Jill Lepore in The New Yorker:

Facebook has a save-the-world mission statement—“to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together”—that sounds like a better fit for a church, and not some little wood-steepled, white-clapboarded, side-of-the-road number but a castle-in-a-parking-lot megachurch, a big-as-a-city-block cathedral, or, honestly, the Vatican. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s C.E.O., announced this mission the summer after the 2016 U.S. Presidential election, replacing the company’s earlier and no less lofty purpose: “to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.” Both versions, like most mission statements, are baloney.

Facebook has a save-the-world mission statement—“to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together”—that sounds like a better fit for a church, and not some little wood-steepled, white-clapboarded, side-of-the-road number but a castle-in-a-parking-lot megachurch, a big-as-a-city-block cathedral, or, honestly, the Vatican. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s C.E.O., announced this mission the summer after the 2016 U.S. Presidential election, replacing the company’s earlier and no less lofty purpose: “to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.” Both versions, like most mission statements, are baloney.

The word “mission” comes from the Latin for “send.” In English, historically, a mission is Christian, and means sending the Holy Spirit out into the world to spread the Word of God: a mission involves saving souls. In the seventeenth century, when “mission” first conveyed something secular, it meant diplomacy: emissaries undertake missions. Scientific and military missions—and the expression “mission accomplished”—date to about the First World War. In 1962, J.F.K. called going to the moon an “untried mission.” “Mission statements” date to the Vietnam War, when the Joint Chiefs of Staff began drafting ever-changing objectives for a war known for its purposelessness. (The TV show “Mission: Impossible” débuted in 1966.) After 1973, and at the urging of the management guru Peter Drucker, businesses started writing mission statements as part of the process of “strategic planning,” another expression Drucker borrowed from the military. Before long, as higher education was becoming corporatized, mission statements crept into university life. “We are on the verge of mission madness,” the Chronicle of Higher Education reported in 1979. A decade later, a management journal announced, “Developing a mission statement is an important first step in the strategic planning process.” But by the nineteen-nineties corporate mission statements had moved from the realm of strategic planning to public relations. That’s a big part of why they’re bullshit. One study from 2002 reported that most managers don’t believe their own companies’ mission statements. Research surveys suggest a rule of thumb: the more ethically dubious the business, the more grandiose and sanctimonious its mission statement.

Facebook’s stated mission amounts to the salvation of humanity. In truth, the purpose of Facebook, a multinational corporation with headquarters in California, is to make money for its investors. Facebook is an advertising agency: it collects data and sells ads. Founded in 2004, it now has a market value of close to a trillion dollars.

More here.

More than two decades ago, when Elizabeth Turner was still a graduate student studying fossilized microbial reefs, she hammered out hundreds of lemon-sized rocks from weathered cliff faces in Canada’s Northwest Territories. She hauled her rocks back to the lab, sawed them into 30-micron-thick slivers—about half the diameter of human hair—and scrutinized her handiwork under a microscope. Only in about five of the translucent slices, she found a sea of slender squiggles that looked nothing like the microbes she was after. “It just didn’t fit. The microstructure was too complicated,” says Turner. “And it looked to me kind of familiar.”

More than two decades ago, when Elizabeth Turner was still a graduate student studying fossilized microbial reefs, she hammered out hundreds of lemon-sized rocks from weathered cliff faces in Canada’s Northwest Territories. She hauled her rocks back to the lab, sawed them into 30-micron-thick slivers—about half the diameter of human hair—and scrutinized her handiwork under a microscope. Only in about five of the translucent slices, she found a sea of slender squiggles that looked nothing like the microbes she was after. “It just didn’t fit. The microstructure was too complicated,” says Turner. “And it looked to me kind of familiar.” “T

“T I do not want to be soft-minded or irrational, pursue Dark Aged–ignorance, be any sort of woo-woo New Age mush head. I do not know my moon sign. I own a Tarot deck but do not know how to read the cards. I don’t know much about prayer, though I have aimed begging attention at thunderstorms to come, please come, break this heat, rip it open. I believe, in some ferocious kid place, that there’s a lot on this earth and beyond it that we don’t understand. No correlation? Maybe, instead, the more honest: we don’t know, we have not figured a way to measure, or to say. “Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot?” Bram Stoker asks. “It is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain.” Stephen Jay Gould had a name for this, when scientists interpret an absence of discernible change as no data, leaving significant signals from nature unseen, unreported, ignored.

