Wouter Klein at JSTOR Daily:

When European naturalists explored the plants of the New World in the sixteenth century, they tended to relate new species to better-known plants whenever they could. Sarsaparilla is a case in point. Smilax species found in America were recognized as variants of Smilax aspera and therefore also began to be called sarsaparilla. Nicolás Monardes (1493–1588) described different kinds of American sarsaparilla in his work Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales (1565). His descriptions carried a commercial touch. For instance, he tried to convince his readers that the whitish sarsaparilla from Honduras was better than the black variety from Mexico. Similarly, he aimed to embed the new American kinds of sarsaparilla in the traditional framework of European medicine. When American sarsaparilla began to be used in European medicine around 1545, physicians first administered it as a broth to be taken in the morning, the same way as it was used by Native Americans at the time. Monardes, however, argued that it should be given in a syrup, a conventional mode of administration for his European readers.

When European naturalists explored the plants of the New World in the sixteenth century, they tended to relate new species to better-known plants whenever they could. Sarsaparilla is a case in point. Smilax species found in America were recognized as variants of Smilax aspera and therefore also began to be called sarsaparilla. Nicolás Monardes (1493–1588) described different kinds of American sarsaparilla in his work Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales (1565). His descriptions carried a commercial touch. For instance, he tried to convince his readers that the whitish sarsaparilla from Honduras was better than the black variety from Mexico. Similarly, he aimed to embed the new American kinds of sarsaparilla in the traditional framework of European medicine. When American sarsaparilla began to be used in European medicine around 1545, physicians first administered it as a broth to be taken in the morning, the same way as it was used by Native Americans at the time. Monardes, however, argued that it should be given in a syrup, a conventional mode of administration for his European readers.

more here.

A painful pattern repeats itself throughout America: A Black person is killed by police officers, protests ensue, and police are brought in to stifle the demonstrations. Most of the time, the protests against racial injustice are peaceful, but occasionally violence breaks out. Meanwhile, politicians do little to prevent the cycle from continuing.

A painful pattern repeats itself throughout America: A Black person is killed by police officers, protests ensue, and police are brought in to stifle the demonstrations. Most of the time, the protests against racial injustice are peaceful, but occasionally violence breaks out. Meanwhile, politicians do little to prevent the cycle from continuing. Proteins have been quietly taking over our lives since the COVID-19 pandemic began. We’ve been living at the whim of the virus’s so-called “spike” protein, which has mutated dozens of times to create increasingly deadly variants. But the truth is, we have always been ruled by proteins. At the cellular level, they’re responsible for pretty much everything.

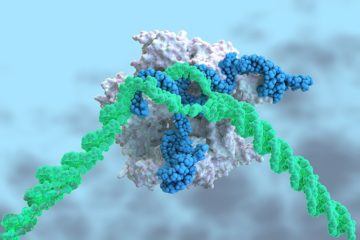

Proteins have been quietly taking over our lives since the COVID-19 pandemic began. We’ve been living at the whim of the virus’s so-called “spike” protein, which has mutated dozens of times to create increasingly deadly variants. But the truth is, we have always been ruled by proteins. At the cellular level, they’re responsible for pretty much everything. Academia puts scholars through the wringer. Few — very few, in fact — come out willing or even able to express complex ideas in ways appealing to non-academics. John Gray is one of those rare intellectuals.

Academia puts scholars through the wringer. Few — very few, in fact — come out willing or even able to express complex ideas in ways appealing to non-academics. John Gray is one of those rare intellectuals. The most basic tenet undergirding neoliberal economics is that free market capitalism—or at least some close approximation to it—is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. On this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes: big government spending and heavy regulations are simply less effective.

The most basic tenet undergirding neoliberal economics is that free market capitalism—or at least some close approximation to it—is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. On this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes: big government spending and heavy regulations are simply less effective. The most haunting thing about

The most haunting thing about  In his new book, “

In his new book, “ Preliminary results from a landmark clinical trial suggest that CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing can be deployed directly into the body to treat disease. The study is the first to show that the technique can be safe and effective if the CRISPR–Cas9 components — in this case targeting a protein that is made mainly in the liver — are infused into the bloodstream. In the trial, six people with a rare and fatal condition called transthyretin amyloidosis received a single treatment with the gene-editing therapy. All experienced a drop in the level of a misshapen protein associated with the disease. Those who received the higher of two doses tested saw levels of the protein, called TTR, decline by an average of 87%.

