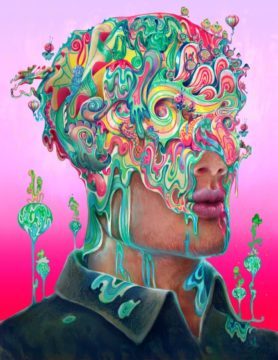

Oliver Sacks in The New Yorker:

To live on a day-to-day basis is insufficient for human beings; we need to transcend, transport, escape; we need meaning, understanding, and explanation; we need to see over-all patterns in our lives. We need hope, the sense of a future. And we need freedom (or, at least, the illusion of freedom) to get beyond ourselves, whether with telescopes and microscopes and our ever-burgeoning technology, or in states of mind that allow us to travel to other worlds, to rise above our immediate surroundings. We may seek, too, a relaxing of inhibitions that makes it easier to bond with each other, or transports that make our consciousness of time and mortality easier to bear. We seek a holiday from our inner and outer restrictions, a more intense sense of the here and now, the beauty and value of the world we live in.

To live on a day-to-day basis is insufficient for human beings; we need to transcend, transport, escape; we need meaning, understanding, and explanation; we need to see over-all patterns in our lives. We need hope, the sense of a future. And we need freedom (or, at least, the illusion of freedom) to get beyond ourselves, whether with telescopes and microscopes and our ever-burgeoning technology, or in states of mind that allow us to travel to other worlds, to rise above our immediate surroundings. We may seek, too, a relaxing of inhibitions that makes it easier to bond with each other, or transports that make our consciousness of time and mortality easier to bear. We seek a holiday from our inner and outer restrictions, a more intense sense of the here and now, the beauty and value of the world we live in.

Many of us find Wordsworthian “intimations of immortality” in nature, art, creative thinking, or religion; some people can reach transcendent states through meditation or similar trance-inducing techniques, or through prayer and spiritual exercises. But drugs offer a shortcut; they promise transcendence on demand. These shortcuts are possible because certain chemicals can directly stimulate many complex brain functions.

More here. (Note: From the archives)

Out there walking round, looking out for food,

a rootstock, a birdcall, a seed that you can crack

plucking, digging, snaring, snagging,

barely getting by,

no food out there on dusty slopes of scree—

carry some—look for some,

go for a hungry dream.

Deer bone, Dall sheep,

bones hunger home.

Out there somewhere

a shrine for the old ones,

the dust of the old bones,

old songs and tales.

What we ate—who ate what—

how we all prevailed.

by Gary Snyder

from Mountains and Rivers Without End

Counterpoint Press, 1996

Susannah Clapp at The Guardian:

Tove Jansson’s writing is different. She has wonderful passages in which entire landscapes are made by peering at blades of grass and scraps of bark. Yet her main Moomin adventures are startlingly catastrophic. For all the light clarity of the prose – which is comic, benign and quizzical – these books show places gripped by ferocious forces, laid waste by storms and floods and snows. They speak (but never obviously) of characters resonating to the winds and seas around them. They include visions that now read like warnings of climate change: “the great gap that had been the sea in front of them, the dark red sky overhead, and behind, the forest panting in the heat”.

Tove Jansson’s writing is different. She has wonderful passages in which entire landscapes are made by peering at blades of grass and scraps of bark. Yet her main Moomin adventures are startlingly catastrophic. For all the light clarity of the prose – which is comic, benign and quizzical – these books show places gripped by ferocious forces, laid waste by storms and floods and snows. They speak (but never obviously) of characters resonating to the winds and seas around them. They include visions that now read like warnings of climate change: “the great gap that had been the sea in front of them, the dark red sky overhead, and behind, the forest panting in the heat”.

There is some relish in these extremes: Jansson loved a storm and her island aesthetic is distinctive. Anti-lush, sculpted by the elements rather than softly shaped by a human hand. This is not like living in a garden.

more here.

Robert Gottlieb at the NYT:

Almost 75 years ago John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, “Inside U.S.A.” — more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish. It started out with a first printing of 125,000 copies — the largest first printing in the history of Harper & Brothers — plus 380,000 more for the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was the third-biggest nonfiction best seller of 1947 (ahead of it, only Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman’s “Peace of Mind” and the “Information Please Almanac”). It was a phenomenon, but not a surprise: Gunther’s first great success, “Inside Europe,” published in 1936, had helped alert the world to the realities of fascism and Stalinism; “Inside Asia” and “Inside Latin America” followed, with comparable success — all three of these books were among the top sellers of their year, as would be “Inside Africa” and “Inside Russia Today,” yet to come. His “Roosevelt in Retrospect” (1950) is one of the best political biographies I’ve ever come across, a mere 400 pages long and pure pleasure to read. Like “Inside U.S.A.,” it is out of print — please, American publishers, one of you make them reappear.

