Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Wednesday Poem

Gaza the Immortal City

I walk through the city of the immortals,

haiya alas salah haiya alal falah,

They blossom like cherries, and bloom like black iris.

Gary Shteyngart on Channeling a Precocious Child Narrator

Gary Shteyngart and Jane Ciabattari at Lit Hub:

Vera, the buzzy, brilliant and preternaturally observant ten-year-old central to Gary Shteyngart’s sardonic and profoundly relevant new novel, brings a fresh, necessary perspective to our evolving dystopian universe. Her anxieties as the Russian Jewish-Korean daughter of immigrants surviving in a fraught domestic atmosphere made me pull Shteyngart’s panic-loaded 2014 memoir Little Failure from my bookcase. Yes, there are echoes of the “tightly wound” young Gary, who begins his first unpublished novel in English at ten, in Vera, or Faith. But Vera, in her heart, knows she’s not a failure. And the life of immigrants in 2025 is infinitely more complicated than a decade ago.

Ironically, Vera’s existence may result from a sushi lunch that went sideways. Indeed, Shteyngart wrote Vera, or Faith, in a whirlwind. His editor, David Ebershoff, mentioned that he delivered the novel 51 days after a sushi lunch at which Ebershoff suggested the multigenerational saga Shteyngart had been working on wasn’t working.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Love Letter to Vermeer

Jerry Saltz at New York Magazine:

Does anyone write love letters anymore? We send emails. Or worse, texts, emoji. Fast, short, disposable. Once, love letters were slow to make and slower to arrive. They were keepsakes, confessions, feelings made physical. They had form. They were a genre unto themselves: often florid, achingly raw, very private. I’ve written them. Maybe you have, too. Now they’ve all but vanished — and with them, a particular architecture of emotion.

Does anyone write love letters anymore? We send emails. Or worse, texts, emoji. Fast, short, disposable. Once, love letters were slow to make and slower to arrive. They were keepsakes, confessions, feelings made physical. They had form. They were a genre unto themselves: often florid, achingly raw, very private. I’ve written them. Maybe you have, too. Now they’ve all but vanished — and with them, a particular architecture of emotion.

The Frick’s luminous new show, “Vermeer’s Love Letters,” captures the essence of that lost world. Curator Aimee Ng says it’s “a very Frick show,” by which she means there are no gimmicks or didactics, just the art. Three paintings, one room, no men. Each painting features two women — a lady and her servant — as well as a letter either being written or accepted. Only one painting, The Love Letter (on loan from the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands), is explicitly identified as a billet-doux, but all three are suggestive of interior dramas; secret vulnerabilities and joys; two selves reaching toward one another.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, July 8, 2025

Why Illiberalism Explains Changes in Today’s Social Order

Marlene Laruelle in the Politics and Rights Review:

Scholarship on populism has dominated the last two decades but is now retreating in the face of a new concept that seems better equipped to capture the current transformations in our society: that of illiberalism. Illiberalism emerged first in the transition studies field (one may recall Fareed Zakaria’s famous “Illiberal Democracy” article in Foreign Affairs from 1997), as well as in the Asian Studies field, with studies on the rise of East Asian values embodied by Singapore.

Scholarship on populism has dominated the last two decades but is now retreating in the face of a new concept that seems better equipped to capture the current transformations in our society: that of illiberalism. Illiberalism emerged first in the transition studies field (one may recall Fareed Zakaria’s famous “Illiberal Democracy” article in Foreign Affairs from 1997), as well as in the Asian Studies field, with studies on the rise of East Asian values embodied by Singapore.

It then grew to encompass the Central European democratic backlash, encapsulated by Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, before eventually reaching the study of the well-established Western democracies and their liberal erosion in the 2010s. The move from an adjective, “illiberal,” to a noun, “illiberalism,” reflects both the intellectual thickening of the protest mood against the current social order and, simultaneously, a better conceptualization of it in the scholarship.

