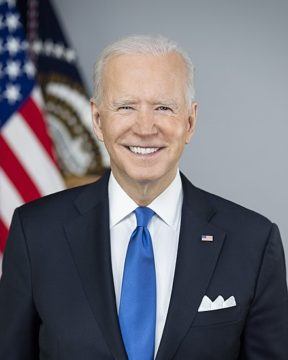

Cedric Durand in Sidecar:

The extent of the break with neoliberalism initiated by the Biden administration will depend upon both the unfolding of Washingtonian politics and the impact of mobilizations from below. Yet in the background, impersonal forces will continue to affect the metamorphosis of capitalism through its successive stages. It is from these structural constraints and opportunities that the fabric of the current conjuncture is woven. What can contemporary political economy tell us about them? Beyond the sphere of mainstream liberal thought, an array of recent theoretical contributions have tried to diagnose the current moment by situating it in the long-term rhythms of capitalist development. They offer a fresh light, if not a magic key, for understanding the systemic shift represented by Bidenomics.

Such forces of change are routinely ignored by liberal economists. Market exchange is viewed as a sphere of activity that depends solely on itself; conscious collective intervention must not interfere with the invisible hand or spontaneous order. However, it is increasingly clear that this faith in self-equilibrating market adjustment cannot provide a general theory of rapid socioeconomic change, nor a specific explanation of our present political turbulence. Recognizing this limitation, The Economist recently rejected neoclassical equilibrium modelling and Friedmanite instrumentalism in favour of evolutionary economics, which ‘seeks to explain real-world phenomena as the outcome of a process of continuous change’. ‘The past informs the present’, it declared. ‘Economic choices are made within and informed by historical, cultural and institutional contexts’.

This intervention signals the weakened grip of neoclassical economics on the profession as a whole. Yet the evolutionary schema nonetheless retains a deep loyalty to bourgeois ideology, premised on the belief that Natura non facit saltum, ‘nature does not make jumps’. For this school of thought, evolution is always incremental.

More here.

Adam Tooze in the New Statesman:

Adam Tooze in the New Statesman: A

A Jinny: How do the topics of language and writing in the novel reinforce and strengthen Dagestani identity?

Jinny: How do the topics of language and writing in the novel reinforce and strengthen Dagestani identity? What makes Twitter so axiomatically hellish? It’s a place where even the most well-intentioned attempts at intellectually honest conversation inevitably devolve into misunderstanding and mutual contempt, like the fruit that crumbles into ash in the devils’ mouths in book 10 of Paradise Lost. It amplifies our simultaneous interdependency and alienation, the overtaking of meaningful political life by the triviality of the social. It is other people. But mostly Twitter is Hell because we—a “we” that, in Twitter’s universalizing idiom, outstretches optimistically or threateningly as if to envelop even those blessed souls who have never once logged on—make it so. It’s our own personal Hell, algorithmically articulated and given back to us, customized enough that I can complain to another very online friend about something that’s “all over Twitter” and he can reply, in confusion, “hmm, not my Twitter,” but shared enough that another friend can affirm, “on my Twitter too.” Pathetic fallacy subtends the most viral memes, either on the individual level (“it me”) or from the perspective of the willed collective of Twitter itself.

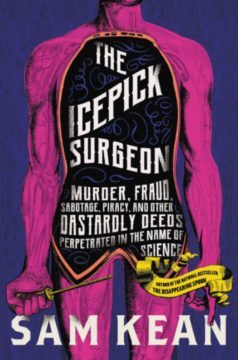

What makes Twitter so axiomatically hellish? It’s a place where even the most well-intentioned attempts at intellectually honest conversation inevitably devolve into misunderstanding and mutual contempt, like the fruit that crumbles into ash in the devils’ mouths in book 10 of Paradise Lost. It amplifies our simultaneous interdependency and alienation, the overtaking of meaningful political life by the triviality of the social. It is other people. But mostly Twitter is Hell because we—a “we” that, in Twitter’s universalizing idiom, outstretches optimistically or threateningly as if to envelop even those blessed souls who have never once logged on—make it so. It’s our own personal Hell, algorithmically articulated and given back to us, customized enough that I can complain to another very online friend about something that’s “all over Twitter” and he can reply, in confusion, “hmm, not my Twitter,” but shared enough that another friend can affirm, “on my Twitter too.” Pathetic fallacy subtends the most viral memes, either on the individual level (“it me”) or from the perspective of the willed collective of Twitter itself. Walter Freeman was

Walter Freeman was Part of the problem is that English spelling looks deceptively similar to other languages that use the same alphabet but in a much more consistent way. You can spend an afternoon familiarising yourself with the pronunciation rules of Italian, Spanish, German, Swedish, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish and many others, and credibly read out a text in that language, even if you don’t understand it. Your pronunciation might be terrible, and the pace, stress and rhythm would be completely off, and no one would mistake you for a native speaker – but you could do it. Even French, notorious for the spelling challenges it presents learners, is consistent enough to meet the bar. There are lots of silent letters, but they’re in predictable places. French has plenty of rules, and exceptions to those rules, but they can all be listed on a reasonable number of pages.

