Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

This new surge brings a jarring sense of déjà vu. America has fallen prey to many of the same self-destructive but alluring instincts that I identified last year. It went all in on one countermeasure—vaccines—and traded it off against masks and other protective measures. It succumbed to magical thinking by acting as if a variant that had ravaged India would spare a country where half the population still hadn’t been vaccinated. It stumbled into the normality trap, craving a return to the carefree days of 2019; in May, after the CDC ended indoor masking for vaccinated people, President Joe Biden gave a speech that felt like a declaration of victory. Three months later, cases and hospitalizations are rising, indoor masking is back, and schools and universities are opening uneasily—again. “It’s the eighth month of 2021, and I can’t believe we’re still having these conversations,” Jessica Malaty Rivera, an epidemiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, told me.

This new surge brings a jarring sense of déjà vu. America has fallen prey to many of the same self-destructive but alluring instincts that I identified last year. It went all in on one countermeasure—vaccines—and traded it off against masks and other protective measures. It succumbed to magical thinking by acting as if a variant that had ravaged India would spare a country where half the population still hadn’t been vaccinated. It stumbled into the normality trap, craving a return to the carefree days of 2019; in May, after the CDC ended indoor masking for vaccinated people, President Joe Biden gave a speech that felt like a declaration of victory. Three months later, cases and hospitalizations are rising, indoor masking is back, and schools and universities are opening uneasily—again. “It’s the eighth month of 2021, and I can’t believe we’re still having these conversations,” Jessica Malaty Rivera, an epidemiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, told me.

But something is different now—the virus. “The models in late spring were pretty consistent that we were going to have a ‘normal’ summer,” Samuel Scarpino of the Rockefeller Foundation, who studies infectious-disease dynamics, told me. “Obviously, that’s not where we are.”

More here.

The magnitude of the United States’ failure in Afghanistan is breathtaking. It is not a failure of Democrats or Republicans, but an abiding failure of American political culture, reflected in US policymakers’ lack of interest in understanding different societies. And it is all too typical.

The magnitude of the United States’ failure in Afghanistan is breathtaking. It is not a failure of Democrats or Republicans, but an abiding failure of American political culture, reflected in US policymakers’ lack of interest in understanding different societies. And it is all too typical. The two dozen Kalamazoo County Republicans are rapt. They sit shoulder to shoulder in foldout chairs as the guest speaker at their party meeting, who bills himself as an IT expert from the West Coast, details allegations of fraud he claims occurred in Michigan during the 2020 presidential election. No such fraud occurred, according to

The two dozen Kalamazoo County Republicans are rapt. They sit shoulder to shoulder in foldout chairs as the guest speaker at their party meeting, who bills himself as an IT expert from the West Coast, details allegations of fraud he claims occurred in Michigan during the 2020 presidential election. No such fraud occurred, according to  I met the most rational person I know during my freshman year of college. Greg (not his real name) had a tech-support job in the same computer lab where I worked, and we became friends. I planned to be a creative-writing major; Greg told me that he was deciding between physics and economics. He’d choose physics if he was smart enough, and economics if he wasn’t—he thought he’d know within a few months, based on his grades. He chose economics.

I met the most rational person I know during my freshman year of college. Greg (not his real name) had a tech-support job in the same computer lab where I worked, and we became friends. I planned to be a creative-writing major; Greg told me that he was deciding between physics and economics. He’d choose physics if he was smart enough, and economics if he wasn’t—he thought he’d know within a few months, based on his grades. He chose economics. Like many tales of compulsion, Campbell’s Hero brings dangers to those who put their faith in it. The first is a serious misunderstanding of how myth works. Myths and traditional stories function in specific environments for reasons bounded by time and place. Common traits are interesting, but the differences — what we might call variations or multiforms — cannot be ignored.

Like many tales of compulsion, Campbell’s Hero brings dangers to those who put their faith in it. The first is a serious misunderstanding of how myth works. Myths and traditional stories function in specific environments for reasons bounded by time and place. Common traits are interesting, but the differences — what we might call variations or multiforms — cannot be ignored. N

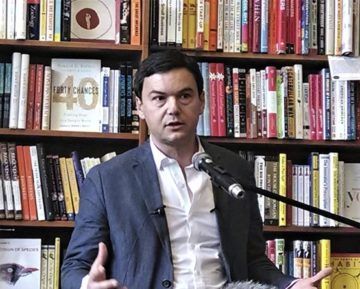

N The Paris-based economist Thomas Piketty gained worldwide fame in 2014 for his Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which analyzed rising inequality in the modern world and offered new ways to understand data on income, wealth accumulation, and the changing value of labor. In 2020 he followed with another similarly massive, similarly impressive tome, Capital and Ideology, which looks at the belief systems that underly that data. In it he asks the kind of question economic historians tend to shy away from: Where does inequality come from and why do societies naturalize and put up with it? Put another way: Why aren’t we all screaming?

