Chris Lehmann in The New Republic:

Chris Lehmann in The New Republic:

Of all the recently departed thinkers who might have helped us puzzle through the dismal political, intellectual, and socioeconomic prospects of the Trump era, perhaps none looms as large as Richard Rorty. Shortly after the 2016 election, the great pragmatist philosopher, who died in 2007, won fresh viral renown thanks to a widely quoted passage from his 1998 book Achieving Our Country, which appeared to prophesy the conditions of Donald Trump’s shocking ascension to the presidency.

Working-class Americans, he wrote, “will sooner or later realize that their government is not even trying to prevent wages from sinking or jobs from being exported.” Nor will suburban white-collar workers, struggling against their own brand of office-park precarity, “let themselves be taxed to provide social benefits for somebody else.” So in short order, Rorty argued, “something will crack. The nonsuburban electorate will decide that the system has failed them and start looking for a strongman to vote for—someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodern professors will no longer be calling the shots.”

Never mind that Trump actually won a majority of the white suburban electorate’s support as well; the general outlines of Rorty’s forecast helped explain the pseudopopulist, protectionist, and white nationalist takeover of the Republican Party—a realignment that has outlasted Trump’s term in office.

More here.

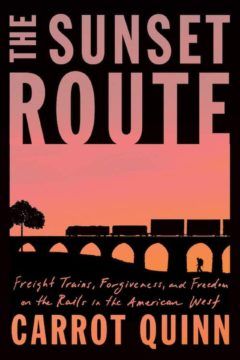

THE UNITED STATES has forgotten the hobo. We recognize the problem of homelessness, but the rootless rambler who steals rides on freight trains seems a relic of a long gone past. Even the word itself, hobo, is outdated. The same goes for the word tramp, which, if used at all tends to be for slut-shaming purposes. The term bum remains, but it, too, is derogatory, perhaps only acceptable as a verb, as in, “Can I bum a smoke?”

THE UNITED STATES has forgotten the hobo. We recognize the problem of homelessness, but the rootless rambler who steals rides on freight trains seems a relic of a long gone past. Even the word itself, hobo, is outdated. The same goes for the word tramp, which, if used at all tends to be for slut-shaming purposes. The term bum remains, but it, too, is derogatory, perhaps only acceptable as a verb, as in, “Can I bum a smoke?” Emilie Bickerton in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Emilie Bickerton in the NLR’s Sidecar: Kim Stanley Robinson in the FT:

Kim Stanley Robinson in the FT: T

T When you go on a first date, do you struggle to make conversation? Read Morris Bishop’s

When you go on a first date, do you struggle to make conversation? Read Morris Bishop’s  There is a parallel between Timothy Brennan’s biography of Edward Said and the latter’s most famous book. Like Orientalism in 1978, Places of Mind appears at a time when colonialism and race have once again become subjects of public debate in North America and Western Europe. Reviewers have linked the reception of Said’s book and the politics it enunciated to that facing the supporters of movements like Black Lives Matter or Rhodes Must Fall. And it was to find out how we might understand such a trajectory that I was eager to read the biography. Said was one of the earliest non-European immigrants to achieve fame in the American academy, and I wanted to know how he managed to spark the first new debate on imperialism there since its formal dissolution.

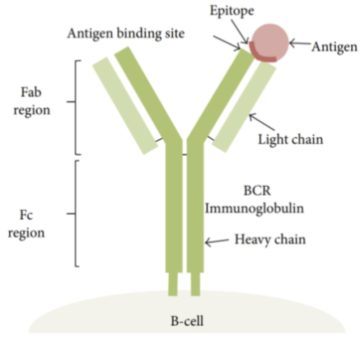

There is a parallel between Timothy Brennan’s biography of Edward Said and the latter’s most famous book. Like Orientalism in 1978, Places of Mind appears at a time when colonialism and race have once again become subjects of public debate in North America and Western Europe. Reviewers have linked the reception of Said’s book and the politics it enunciated to that facing the supporters of movements like Black Lives Matter or Rhodes Must Fall. And it was to find out how we might understand such a trajectory that I was eager to read the biography. Said was one of the earliest non-European immigrants to achieve fame in the American academy, and I wanted to know how he managed to spark the first new debate on imperialism there since its formal dissolution. As many countries are going through another wave of infections, including some where the vast majority of the population has been vaccinated, many are starting to despair that we’ll ever see the end of the pandemic. In this post, I will argue that, on the contrary, not only is the pandemic already on its way out, but the virus will be relatively harmless after it has become endemic. This is going to happen not because the SARS-CoV-2 will become intrinsically less dangerous, although it might, but rather because what made the virus so dangerous was that nobody had immunity against it, so once it has become endemic it will infect fewer people and even those who end up infected will be much less at risk. Moreover, I will explain that, despite widespread anxiety about the emergence of new variants and the danger of immune evasion, the fact that SARS-CoV-2 is mutating will not prevent this outcome because of the way immunity works. Finally, I will argue that, although some people are calling to pursue the eradication of SARS-CoV-2 (as we have done with smallpox), we almost certainly couldn’t eradicate it even if we wanted to and that even if we could it wouldn’t be worth it.