Part of the problem is that English spelling looks deceptively similar to other languages that use the same alphabet but in a much more consistent way. You can spend an afternoon familiarising yourself with the pronunciation rules of Italian, Spanish, German, Swedish, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish and many others, and credibly read out a text in that language, even if you don’t understand it. Your pronunciation might be terrible, and the pace, stress and rhythm would be completely off, and no one would mistake you for a native speaker – but you could do it. Even French, notorious for the spelling challenges it presents learners, is consistent enough to meet the bar. There are lots of silent letters, but they’re in predictable places. French has plenty of rules, and exceptions to those rules, but they can all be listed on a reasonable number of pages.

In hindsight, it was only fitting that a story about surveillance and spyware in India should have begun with more than a touch of cloak and dagger.

In hindsight, it was only fitting that a story about surveillance and spyware in India should have begun with more than a touch of cloak and dagger. In a 1959 letter to her friend Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt paused to commiserate on a harrowing experience they had in common: having their writing fact-checked by The New Yorker. In her previous correspondence, McCarthy had mused that the magazine’s checking department was “invented by some personal Prosecutor of mine to shatter the morale,” and Arendt shared her frustration. Fact-checking, she replied, was a “kind of torture,” a “rigmarole,” and “one of the many forms in which the would-be writers persecute the writer.” Arendt’s opposition to the practice of fact-checking ran deeper than personal irritation. Throughout her work, she was critical of the infiltration of scientific terminology and methods into all aspects of human life. Couching an argument in language that sounded scientific, she thought, was a way of claiming the ability to know or predict things that could never be predicted or known. Fact-checking was a part of that larger trend: the practice, she wrote to McCarthy, was a form of “phony scientificality.”

In a 1959 letter to her friend Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt paused to commiserate on a harrowing experience they had in common: having their writing fact-checked by The New Yorker. In her previous correspondence, McCarthy had mused that the magazine’s checking department was “invented by some personal Prosecutor of mine to shatter the morale,” and Arendt shared her frustration. Fact-checking, she replied, was a “kind of torture,” a “rigmarole,” and “one of the many forms in which the would-be writers persecute the writer.” Arendt’s opposition to the practice of fact-checking ran deeper than personal irritation. Throughout her work, she was critical of the infiltration of scientific terminology and methods into all aspects of human life. Couching an argument in language that sounded scientific, she thought, was a way of claiming the ability to know or predict things that could never be predicted or known. Fact-checking was a part of that larger trend: the practice, she wrote to McCarthy, was a form of “phony scientificality.” A

A Oscar Wilde’s ship docked in New York Harbor on the evening of January 2, 1882, one week before he was scheduled to speak at Chickering Hall. During the crossing he had composed his first lecture, but the journalists who swarmed onto the ship as it lay at anchor off Staten Island were more interested in Wilde himself than in the theories he had come to expound. “His outer garment was a long ulster trimmed with two kinds of fur, which reached almost to his feet,” reported the New York World; “he wore patent-leather shoes, a smoking-cap or turban, and his shirt might be termed ultra-Byronic . . . His hair flowed over his shoulders in dark-brown waves, curling slightly upwards at the ends . . . His teeth were large and regular, disproving a pleasing story which has gone the rounds of the English press that he has three tusks or protuberants.” His face presented “an exaggerated oval of the Italian face carried into the English type of countenance,” the World reporter continued, while his “manner of talking” was “somewhat affected . . . his great peculiarity being a rhythmical chant in which every fourth syllable is accentuated.” “The dress of the poet was not less remarkable than his face,” declared the San Francisco Chronicle, “and consisted of a short velvet coat, rose-colored necktie and dark-brown trousers . . . cut with a sublime disregard of the latest fashion.”

Oscar Wilde’s ship docked in New York Harbor on the evening of January 2, 1882, one week before he was scheduled to speak at Chickering Hall. During the crossing he had composed his first lecture, but the journalists who swarmed onto the ship as it lay at anchor off Staten Island were more interested in Wilde himself than in the theories he had come to expound. “His outer garment was a long ulster trimmed with two kinds of fur, which reached almost to his feet,” reported the New York World; “he wore patent-leather shoes, a smoking-cap or turban, and his shirt might be termed ultra-Byronic . . . His hair flowed over his shoulders in dark-brown waves, curling slightly upwards at the ends . . . His teeth were large and regular, disproving a pleasing story which has gone the rounds of the English press that he has three tusks or protuberants.” His face presented “an exaggerated oval of the Italian face carried into the English type of countenance,” the World reporter continued, while his “manner of talking” was “somewhat affected . . . his great peculiarity being a rhythmical chant in which every fourth syllable is accentuated.” “The dress of the poet was not less remarkable than his face,” declared the San Francisco Chronicle, “and consisted of a short velvet coat, rose-colored necktie and dark-brown trousers . . . cut with a sublime disregard of the latest fashion.” Two decades after the draft sequence of the human genome was

Two decades after the draft sequence of the human genome was  A new study tracking the planet’s vital signs has found that many of the key indicators of the global climate crisis are getting worse and either approaching, or exceeding, key tipping points as the earth heats up.

A new study tracking the planet’s vital signs has found that many of the key indicators of the global climate crisis are getting worse and either approaching, or exceeding, key tipping points as the earth heats up.