The concept of illiberalism indeed provides a far better descriptor than does populism, as the former asserts that we have moved well beyond the stage of a mere protest mood: parts of our constituencies are now ready to experiment with different social orders.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Book Review: “Is A River Alive?”

Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

Nature writer Robert Macfarlane will need little introduction, having authored a string of successful books on people, landscape, and language. I was impressed by his 2019 book Underland, so when Is a River Alive? was announced, I decided to spoil myself and purchase the signed Indie Exclusive edition. Billed as his most political book to date, Is a River Alive? is a hydrological odyssey into three river systems that sees Macfarlane wrestle with the titular question and examine its relevance to the nascent Rights of Nature movement.

Nature writer Robert Macfarlane will need little introduction, having authored a string of successful books on people, landscape, and language. I was impressed by his 2019 book Underland, so when Is a River Alive? was announced, I decided to spoil myself and purchase the signed Indie Exclusive edition. Billed as his most political book to date, Is a River Alive? is a hydrological odyssey into three river systems that sees Macfarlane wrestle with the titular question and examine its relevance to the nascent Rights of Nature movement.

At the heart of this book are three long, 70–100-page parts that detail visits to three river systems in Ecuador, India, and Canada. They are separated by short palate cleansers, describing brief visits to local springs close to his home in Cambridge. In the back, you will find a surprisingly thorough 10-page glossary, notes, a select bibliography, a combined acknowledgements and aftermaths section detailing developments up to publication, and an index.

This dry enumeration aside, it is the quality of the writing that we are all here for, and Macfarlane is on fine form as he immerses you in the landscapes he visits.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Deutsch: “There is only one interpretation of quantum mechanics”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The End of America’s Exorbitant Privilege

Desmond Lachman at Project Syndicate:

When he was France’s finance minister in the 1960s, former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously complained about the “exorbitant privilege” that the dollar’s position as the world’s leading reserve currency conferred on the United States. This meant, essentially, that the US could borrow at low interest rates, run persistently large trade deficits, and print money to finance its budget deficits. He never could have imagined that the US would end up letting these advantages slip through its fingers.

When he was France’s finance minister in the 1960s, former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously complained about the “exorbitant privilege” that the dollar’s position as the world’s leading reserve currency conferred on the United States. This meant, essentially, that the US could borrow at low interest rates, run persistently large trade deficits, and print money to finance its budget deficits. He never could have imagined that the US would end up letting these advantages slip through its fingers.

Since returning to the White House in January, US President Donald Trump has been systematically destroying faith in the dollar in both global financial markets and among governments and central banks. For starters, Trump has put America’s public finances on an even more unsustainable path than they were on before he took office.

When Trump began his second term, the US budget deficit had already widened to 6.2% of GDP, with nearly full employment, while the public-debt-to-GDP ratio had risen to around 100%. But things are about to get much worse.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Peter Thiel And The Antichrist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

How Things Happen

Rain comes when it will. It doesn’t care for us.

It’s hitchhiking its way to the sea on a cloud.

The sun is interested in its own fires. If light

comes, so be it. Bees feel an itch on their legs

only nectar can sooth. So many gifts from indifferent

givers. We walk through the world and smile,

remembering an old love, and Ramona, passing by,

thinks That man thinks I’m pretty, and walks in a way

that makes her more beautiful – and Henry,

walking down the street notices, makes a pass,

and they end up having a good marriage.

by Nils Peterson

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Who Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill Really Helps

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Moss Medicines: The Next Revolution in Biotech?