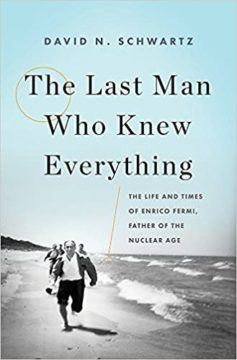

Preliminary results from a landmark clinical trial suggest that CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing can be deployed directly into the body to treat disease. The study is the first to show that the technique can be safe and effective if the CRISPR–Cas9 components — in this case targeting a protein that is made mainly in the liver — are infused into the bloodstream. In the trial, six people with a rare and fatal condition called transthyretin amyloidosis received a single treatment with the gene-editing therapy. All experienced a drop in the level of a misshapen protein associated with the disease. Those who received the higher of two doses tested saw levels of the protein, called TTR, decline by an average of 87%. A long time ago, when I was around the age my kids are now— so if you were to ask them, that’d put it well after the dinosaurs but slightly before woolly mammoths— I had to write a book report about a biography. For whatever reason, I ended up picking Enrico Fermi, a scientist who was featured in exactly one book in the elementary school library, a choice that maybe foreshadowed my eventual career. A few details of that have stuck with me ever since: Fermi getting reprimanded by Oppenheimer for taking bets on whether the Trinity test would ignite the atmosphere, Fermi estimating the size of the blast by dropping pieces of paper, and, weirdly, Fermi mocking signs with Fascist slogans back in Italy by shouting “Burma Shave!” when driving past them (probably because I had to get my parents to explain the joke). I was a little hazy on what, exactly, he contributed to physics, but he definitely made an impression as both an important scientist and a colorful character.

A long time ago, when I was around the age my kids are now— so if you were to ask them, that’d put it well after the dinosaurs but slightly before woolly mammoths— I had to write a book report about a biography. For whatever reason, I ended up picking Enrico Fermi, a scientist who was featured in exactly one book in the elementary school library, a choice that maybe foreshadowed my eventual career. A few details of that have stuck with me ever since: Fermi getting reprimanded by Oppenheimer for taking bets on whether the Trinity test would ignite the atmosphere, Fermi estimating the size of the blast by dropping pieces of paper, and, weirdly, Fermi mocking signs with Fascist slogans back in Italy by shouting “Burma Shave!” when driving past them (probably because I had to get my parents to explain the joke). I was a little hazy on what, exactly, he contributed to physics, but he definitely made an impression as both an important scientist and a colorful character. Depending on who you listen to, quantum computers are either the biggest technological change coming down the road or just another overhyped bubble. Today we’re talking with a good person to listen to: John Preskill, one of the leaders in modern quantum information science. We talk about what a quantum computer is and promising technologies for actually building them. John emphasizes that quantum computers are tailor-made for simulating the behavior of quantum systems like molecules and materials; whether they will lead to breakthroughs in cryptography or optimization problems is less clear. Then we relate the idea of quantum information back to gravity and the emergence of spacetime. (If you want to build and run your own quantum algorithm, try the

Depending on who you listen to, quantum computers are either the biggest technological change coming down the road or just another overhyped bubble. Today we’re talking with a good person to listen to: John Preskill, one of the leaders in modern quantum information science. We talk about what a quantum computer is and promising technologies for actually building them. John emphasizes that quantum computers are tailor-made for simulating the behavior of quantum systems like molecules and materials; whether they will lead to breakthroughs in cryptography or optimization problems is less clear. Then we relate the idea of quantum information back to gravity and the emergence of spacetime. (If you want to build and run your own quantum algorithm, try the  The law has failed Britney Spears. The nearly 40-year-old celebrity has been locked in a “conservatorship”—which is the state of California’s word for a “legal guardianship” designed for the very old, very young, or mentally incapacitated—for 13 years, against her will. That conservatorship, controlled by her father, again, against her will, has been allowed to control Spears’s life in minute detail—including allegedly forcing unwanted birth control upon her—and none of the lawyers or judges involved has done a damn thing to stop it. Spears appeared in court, via telephone, this week to voice her objections to her continued conservatorship, and her story should lead to immediate lawmaking and change.

