Karthik Sankaran in Phenomenal World:

Donald Trump’s second term as President of the United States has not been very good for the dollar. The most recent blow to the currency came when the ratings agency Moody’s stripped the US of its AAA rating. When Standard & Poor’s downgraded the US in 2011, the dollar rallied and Treasury yields fell. This time around, however, the market reaction was different—an extension of the pattern established immediately following the announcement of sweeping global tariffs on April 2. In 2011, the Eurozone crisis was reaching a crescendo, making the dollar the safest haven in the international system. In 2025, the voluntary nature of the crisis has triggered considerably different market behavior. Contrary to the expectations of most economists (including administration officials charged with economic policy making), the so-called Liberation Day tariffs led to a sharp weakening of the dollar and momentary spiking of Treasury yields.

This in turn has fueled speculation of a broader flight from US assets, marked by a Munchian cover story in The Economist raising the shrieking specter of a dollar crisis. There has also been a mounting stream of stories and commentary that US policies were fueling a broader turn in sentiment against the currency—as suggested in this article about China looking at alternatives to US Treasuries, in invocations by Japan’s finance minister of the country’s US bond holdings as a possible negotiating card, and warnings that Asian countries could decide to reduce their exposure to US assets to the tune of $7.5 trillion.

The months since April 2 have clarified the multiple contradictory desires of the Trump administration vis-a-vis its position in the global economic hierarchy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Last year,

Last year, It was an anxious summer. The American elections loomed, the sitting president had just been unmasked as an egomaniacal member of the walking undead, and here on the continent, across the Atlantic, Europe was about to elect the most right-wing parliament in the history of the European Union. The streets were plastered with campaign posters. In Germany, high over the boulevards, a well-known comedian gripped an enormous toothbrush and flashed her pearly whites. “Wählen ist wie Zähneputzen. Machst du’s nicht, wird’s braun!” read the accompanying text, or, “Voting is like brushing your teeth: don’t do it, and things’ll go brown.” The joke is that the Nazis wore brownshirts. To “go brown” is to go Nazi. In essence, the suggested defense against such a future was “Brush your teeth for democracy.” Or worse: “We are the guardians of oral and political hygiene—be more like us.” You slobs. It wasn’t a message endorsed by the Democratic Party or its handpicked candidate, Kamala Harris, who spent the final weeks of her abbreviated but competent campaign warning against the dangers of fascism. But it could have been.

It was an anxious summer. The American elections loomed, the sitting president had just been unmasked as an egomaniacal member of the walking undead, and here on the continent, across the Atlantic, Europe was about to elect the most right-wing parliament in the history of the European Union. The streets were plastered with campaign posters. In Germany, high over the boulevards, a well-known comedian gripped an enormous toothbrush and flashed her pearly whites. “Wählen ist wie Zähneputzen. Machst du’s nicht, wird’s braun!” read the accompanying text, or, “Voting is like brushing your teeth: don’t do it, and things’ll go brown.” The joke is that the Nazis wore brownshirts. To “go brown” is to go Nazi. In essence, the suggested defense against such a future was “Brush your teeth for democracy.” Or worse: “We are the guardians of oral and political hygiene—be more like us.” You slobs. It wasn’t a message endorsed by the Democratic Party or its handpicked candidate, Kamala Harris, who spent the final weeks of her abbreviated but competent campaign warning against the dangers of fascism. But it could have been. “Everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who almost went out with Ted Bundy.”

“Everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who almost went out with Ted Bundy.” Consider this straightforward calculation: (10100) + 1 – (10100)

Consider this straightforward calculation: (10100) + 1 – (10100) In a city well-known for political theater, the show at Stone Nest, a performance venue in the heart of London’s West End, took the concept to a new level. For the last month, audiences have been reenacting the events of Jan. 6, 2021, when a pro-Trump mob stormed the U.S. Capitol in one of the most violent and divisive days of modern American democracy. But instead of sitting in stately silence, legs crammed into velvet chairs, attendees at “Fight for America” were active participants — singing, chanting, rolling dice, and maneuvering tiny figurines around a model of the Capitol.