Rebecca Roberts in The Scientist:

Moss is an often-overlooked, ancient plant that is far from insignificant. Among the first to colonize land, mosses greened the planet and transformed Earth’s climate, providing an oxygen-rich atmosphere that allowed animals to evolve.1 These hardy pioneers can even filter and clean the polluted air of cities.2,3

Moss is an often-overlooked, ancient plant that is far from insignificant. Among the first to colonize land, mosses greened the planet and transformed Earth’s climate, providing an oxygen-rich atmosphere that allowed animals to evolve.1 These hardy pioneers can even filter and clean the polluted air of cities.2,3

Where others see a natural air purifier, Ralf Reski, a plant biotechnologist at the University of Freiburg, saw untapped potential in moss. In addition to the range of valuable compounds they produce naturally, Reski believed it made an ideal culture system to grow recombinant human proteins at scale. Reski first worked on moss as an undergraduate, studying their genetics. He immediately fell in love with the tiny plants, so much so that he asked his supervisor if he could continue working on them for a PhD project. From those early days, his peers quickly dismissed the notion, pointing out that mosses didn’t have to do anything with biotechnology. “You will never become a professor in Germany unless you work with real plants. Nobody is interested in mosses,” Reski recalled the caution from senior professors.

But he persisted.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

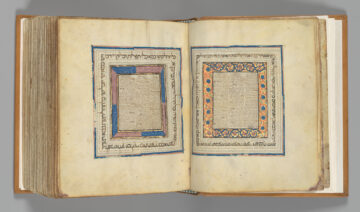

Jewish And Christian Thinking

Olga Litvak at The Hedgehog Review:

From the Christian perspective, the hyphen is a sign of Jewish translatability; but the same sign, read, we might say, from right to left, also points to a more confrontational reality, that of Jewish resistance to being translated (elevated) into a (higher) Christian register. The Jewish insistence on reading “the Bible” in Hebrew every week, in synagogue, to congregations whose first language was (and is) probably not the language of the patriarchs but the language of their non-Jewish neighbors, is a performance of otherness. We can see what is at stake in this attachment to the original when we appreciate the difference between reading Hebrew texts in Greek—from right to left—and reading the Bible as a Greek text, from left to right. From the perspective of the former, the Alexandrian translation of ’almah as parthenos provides a Jewish textual source for the Christian myth of the virgin birth. From the perspective of the latter, the same translation turns the Tanakh (a set of texts) into the Bible (a book).

From the Christian perspective, the hyphen is a sign of Jewish translatability; but the same sign, read, we might say, from right to left, also points to a more confrontational reality, that of Jewish resistance to being translated (elevated) into a (higher) Christian register. The Jewish insistence on reading “the Bible” in Hebrew every week, in synagogue, to congregations whose first language was (and is) probably not the language of the patriarchs but the language of their non-Jewish neighbors, is a performance of otherness. We can see what is at stake in this attachment to the original when we appreciate the difference between reading Hebrew texts in Greek—from right to left—and reading the Bible as a Greek text, from left to right. From the perspective of the former, the Alexandrian translation of ’almah as parthenos provides a Jewish textual source for the Christian myth of the virgin birth. From the perspective of the latter, the same translation turns the Tanakh (a set of texts) into the Bible (a book).

Christian readers who read ’almah as parthenos locate in this translation a proof text for the argument that the Bible constitutes a single narrative with a sad Jewish beginning and a happy Christian ending, a form imitated by countless European and American novels and turned into a near-universal cultural staple by Hollywood; Jewish film moguls propagated it among the gentiles no less zealously than the early Christians who were, of course, all Jews.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Nettie Jones’s Classic Novel

Harmony Holiday at Bookforum:

Fish Tales, released this spring in a new edition and still pioneering decades after its first run, slices into the flesh of the novel of ideas with events and characters who loom so large they leave no room for indulgent ideological abstractions; they are busy being sluts and disasters at the exact moment you might expect more recognizable or coherent archetypes to buckle begrudgingly into the routines of adult life and surrender to them for the sake of reputation, supposed stability, or ego. Transgressive to the point of exhilarating, Nettie Jones’s prose avoids etiquette or the impulse to virtue signal: this perspective of a girl molested by her schoolteacher, whose life subsequently becomes so centered on male approval she pretends she’s sexually liberated instead of a victim of circumstance and tragic hero, makes no excuses for the procession of orgies and nervous breakdowns that becomes the novel’s plot. Hedonism grows banal as we’re trapped in bed with the protagonist, her demons, and the doom disguised as suitors, flatterers, and one husband, Woody, who after a brief attempt at real union becomes Lewis’s overseer and benefactor, allowing her to hire prostitutes or travel to New York to meet with lovers while he takes his own new girlfriend. All the while he sustains Lewis, “his favorite woman,” with an allowance and a roof over her head.