The law has failed Britney Spears. The nearly 40-year-old celebrity has been locked in a “conservatorship”—which is the state of California’s word for a “legal guardianship” designed for the very old, very young, or mentally incapacitated—for 13 years, against her will. That conservatorship, controlled by her father, again, against her will, has been allowed to control Spears’s life in minute detail—including allegedly forcing unwanted birth control upon her—and none of the lawyers or judges involved has done a damn thing to stop it. Spears appeared in court, via telephone, this week to voice her objections to her continued conservatorship, and her story should lead to immediate lawmaking and change. The two dialectical modes—call them determinate and indeterminate negation—are unevenly distributed throughout Fried’s work. (There is probably more to be said about that.) From the standpoint of Jacques-Louis David’s Intervention of the Sabine Women, the approach he had taken in Oath of the Horatii just over a decade earlier appears as superseded. But while Rineke Dijkstra’s bathers mobilize facingness and an awareness of the camera, there is no sense in Fried’s interpretation of them that they supersede, negate, or critique Andreas Gursky’s preference for figures that are oblivious to the camera or viewed from behind. One can imagine formulating a claim that Dijkstra’s bathers do in fact represent an advance over some of Gursky’s pictures—a deepening or reduplication of the photographic tension between automatism and intention—but that would be an additional claim, beyond the essentially dialectical one that the two photographers are working in the context of a self-critical normative or institutional field; that both artists are engaged in confronting a problem or contradiction that is understood to be constitutive of photography itself, a “hidden motor” of dialectical development (AO 50). Dialectical movement can be expansive or lateral—even rhizomatic (“well-grubbed”)—as well as determinately directional.

The two dialectical modes—call them determinate and indeterminate negation—are unevenly distributed throughout Fried’s work. (There is probably more to be said about that.) From the standpoint of Jacques-Louis David’s Intervention of the Sabine Women, the approach he had taken in Oath of the Horatii just over a decade earlier appears as superseded. But while Rineke Dijkstra’s bathers mobilize facingness and an awareness of the camera, there is no sense in Fried’s interpretation of them that they supersede, negate, or critique Andreas Gursky’s preference for figures that are oblivious to the camera or viewed from behind. One can imagine formulating a claim that Dijkstra’s bathers do in fact represent an advance over some of Gursky’s pictures—a deepening or reduplication of the photographic tension between automatism and intention—but that would be an additional claim, beyond the essentially dialectical one that the two photographers are working in the context of a self-critical normative or institutional field; that both artists are engaged in confronting a problem or contradiction that is understood to be constitutive of photography itself, a “hidden motor” of dialectical development (AO 50). Dialectical movement can be expansive or lateral—even rhizomatic (“well-grubbed”)—as well as determinately directional. “L

“L In “Visible Republic,” his essay on Dylan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, Robbins extracts himself from the pro/con squad and tries to isolate the nature of the songwriter (rather than isolate the most literary thing about Dylan because what would that be?). “That’s it, that’s the thing—Dylan isn’t words,” Robbins writes. “He’s words plus [Robbie] Robertson’s uncanny awk, drummer Levon Helm’s cephalopodic clatter, the thin, wild mercury of his voice.” Meaning, one thinks, that by all means win some prizes, who cares, but don’t make one form do another’s work. This exhibits the generosity in both Robbins’s poems and essays. The glittering trash of the world needs itemizing but not sorting. His essay on

In “Visible Republic,” his essay on Dylan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, Robbins extracts himself from the pro/con squad and tries to isolate the nature of the songwriter (rather than isolate the most literary thing about Dylan because what would that be?). “That’s it, that’s the thing—Dylan isn’t words,” Robbins writes. “He’s words plus [Robbie] Robertson’s uncanny awk, drummer Levon Helm’s cephalopodic clatter, the thin, wild mercury of his voice.” Meaning, one thinks, that by all means win some prizes, who cares, but don’t make one form do another’s work. This exhibits the generosity in both Robbins’s poems and essays. The glittering trash of the world needs itemizing but not sorting. His essay on  Three decades ago, a small group from within the AIDS activist organization ACT UP changed the course of medicine in the United States. They employed what they called “the outside/inside strategy.” The activists staged large, noisy demonstrations outside the Food and Drug Administration and other federal government agencies, demanding an acceleration of the drug-approval process. Others learned the minutiae of the science and worked quietly with receptive bureaucrats, bringing the patient’s perspective to the table toward the same goal of faster drug approval. These were desperate young people dying from a new disease for which there were few treatments and no cure. At first, federal bureaucrats and drug companies resisted, but eventually more AIDS drugs became available.

Three decades ago, a small group from within the AIDS activist organization ACT UP changed the course of medicine in the United States. They employed what they called “the outside/inside strategy.” The activists staged large, noisy demonstrations outside the Food and Drug Administration and other federal government agencies, demanding an acceleration of the drug-approval process. Others learned the minutiae of the science and worked quietly with receptive bureaucrats, bringing the patient’s perspective to the table toward the same goal of faster drug approval. These were desperate young people dying from a new disease for which there were few treatments and no cure. At first, federal bureaucrats and drug companies resisted, but eventually more AIDS drugs became available.