Benjamin Taylor in The Atlantic:

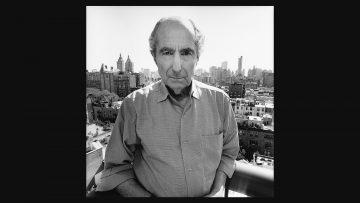

Delirious near the end, he said, “We’re going to the Savoy!”—surely the jauntiest dying words on record. But it was Riverside Memorial Chapel, the Jewish funeral parlor at Amsterdam and 76th, that we were bound for. I was obliged to reidentify the body once we arrived there from New York–Presbyterian Hospital. An undertaker pointed the way to the viewing room and said, “You may stay for as long as you like. But do not touch him.” Duly draped, Philip looked serene on his plinth—like a Roman emperor, one of the good ones. I pulled up a chair and managed to say, “Here we are.” Here we are at the promised end. A phrase from The Human Stain came to me: “the dignity of an elderly gentleman free from desire who behaves correctly.” I wanted to tell him that he was doing fine, that he was a champ at being dead, bringing to it all the professionalism he’d brought to previous tasks. To talk daily with someone of such gifts had been a salvation. There was no dramatic arc to our life together. It was not like a marriage, still less like a love affair. It was as plotless as friendship ought to be. We spent thousands of hours in each other’s company. I’m not who I would have been without him. “We’ve laughed so hard,” he said to me some years ago. “Maybe write a book about our friendship.”

Delirious near the end, he said, “We’re going to the Savoy!”—surely the jauntiest dying words on record. But it was Riverside Memorial Chapel, the Jewish funeral parlor at Amsterdam and 76th, that we were bound for. I was obliged to reidentify the body once we arrived there from New York–Presbyterian Hospital. An undertaker pointed the way to the viewing room and said, “You may stay for as long as you like. But do not touch him.” Duly draped, Philip looked serene on his plinth—like a Roman emperor, one of the good ones. I pulled up a chair and managed to say, “Here we are.” Here we are at the promised end. A phrase from The Human Stain came to me: “the dignity of an elderly gentleman free from desire who behaves correctly.” I wanted to tell him that he was doing fine, that he was a champ at being dead, bringing to it all the professionalism he’d brought to previous tasks. To talk daily with someone of such gifts had been a salvation. There was no dramatic arc to our life together. It was not like a marriage, still less like a love affair. It was as plotless as friendship ought to be. We spent thousands of hours in each other’s company. I’m not who I would have been without him. “We’ve laughed so hard,” he said to me some years ago. “Maybe write a book about our friendship.”

Our conversation was about everything—novels, politics, families, dreams, sex, baseball, food, ex-friends, ex-lovers. Philip’s inner life was gargantuan. Insatiable emotional appetites—for rage as for love—led him down paths where he seethed with loathing or desire. “There’s too much of you, Philip. All your emotions are outsize,” I once said to him. “I’ve written in order not to die of them,” he replied. But our keynote was American history, for which Philip was ravenous, consuming one big scholarly book after another. He became a great writer over the course of the 1980s and especially the ’90s, when his novels became history-haunted. In the American trilogy—American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain—the heroes, Swede Levov, Ira Ringold, and Coleman Silk, are solid men torn to pieces when the blindsiding force of history comes to call. Such was Philip’s mature theme: the unpredictable brutalities at large in the world and the illusoriness of ever being safe from them. He never stopped marveling at how contingently a fate is made. For him, that was most basic to storytelling: the happenstance that in retrospect turns epic.

More here.