Fish Tales, released this spring in a new edition and still pioneering decades after its first run, slices into the flesh of the novel of ideas with events and characters who loom so large they leave no room for indulgent ideological abstractions; they are busy being sluts and disasters at the exact moment you might expect more recognizable or coherent archetypes to buckle begrudgingly into the routines of adult life and surrender to them for the sake of reputation, supposed stability, or ego. Transgressive to the point of exhilarating, Nettie Jones’s prose avoids etiquette or the impulse to virtue signal: this perspective of a girl molested by her schoolteacher, whose life subsequently becomes so centered on male approval she pretends she’s sexually liberated instead of a victim of circumstance and tragic hero, makes no excuses for the procession of orgies and nervous breakdowns that becomes the novel’s plot. Hedonism grows banal as we’re trapped in bed with the protagonist, her demons, and the doom disguised as suitors, flatterers, and one husband, Woody, who after a brief attempt at real union becomes Lewis’s overseer and benefactor, allowing her to hire prostitutes or travel to New York to meet with lovers while he takes his own new girlfriend. All the while he sustains Lewis, “his favorite woman,” with an allowance and a roof over her head.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, July 7, 2025

When is a chair not a chair?

Brooks Riley in Art at First Sight:

In the recent K-Drama Our Unwritten Seoul, a simple wooden chair emerges as the iconic stand-in (or sit-in) for a young farmer’s late grandfather, whose favorite chair it had once been. Broken and mended multiple times, patched together with tape, glue, and hastily hammered braces, the chair, on its last legs, gets tossed out by an over-zealous new employee. The young farmer is devastated.

In the recent K-Drama Our Unwritten Seoul, a simple wooden chair emerges as the iconic stand-in (or sit-in) for a young farmer’s late grandfather, whose favorite chair it had once been. Broken and mended multiple times, patched together with tape, glue, and hastily hammered braces, the chair, on its last legs, gets tossed out by an over-zealous new employee. The young farmer is devastated.

Beyond the obvious metaphor hovering over this minor incident (Age and infirmity are not to be mistaken for worthlessness), the tale rings a bell. How many of us remember a favorite chair, where daydreams were forged, books were read, naps were taken, and the universe doom-scrolled on an app? Or an empty chair at the table as someone’s ghostly absence?

Chairs are fundamental accessories in our lives–dependable, discreet, dotted about our personal periphery like silent sentries—there but not there, part of the family, but also not.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Researchers Uncover Hidden Ingredients Behind AI Creativity

Webb Wright in Quanta:

To generate images, diffusion models use a process known as denoising. They convert an image into digital noise (an incoherent collection of pixels), then reassemble it. It’s like repeatedly putting a painting through a shredder until all you have left is a pile of fine dust, then patching the pieces back together. For years, researchers have wondered: If the models are just reassembling, then how does novelty come into the picture? It’s like reassembling your shredded painting into a completely new work of art.

To generate images, diffusion models use a process known as denoising. They convert an image into digital noise (an incoherent collection of pixels), then reassemble it. It’s like repeatedly putting a painting through a shredder until all you have left is a pile of fine dust, then patching the pieces back together. For years, researchers have wondered: If the models are just reassembling, then how does novelty come into the picture? It’s like reassembling your shredded painting into a completely new work of art.

Now two physicists have made a startling claim: It’s the technical imperfections in the denoising process itself that leads to the creativity of diffusion models. In a paper(opens a new tab) that will be presented at the International Conference on Machine Learning 2025, the duo developed a mathematical model of trained diffusion models to show that their so-called creativity is in fact a deterministic process — a direct, inevitable consequence of their architecture.