In a city well-known for political theater, the show at Stone Nest, a performance venue in the heart of London’s West End, took the concept to a new level. For the last month, audiences have been reenacting the events of Jan. 6, 2021, when a pro-Trump mob stormed the U.S. Capitol in one of the most violent and divisive days of modern American democracy. But instead of sitting in stately silence, legs crammed into velvet chairs, attendees at “Fight for America” were active participants — singing, chanting, rolling dice, and maneuvering tiny figurines around a model of the Capitol. Friday is the 30th anniversary of the deadliest massacre in Europe since World War II, when Bosnian Serb forces under Gen. Ratko Mladic overran an area meant to be protected by the United Nations. Soon after, they proceeded to

Friday is the 30th anniversary of the deadliest massacre in Europe since World War II, when Bosnian Serb forces under Gen. Ratko Mladic overran an area meant to be protected by the United Nations. Soon after, they proceeded to  In a 1989 interview with the Detroit Free Press, director Charlotte Zwerin worried that her documentary Thelonious Monk Straight, No Chaser, then newly out in general release after premiering the year before, would be labeled a “jazz film.” Zwerin had grown up, in the 1930s and ’40s, in Detroit, where she had heard a lot of jazz and become a lifelong fan of the music, yet she wanted audiences to see simply that Monk was “an American composer of tremendous stature” who “wrote beautiful songs.” Watching Straight, No Chaser today, you see just what she meant—calling this music jazz (or even American) somehow dilutes the once-in-a-millennium originality of songs that can be heard with the same jolt of immediacy and surprise in all times, places, and genres.

In a 1989 interview with the Detroit Free Press, director Charlotte Zwerin worried that her documentary Thelonious Monk Straight, No Chaser, then newly out in general release after premiering the year before, would be labeled a “jazz film.” Zwerin had grown up, in the 1930s and ’40s, in Detroit, where she had heard a lot of jazz and become a lifelong fan of the music, yet she wanted audiences to see simply that Monk was “an American composer of tremendous stature” who “wrote beautiful songs.” Watching Straight, No Chaser today, you see just what she meant—calling this music jazz (or even American) somehow dilutes the once-in-a-millennium originality of songs that can be heard with the same jolt of immediacy and surprise in all times, places, and genres. 1910: Lahore

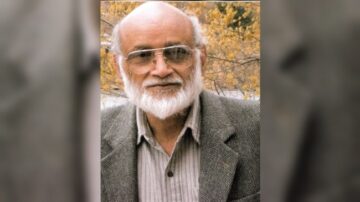

1910: Lahore Last night, a friend called to give me the sad news of Naim sahib’s passing. He had not been too well since suffering a stroke a couple of years ago but after returning from rehab his spirit was as indomitable as ever. He relished writing and wrote with zest; sparkling essays, columns and a weekly, later monthly, newsletter that he dispatched electronically to a large following. Naim sahib did not shy away from technology. He had a website on which he posted stuff that he liked. But the newsletter was his commentary on various subjects related to literature, including world politics that impacted literature. He wrote what was on his mind without mincing the truth. It was a privilege to be on his mailing list.

Last night, a friend called to give me the sad news of Naim sahib’s passing. He had not been too well since suffering a stroke a couple of years ago but after returning from rehab his spirit was as indomitable as ever. He relished writing and wrote with zest; sparkling essays, columns and a weekly, later monthly, newsletter that he dispatched electronically to a large following. Naim sahib did not shy away from technology. He had a website on which he posted stuff that he liked. But the newsletter was his commentary on various subjects related to literature, including world politics that impacted literature. He wrote what was on his mind without mincing the truth. It was a privilege to be on his mailing list. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some people took up baking, others decided to get a dog; I chose to grow and observe slime mould. The study in my partner’s flat in Edinburgh became home to two cultures of Physarum polycephalum, an acellular slime mould sometimes more casually referred to as ‘the blob’.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some people took up baking, others decided to get a dog; I chose to grow and observe slime mould. The study in my partner’s flat in Edinburgh became home to two cultures of Physarum polycephalum, an acellular slime mould sometimes more casually referred to as ‘the blob’. When you accept that other people have secrets, and they will always have secrets, you are preparing yourself for a much more predictable, much more successful future. Because once you accept that reality, you can start applying behaviors, practices into your personal life, into your business life that make it so that you gain more secrets than you share. And gaining secrets in an economy of secrets is the same thing as gaining wealth or gaining power or gaining leverage. You can either live in a world that is not true and believe that people are honest, or you can live in a world that is factual and objective and recognize that all people are keeping secrets from you.

When you accept that other people have secrets, and they will always have secrets, you are preparing yourself for a much more predictable, much more successful future. Because once you accept that reality, you can start applying behaviors, practices into your personal life, into your business life that make it so that you gain more secrets than you share. And gaining secrets in an economy of secrets is the same thing as gaining wealth or gaining power or gaining leverage. You can either live in a world that is not true and believe that people are honest, or you can live in a world that is factual and objective and recognize that all people are keeping secrets from you. The Thinker just discovered, with a mix of awe and quiet dread, that ChatGPT—a machine—could write his latest policy memo better and faster than he could.

The Thinker just discovered, with a mix of awe and quiet dread, that ChatGPT—a machine—could write his latest policy memo better and faster than he could.