Almost 75 years ago John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, “Inside U.S.A.” — more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish. It started out with a first printing of 125,000 copies — the largest first printing in the history of Harper & Brothers — plus 380,000 more for the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was the third-biggest nonfiction best seller of 1947 (ahead of it, only Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman’s “Peace of Mind” and the “Information Please Almanac”). It was a phenomenon, but not a surprise: Gunther’s first great success, “Inside Europe,” published in 1936, had helped alert the world to the realities of fascism and Stalinism; “Inside Asia” and “Inside Latin America” followed, with comparable success — all three of these books were among the top sellers of their year, as would be “Inside Africa” and “Inside Russia Today,” yet to come. His “Roosevelt in Retrospect” (1950) is one of the best political biographies I’ve ever come across, a mere 400 pages long and pure pleasure to read. Like “Inside U.S.A.,” it is out of print — please, American publishers, one of you make them reappear.

more here.

Wolfgang Streeck in the New Left Review‘s Sidecar:

Wolfgang Streeck in the New Left Review‘s Sidecar:

On May 26, the Swiss government declared an end to year-long negotiations with the European Union on a so-called Institutional Framework Agreement that was to consolidate and extend the roughly one hundred bilateral treaties now regulating relations between the two sides. Negotiations began in 2014 and were concluded four years later, but Swiss domestic opposition got in the way of ratification. In subsequent years Switzerland sought reassurance essentially on four issues: permission to continue state assistance to its large and flourishing small business sector; immigration and the right to limit it to workers rather than having to admit all citizens of EU member states; protection of the (high) wages in the globally very successful Swiss export industries; and the jurisdiction, claimed by the EU, of the Court of Justice of the European Union over legal disagreements on the interpretation of joint treaties. As no progress was made, the prevailing impression in Switzerland became that the framework agreement was in fact to be a domination agreement, and as such too close to EU membership, which the Swiss had rejected in a national referendum in 1992 when they voted against joining the European Economic Area.

There are interesting parallels with the UK and Brexit. Both countries, in their different ways, have developed varieties of democracy distinguished by a deep commitment to a sort of majoritarian popular sovereignty that requires national sovereignty. This makes it difficult for them to enter into external relations that constrain the collective will-formation of their citizenry.

More here.

Matthieu Queloz in Aeon:

Matthieu Queloz in Aeon:

‘Ideas, Mr. Carlyle, ideas, nothing but ideas!’ scoffed a hard-headed businessman over dinner with Thomas Carlyle, the Victorian essayist and historian of the French Revolution. The businessman had had enough of Carlyle’s endless droning on about ideas – what do ideas matter anyway? Carlyle shot back: ‘There was once a man called Rousseau who wrote a book containing nothing but ideas. The second edition was bound in the skins of those who laughed at the first.’ Ideas have consequences.

Of course, Carlyle picked an easy case. He was referring to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s On the Social Contract (1762), a book brimming with incendiary political ideas that went on to fire up the leaders of the French Revolution. But the case for the practical importance of ideas is much harder to make for ideas that are more redolent of idle magniloquence than of revolutionary action. What of grand abstractions, with which our minds are stocked, such as knowledge, truth or justice? These are so entrenched that we can find it difficult to imagine doing without them. Yet it’s even more difficult to pin down just what useful practical difference they make to our lives. What exactly is the point of these ideas?

Unlike ideas of air, food and water that allow us to think about the everyday resources we need to survive, the venerable notions of knowledge, truth or justice don’t obviously cater to practical needs. On the contrary, these exalted ideals draw our gaze away from practical pursuits. They are imbued with grandeur precisely because of their superb indifference to mundane human concerns. Having knowledge is practically useful, but why would we also need the concept of knowledge? The dog who knows where his food is seems fine without the concept of knowledge, so long as he’s not called upon to give a commencement address. And yet the concepts of knowledge, truth or justice appear to have been important enough to emerge across different cultures and endure over the ages. Why, then, did we ever come to think in these terms?

More here.