The Paris-based economist Thomas Piketty gained worldwide fame in 2014 for his Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which analyzed rising inequality in the modern world and offered new ways to understand data on income, wealth accumulation, and the changing value of labor. In 2020 he followed with another similarly massive, similarly impressive tome, Capital and Ideology, which looks at the belief systems that underly that data. In it he asks the kind of question economic historians tend to shy away from: Where does inequality come from and why do societies naturalize and put up with it? Put another way: Why aren’t we all screaming? Over the past millennia, humans have developed a remarkable notion of counting. Originally applied to a handful of objects, it was easily extended to vastly different orders of magnitude. Soon a mathematical framework emerged that could be used to describe huge quantities, such as the distance between galaxies or the number of elementary particles in the universe, as well as barely conceivable distances in the microcosm, between atoms or quarks.

Over the past millennia, humans have developed a remarkable notion of counting. Originally applied to a handful of objects, it was easily extended to vastly different orders of magnitude. Soon a mathematical framework emerged that could be used to describe huge quantities, such as the distance between galaxies or the number of elementary particles in the universe, as well as barely conceivable distances in the microcosm, between atoms or quarks. In Afghanistan, kinship and tribal connections often take precedence over formal political loyalties, or at least create neutral spaces where people from opposite sides can meet and talk. Over the years, I have spoken with tribal leaders from the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region who have regularly presided over meetings of tribal notables, including commanders on opposite sides.

In Afghanistan, kinship and tribal connections often take precedence over formal political loyalties, or at least create neutral spaces where people from opposite sides can meet and talk. Over the years, I have spoken with tribal leaders from the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region who have regularly presided over meetings of tribal notables, including commanders on opposite sides. If Siri responded to your questions with QAnon conspiracy theories, would you want her answers to be legally protected? Would your verdict change if we labeled Siri’s answers either “computer generated” or “meaningful language?” Or as legal scholars Ronald Collins and David Skover ask in their recent monograph, Robotica: Speech Rights and Artificial Intelligence (2018), should the “constitutional conception of speech” be extended “to the semi-autonomous creation and delivery of robotic speech?”

If Siri responded to your questions with QAnon conspiracy theories, would you want her answers to be legally protected? Would your verdict change if we labeled Siri’s answers either “computer generated” or “meaningful language?” Or as legal scholars Ronald Collins and David Skover ask in their recent monograph, Robotica: Speech Rights and Artificial Intelligence (2018), should the “constitutional conception of speech” be extended “to the semi-autonomous creation and delivery of robotic speech?” Wilkes, who is thirty-one, grew up in Connecticut, and Gendel, who is thirty-five, grew up in central California. Both were drawn to Los Angeles by way of the jazz program at the University of Southern California. They turned out to have mixed feelings about studying jazz in a university setting. And maybe they had mixed feelings, too, about being tied to a tradition that arouses as much strong feeling—and, worse, as much weak feeling—as jazz does. As a boy, Wilkes was obsessed with the Grateful Dead and Phish, which gave him a love of improvisation. By the time he applied to U.S.C., he was a proficient electric-bass player, and, although he knew that the jazz program typically accepted only upright-bass players, he figured that the jazz bureaucracy might make an exception for him. It did not, and so he studied R. & B. and funk instead, working with a string of legendary musicians, including Patrice Rushen, an esteemed composer and keyboardist, and Leon (Ndugu) Chancler, a drum virtuoso. This was not a sad story: it turned out that Wilkes loved session playing, which demands precision and adaptability, and he had no complaints about his college experience. But, as Wilkes talked in the studio, Gendel grew outraged on his behalf—he couldn’t abide the idea that a jazz department would reject an eager student just because he played the wrong instrument. “It’s the most anti-jazz, anti-open-minded mentality I can imagine,” he said, becoming more animated than he’d been all afternoon. “This is why I’m against it all. It’s just stupid!”

Wilkes, who is thirty-one, grew up in Connecticut, and Gendel, who is thirty-five, grew up in central California. Both were drawn to Los Angeles by way of the jazz program at the University of Southern California. They turned out to have mixed feelings about studying jazz in a university setting. And maybe they had mixed feelings, too, about being tied to a tradition that arouses as much strong feeling—and, worse, as much weak feeling—as jazz does. As a boy, Wilkes was obsessed with the Grateful Dead and Phish, which gave him a love of improvisation. By the time he applied to U.S.C., he was a proficient electric-bass player, and, although he knew that the jazz program typically accepted only upright-bass players, he figured that the jazz bureaucracy might make an exception for him. It did not, and so he studied R. & B. and funk instead, working with a string of legendary musicians, including Patrice Rushen, an esteemed composer and keyboardist, and Leon (Ndugu) Chancler, a drum virtuoso. This was not a sad story: it turned out that Wilkes loved session playing, which demands precision and adaptability, and he had no complaints about his college experience. But, as Wilkes talked in the studio, Gendel grew outraged on his behalf—he couldn’t abide the idea that a jazz department would reject an eager student just because he played the wrong instrument. “It’s the most anti-jazz, anti-open-minded mentality I can imagine,” he said, becoming more animated than he’d been all afternoon. “This is why I’m against it all. It’s just stupid!” I

I When Yas Crawford started feeling the effects of her chronic illness, she says she felt as if her body and mind were at war. “When you’re ill for a long time, your body takes over,” she says. “Your brain wants to do one thing, and your body does something else.”

When Yas Crawford started feeling the effects of her chronic illness, she says she felt as if her body and mind were at war. “When you’re ill for a long time, your body takes over,” she says. “Your brain wants to do one thing, and your body does something else.” My beloved if

My beloved if