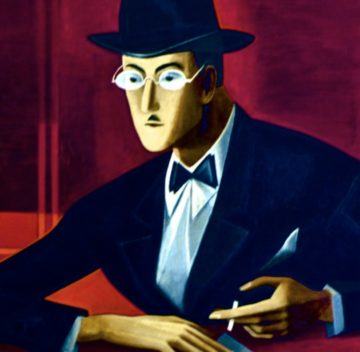

I do not want to be soft-minded or irrational, pursue Dark Aged–ignorance, be any sort of woo-woo New Age mush head. I do not know my moon sign. I own a Tarot deck but do not know how to read the cards. I don’t know much about prayer, though I have aimed begging attention at thunderstorms to come, please come, break this heat, rip it open. I believe, in some ferocious kid place, that there’s a lot on this earth and beyond it that we don’t understand. No correlation? Maybe, instead, the more honest: we don’t know, we have not figured a way to measure, or to say. “Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot?” Bram Stoker asks. “It is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain.” Stephen Jay Gould had a name for this, when scientists interpret an absence of discernible change as no data, leaving significant signals from nature unseen, unreported, ignored. When the ever elusive Fernando Pessoa died in Lisbon, in the fall of 1935, few people in Portugal realized what a great writer they had lost. None of them had any idea what the world was going to gain: one of the richest and strangest bodies of literature produced in the twentieth century. Although Pessoa lived to write and aspired, like poets from Ovid to Walt Whitman, to literary immortality, he kept his ambitions in the closet, along with the larger part of his literary universe. He had published only one book of his Portuguese poetry, Mensagem (Message), with forty-four poems, in 1934. It won a dubious prize from António Salazar’s autocratic regime, for poetic works denoting “a lofty sense of nationalist exaltation,” and dominated his literary résumé at the time of his death.

When the ever elusive Fernando Pessoa died in Lisbon, in the fall of 1935, few people in Portugal realized what a great writer they had lost. None of them had any idea what the world was going to gain: one of the richest and strangest bodies of literature produced in the twentieth century. Although Pessoa lived to write and aspired, like poets from Ovid to Walt Whitman, to literary immortality, he kept his ambitions in the closet, along with the larger part of his literary universe. He had published only one book of his Portuguese poetry, Mensagem (Message), with forty-four poems, in 1934. It won a dubious prize from António Salazar’s autocratic regime, for poetic works denoting “a lofty sense of nationalist exaltation,” and dominated his literary résumé at the time of his death.

‘The greatest living theoretical physicist’ – many commentators in the past few decades have described Steven Weinberg in such terms. When I rather cheekily asked him what he thought of that statement, he shot back: ‘It is quite ridiculous to rank scientists like that’, adding with a twinkle in his eye, ‘but it would be impolite to dispute the conclusion’. That reply was classic Weinberg: self-aware, intimidatingly direct but always ready to lighten the moment with humour.

‘The greatest living theoretical physicist’ – many commentators in the past few decades have described Steven Weinberg in such terms. When I rather cheekily asked him what he thought of that statement, he shot back: ‘It is quite ridiculous to rank scientists like that’, adding with a twinkle in his eye, ‘but it would be impolite to dispute the conclusion’. That reply was classic Weinberg: self-aware, intimidatingly direct but always ready to lighten the moment with humour. Elaine Scarry has been writing about the unique dangers and challenges of nuclear weapons in Boston Review for

Elaine Scarry has been writing about the unique dangers and challenges of nuclear weapons in Boston Review for  Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College.

Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. P

P Knowledge is so often assumed to be a good thing, particularly by philosophers, that we don’t think enough about when it makes sense to not want it. Perhaps you’re a parent and want to give your children space: you might be glad to not know all that they do when out of your sight. Perhaps you want to reconcile politically with a group that’s committed violence: it might be easier to move on if you deliberately spare yourself all the details of what they’ve done. There are, in fact, a variety of reasons why one might reasonably choose ignorance. One of the most obvious is to avoid needless pain.