Robert Pollin and Gerald Epstein in Boston Review:

Robert Pollin and Gerald Epstein in Boston Review:

The most basic tenet undergirding neoliberal economics is that free market capitalism—or at least some close approximation to it—is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. On this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes: big government spending and heavy regulations are simply less effective.

These neoliberal premises have dominated economic policymaking both in the United States and around the world for the past forty years, beginning with the elections of Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan in the States. Thatcher’s dictum that “there is no alternative” to neoliberalism became a rallying cry, supplanting what had been, since the end of World War II, the dominance of Keynesianism in global economic policymaking, which instead viewed large-scale government interventions as necessary for stability and a reasonable degree of fairness under capitalism. This neoliberal ascendency has been undergirded by the full-throated support of the overwhelming majority of professional economists, including such luminaries as Nobel Laureates Milton Friedman and Robert Lucas.

In reality neoliberalism has depended on huge levels of government support for its entire existence. The global neoliberal economic order could easily have collapsed into a 1930s-level Great Depression multiple times over in the absence of massive government interventions. Especially central to its survival have been government bailouts, including emergency government spending injections financed by borrowing—that is, deficit spending—as well as central bank actions to prop up financial institutions and markets teetering on the verge of ruin.

More here.

Paul J. D’Ambrosio in the LA Review of Books:

Paul J. D’Ambrosio in the LA Review of Books:

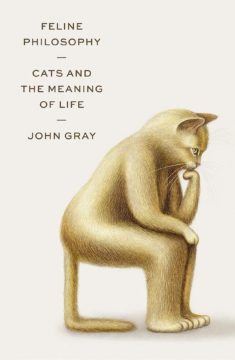

ACADEMIA PUTS SCHOLARS through the wringer. Few — very few, in fact — come out willing or even able to express complex ideas in ways appealing to non-academics. John Gray is one of those rare intellectuals.

Professors tend to scoff at books written for more general audiences. Anything that becomes popular is taken as potentially not serious. But the truth is, most professors simply cannot write, talk, and perhaps even think in a manner which can engage non-academics. Having gone through years of rigorous, specialized training, scholars find it hard to communicate their insights to anyone outside their narrow fields. Gray does not. Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life is broadly appealing. Even more impressive, it has readers seriously consider radical ideas.

It is difficult to speak about the myth of human progress, the navel-gazing silliness of autonomy and reason, the pompous attitude of the righteous, and the associated paradoxical nature of morality, accepting that neither love nor death are really such a big deal and — this is the real point of the book — the meaninglessness of the meaning of life. Gray does so without strong arguments, logical deductions, or other conventional philosophical tools. Big-name philosophers are referenced, but mostly on the back of novels about cats. Intertwining stories and facts about cats with philosophy, Gray invites serious reflection without telling readers how to reason or what to think.

More here.

Mandy Oaklander in Time Magazine:

Amber Capone had become afraid of her husband. The “laid-back, bigger than life and cooler than cool” man she’d married had become isolated, disconnected and despondent during his 13 years as a U.S. Navy SEAL. Typically, he was gone 300 days of the year, but when he was home, Amber and their two children walked on eggshells around him. “Everyone was just playing nice until he left again,” Amber says.

Amber Capone had become afraid of her husband. The “laid-back, bigger than life and cooler than cool” man she’d married had become isolated, disconnected and despondent during his 13 years as a U.S. Navy SEAL. Typically, he was gone 300 days of the year, but when he was home, Amber and their two children walked on eggshells around him. “Everyone was just playing nice until he left again,” Amber says.

In 2013, Marcus retired from the military. But life as a civilian only made his depression, anger, headaches, anxiety, alcoholism, impulsivity and violent dreams worse. Sometimes he’d get upset by noon and binge-drink for 12 hours. Amber watched in horror as his cognitive functioning declined; Marcus was in his late 30s, but he would get lost driving his daughter to volleyball, and sometimes he couldn’t even recognize his friends. Psychologists had diagnosed him with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety, but antidepressants, Ambien and Adderall didn’t help. He visited a handful of brain clinics across the country, which diagnosed him with postconcussive syndrome after a childhood of football—then a career punctuated by grenades, explosives, rifles and shoulder-fired rockets. But all they offered were more pills, none of which helped either.

Marcus wasn’t the only one suffering in his tight-knit community of Navy SEALs and special-operations veterans. A close friend killed himself, and Amber knew her husband could be next. “I truly thought that Marcus would be the one having the suicide funeral,” Amber says.

There was one last option.

More here.