By illuminating the black box of diffusion models, the new research could have big implications for future AI research — and perhaps even for our understanding of human creativity.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Azra Raza’s SFU Commencement Speech

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dancing with Putin: how Austria’s former foreign minister found a new home in Russia

Amanda Coakley in The Guardian:

The trouble started with a dead cat. For years, the people of Seibersdorf had lived amicably alongside their most famous resident, more or less. True, there had been an incident when a neighbour complained about the smell of her horses. And yes, there had been rumblings about her lack of community spirit, that she was great at giving orders for neighbourhood events but never pitched in to fry a schnitzel or hang bunting. But for the most part, they got along.

The trouble started with a dead cat. For years, the people of Seibersdorf had lived amicably alongside their most famous resident, more or less. True, there had been an incident when a neighbour complained about the smell of her horses. And yes, there had been rumblings about her lack of community spirit, that she was great at giving orders for neighbourhood events but never pitched in to fry a schnitzel or hang bunting. But for the most part, they got along.

Karin Kneissl was a blow-in from Vienna, an hour north. She had lived in Seibersdorf for more than two decades, moving into a rickety old apartment before buying a house near the central square. She had arrived as a junior diplomat, then became a freelance journalist and later began lecturing on international relations at some of Austria’s most prestigious institutions. For a brief period, she also sat on the town’s parish council.

Then, in 2017, Kneissl became Austria’s foreign minister. It was a sudden appointment and it surprised everyone in town. But when the residents stopped to think about it, it made a certain amount of sense. Kneissl was a true eccentric, the kind of person who was always doing and saying unexpected things. You never quite knew where she would go next, so why not the Austrian foreign ministry?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dogs and their people: Companions in cancer research

Bob Holmes in Knowable Magazine:

After a train carrying chemicals derailed and caught fire in East Palestine, Ohio, in 2023, residents were exposed to carcinogens such as vinyl chloride, acrolein and dioxin. Since tumors are typically slow to develop, it could take decades to know what that did to the locals’ cancer risk, but there may be a quicker route to an answer: The residents’ dogs were also exposed, and dogs develop cancer more quickly.

After a train carrying chemicals derailed and caught fire in East Palestine, Ohio, in 2023, residents were exposed to carcinogens such as vinyl chloride, acrolein and dioxin. Since tumors are typically slow to develop, it could take decades to know what that did to the locals’ cancer risk, but there may be a quicker route to an answer: The residents’ dogs were also exposed, and dogs develop cancer more quickly.

Studying dogs and their cancers turns out to be an excellent way to learn more about cancer in people. And it’s not just that dogs and owners share exposures to many of the same environmental carcinogens. Researchers are also learning that cancers develop along remarkably similar pathways in the two species.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

New Google AI Will Work Out What 98% of Our DNA Actually Does for the Body

Edd Gent in Singularity Hub:

Vast swathes of the human genome remain a mystery to science. A new AI from Google DeepMind is helping researchers understand how these stretches of DNA impact the activity of other genes. While the Human Genome Project produced a complete map of our DNA, we still know surprisingly little about what most of it does. Roughly 2 percent of the human genome encodes specific proteins, but the purpose of the other 98 percent is much less clear.

Vast swathes of the human genome remain a mystery to science. A new AI from Google DeepMind is helping researchers understand how these stretches of DNA impact the activity of other genes. While the Human Genome Project produced a complete map of our DNA, we still know surprisingly little about what most of it does. Roughly 2 percent of the human genome encodes specific proteins, but the purpose of the other 98 percent is much less clear.

Historically, scientists called this part of the genome “junk DNA.” But there’s growing recognition these so-called “non-coding” regions play a critical role in regulating the expression of genes elsewhere in the genome. Teasing out these interactions is a complicated business. But now a new Google DeepMind model called AlphaGenome can take long stretches of DNA and make predictions about how different genetic variants will affect gene expression, as well as a host of other important properties. “We have, for the first time, created a single model that unifies many different challenges that come with understanding the genome,” Pushmeet Kohli, a vice president for research at DeepMind, told MIT Technology Review.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.