Knowledge is so often assumed to be a good thing, particularly by philosophers, that we don’t think enough about when it makes sense to not want it. Perhaps you’re a parent and want to give your children space: you might be glad to not know all that they do when out of your sight. Perhaps you want to reconcile politically with a group that’s committed violence: it might be easier to move on if you deliberately spare yourself all the details of what they’ve done. There are, in fact, a variety of reasons why one might reasonably choose ignorance. One of the most obvious is to avoid needless pain. Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators

Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators  Herrington, a Dutch sustainability researcher and adviser to the Club of Rome, a Swiss thinktank, has

Herrington, a Dutch sustainability researcher and adviser to the Club of Rome, a Swiss thinktank, has  Julia Ann Moore (1847–1920), the “Sweet Singer of Michigan,” was one of the worst American poets of the nineteenth century, or perhaps of any century. Her ear for the clunky inverted phrase, or the just-miss rhyme, generated bad verse on patriotic themes and historical subjects, but what really inspired her was obituary poetry, a genre which thrived all through the nineteenth century, and which drew steadily on the talent—or lack of talent—of local amateur commemorative poets. And her specialty within a specialty was obituary poetry for those dying young: “Every time one of my darlings died, or any of the neighbor’s children were buried, I just wrote a poem on their death,” she told an interviewer from the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean in 1878. “That’s the way I got started.”

Julia Ann Moore (1847–1920), the “Sweet Singer of Michigan,” was one of the worst American poets of the nineteenth century, or perhaps of any century. Her ear for the clunky inverted phrase, or the just-miss rhyme, generated bad verse on patriotic themes and historical subjects, but what really inspired her was obituary poetry, a genre which thrived all through the nineteenth century, and which drew steadily on the talent—or lack of talent—of local amateur commemorative poets. And her specialty within a specialty was obituary poetry for those dying young: “Every time one of my darlings died, or any of the neighbor’s children were buried, I just wrote a poem on their death,” she told an interviewer from the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean in 1878. “That’s the way I got started.” It’s not hard to see what first drew Barnes and de Kooning to Soutine. His arresting portraits from the 1910s and ’20s, the first works on view, reveal both a wry distrust of himself and a sure confidence in his capacity to observe and render the inner lives of other people. In his laconic 1918 Self-Portrait, he’s clothed in a rumpled blue smock and stares straight ahead at the viewer; another portrait (evidently by Soutine) covers his right shoulder and fills the left side of the frame. Soutine is clearly channeling similar works by artists like Velázquez and Rembrandt, which he regularly studied in his frequent trips to the Louvre. Yet his own Self-Portrait, geometrically and chromatically centered on his puffy, blood-red lips, also evokes the grotesque—so called because it traditionally portrayed subjects best kept out of sight. After Barnes helped make him famous, Soutine began to appear at Parisian salons in elegant clothes (indeed, Polish writer and painter Józef Czapski calls attention to his “expensive felt hats and gleaming leather boots”), yet he remained something of an outsider.

It’s not hard to see what first drew Barnes and de Kooning to Soutine. His arresting portraits from the 1910s and ’20s, the first works on view, reveal both a wry distrust of himself and a sure confidence in his capacity to observe and render the inner lives of other people. In his laconic 1918 Self-Portrait, he’s clothed in a rumpled blue smock and stares straight ahead at the viewer; another portrait (evidently by Soutine) covers his right shoulder and fills the left side of the frame. Soutine is clearly channeling similar works by artists like Velázquez and Rembrandt, which he regularly studied in his frequent trips to the Louvre. Yet his own Self-Portrait, geometrically and chromatically centered on his puffy, blood-red lips, also evokes the grotesque—so called because it traditionally portrayed subjects best kept out of sight. After Barnes helped make him famous, Soutine began to appear at Parisian salons in elegant clothes (indeed, Polish writer and painter Józef Czapski calls attention to his “expensive felt hats and gleaming leather boots”), yet he remained something of an outsider.