Emily Bazelon in the New York Times:

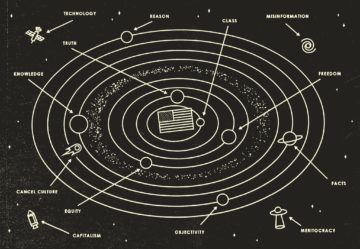

Like many public intellectuals who are worth reading, George Packer and Jonathan Rauch don’t toe a predictable line in American political and intellectual debate. They despise Donald Trump and the disinformation-heavy discord he has spawned. But they don’t share all the views of progressives, either, as they’ve come to be defined in many left-leaning spaces. Packer and Rauch are here to defend the liberalism of the Enlightenment — equality and scientific rationality in an unapologetically Western-tradition sense. They see this belief system as the country’s great and unifying strength, and they’re worried about its future.

Like many public intellectuals who are worth reading, George Packer and Jonathan Rauch don’t toe a predictable line in American political and intellectual debate. They despise Donald Trump and the disinformation-heavy discord he has spawned. But they don’t share all the views of progressives, either, as they’ve come to be defined in many left-leaning spaces. Packer and Rauch are here to defend the liberalism of the Enlightenment — equality and scientific rationality in an unapologetically Western-tradition sense. They see this belief system as the country’s great and unifying strength, and they’re worried about its future.

Packer’s slim book, “Last Best Hope,” begins with patriotic despair. “The world’s pity has taken the place of admiration, hostility, awe, envy, fear, affection and repulsion,” he writes of the perception of the United States abroad. This might have rung true in the throes of the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, which may also be when it was written, but it now sounds overwrought. So does Packer’s claim that “a lot of Americans have explored their options for expatriation.” (The number of expatriates is rising but small, and the cause of the uptick is likely a change in tax law, according to The Wall Street Journal.)

Once Packer gets going, however, he is forceful.

More here.

In Akwaeke Emezi’s new book,

In Akwaeke Emezi’s new book,  O

O Marco D’Eramo in The New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Marco D’Eramo in The New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Frankie Thomas in The Paris Review:

Frankie Thomas in The Paris Review: W-3, Bette Howland’s memoir of her stay in a psychiatric hospital following an overdose, was first published in 1974, and comes to us now following the reissue, last year, of her 1978 collection of stories,

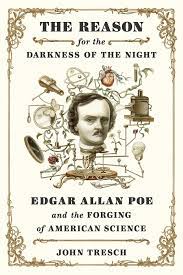

W-3, Bette Howland’s memoir of her stay in a psychiatric hospital following an overdose, was first published in 1974, and comes to us now following the reissue, last year, of her 1978 collection of stories,  Is Poe really the most influential American writer? Note that I didn’t say “greatest,” for which there must be at least a dozen viable candidates. But consider his radiant originality. Before his death in 1849 at age 40, Poe largely created the modern short story, while also inventing or perfecting half the genres represented on the bestseller list, including the mystery (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Gold-Bug”), science fiction (“The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion”), psychological suspense (“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Cask of Amontillado”) and, of course, gothic horror (“The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” the incomparable “Ligeia”).

Is Poe really the most influential American writer? Note that I didn’t say “greatest,” for which there must be at least a dozen viable candidates. But consider his radiant originality. Before his death in 1849 at age 40, Poe largely created the modern short story, while also inventing or perfecting half the genres represented on the bestseller list, including the mystery (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Gold-Bug”), science fiction (“The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion”), psychological suspense (“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Cask of Amontillado”) and, of course, gothic horror (“The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” the incomparable “Ligeia”). When I’m stuck—and I’m stuck all the time—I look at “

When I’m stuck—and I’m stuck all the time—I look at “ T

T WILLIAM LOGAN: I doubt critics of a critical temper are dying out, but grumpy critics rarely remain grumpy very long. John Simon, whose temperament even I sometimes found captious, was still growling into his 90s. A number of critics of my generation and the generation after came out roaring in their 20s but stopped writing criticism within a decade. Critics who fail to go along to get along are punished, supposedly. It may not be entirely untrue — I’ve been told twice that I was on track to win some small award, which went sideways when one of the judges raged about my criticism. If that’s the punishment the world metes out, it’s a revenge small and pathetic — and hilarious.

WILLIAM LOGAN: I doubt critics of a critical temper are dying out, but grumpy critics rarely remain grumpy very long. John Simon, whose temperament even I sometimes found captious, was still growling into his 90s. A number of critics of my generation and the generation after came out roaring in their 20s but stopped writing criticism within a decade. Critics who fail to go along to get along are punished, supposedly. It may not be entirely untrue — I’ve been told twice that I was on track to win some small award, which went sideways when one of the judges raged about my criticism. If that’s the punishment the world metes out, it’s a revenge small and pathetic — and hilarious. The

The  I was startled when the phone rang while I was shaving. It was 7 am. The press attaché for Giorgio Armani called me in my Milan hotel room to tell me the designer wanted to have dinner with me that night. It was more a summons than an invitation. Mr. Armani was the sacred cow, the designer Mr. Fairchild was enthralled with, which is why almost all of his senior editors in New York City wore only Armani’s clothing—purchased with generous press discounts supplemented by the occasional, ostensibly forbidden unreported gift.

I was startled when the phone rang while I was shaving. It was 7 am. The press attaché for Giorgio Armani called me in my Milan hotel room to tell me the designer wanted to have dinner with me that night. It was more a summons than an invitation. Mr. Armani was the sacred cow, the designer Mr. Fairchild was enthralled with, which is why almost all of his senior editors in New York City wore only Armani’s clothing—purchased with generous press discounts supplemented by the occasional, ostensibly forbidden unreported gift.