As many countries are going through another wave of infections, including some where the vast majority of the population has been vaccinated, many are starting to despair that we’ll ever see the end of the pandemic. In this post, I will argue that, on the contrary, not only is the pandemic already on its way out, but the virus will be relatively harmless after it has become endemic. This is going to happen not because the SARS-CoV-2 will become intrinsically less dangerous, although it might, but rather because what made the virus so dangerous was that nobody had immunity against it, so once it has become endemic it will infect fewer people and even those who end up infected will be much less at risk. Moreover, I will explain that, despite widespread anxiety about the emergence of new variants and the danger of immune evasion, the fact that SARS-CoV-2 is mutating will not prevent this outcome because of the way immunity works. Finally, I will argue that, although some people are calling to pursue the eradication of SARS-CoV-2 (as we have done with smallpox), we almost certainly couldn’t eradicate it even if we wanted to and that even if we could it wouldn’t be worth it. Matter and energy are neither created nor destroyed, or so says modern physics. The subatomic substrate that adds up to the eyes scanning these words, the fingers holding them within sight and all the rest of your soft, unaccountable self, used to belong to other things—an apple or a cow, maybe—and they will belong to yet others in the future. What we are now, as long as we are, is a temporary contraction.

Matter and energy are neither created nor destroyed, or so says modern physics. The subatomic substrate that adds up to the eyes scanning these words, the fingers holding them within sight and all the rest of your soft, unaccountable self, used to belong to other things—an apple or a cow, maybe—and they will belong to yet others in the future. What we are now, as long as we are, is a temporary contraction. Researchers from MIT, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have developed a new way to deliver molecular therapies to cells. The system, called SEND, can be programmed to encapsulate and deliver different RNA cargoes. SEND harnesses natural proteins in the body that form virus-like particles and bind RNA, and it may provoke less of an immune response than other delivery approaches.

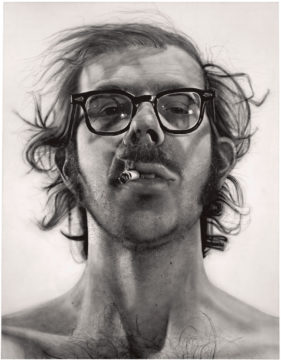

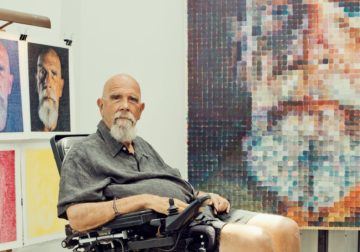

Researchers from MIT, the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have developed a new way to deliver molecular therapies to cells. The system, called SEND, can be programmed to encapsulate and deliver different RNA cargoes. SEND harnesses natural proteins in the body that form virus-like particles and bind RNA, and it may provoke less of an immune response than other delivery approaches. Mr. Close did not like to think of himself as a realist, photo or otherwise. In many ways he was closer to a conceptualist like Sol LeWitt, whose sculptures and murals were made according to preconceived rules and instructions. Tension between opposites like realism and abstraction, surface and depth, reality and illusion remained central to Mr. Close’s art throughout his career.

Mr. Close did not like to think of himself as a realist, photo or otherwise. In many ways he was closer to a conceptualist like Sol LeWitt, whose sculptures and murals were made according to preconceived rules and instructions. Tension between opposites like realism and abstraction, surface and depth, reality and illusion remained central to Mr. Close’s art throughout his career. Whatever museums ultimately decide to do about Mr. Close, some say they can no longer afford to simply present art without addressing the issues that surround the artist — that institutions must play a more active role in educating the public about the human beings behind the work.

Whatever museums ultimately decide to do about Mr. Close, some say they can no longer afford to simply present art without addressing the issues that surround the artist — that institutions must play a more active role in educating the public about the human beings behind the work. Something is amiss with democracy. Ask people from any or no political persuasion and they’re likely to give a similar story: contemporary politics has gone haywire because one side (or both) has lost touch with reality. We are living in a ‘post-truth’ partisan news hellscape that prioritises ‘feelings over facts’ and disregards the natural authority of the truth. But all sides seem to agree that there is a ‘truth’ that explains what really makes someone a woman, or an institution racist, or a politician fascist, in a way that compels acceptance from those who otherwise disagree. What we need to do is further emphasise the importance of science and reason, and perhaps sanction the overtly partisan media outlets that mislead otherwise good-natured people, then everyone will come to their senses and agree on things because they are true, because they reflect reality. Humans are rational, remember? Surely,

Something is amiss with democracy. Ask people from any or no political persuasion and they’re likely to give a similar story: contemporary politics has gone haywire because one side (or both) has lost touch with reality. We are living in a ‘post-truth’ partisan news hellscape that prioritises ‘feelings over facts’ and disregards the natural authority of the truth. But all sides seem to agree that there is a ‘truth’ that explains what really makes someone a woman, or an institution racist, or a politician fascist, in a way that compels acceptance from those who otherwise disagree. What we need to do is further emphasise the importance of science and reason, and perhaps sanction the overtly partisan media outlets that mislead otherwise good-natured people, then everyone will come to their senses and agree on things because they are true, because they reflect reality. Humans are rational, remember? Surely,  Global greenhouse gas emissions must peak in the next four years, coal and gas-fired power plants must close in the next decade and lifestyle and behavioural changes will be needed to avoid climate breakdown, according to the

Global greenhouse gas emissions must peak in the next four years, coal and gas-fired power plants must close in the next decade and lifestyle and behavioural changes will be needed to avoid climate breakdown, according to the  Ed Miliband, now freed from the burden of party leadership, has at last resolved the tension between centrist caution and radical ambition firmly in favor of the radical option. In his funny and self-deprecating new book, GO BIG: How To Fix Our World, Miliband makes the case that the only way forward now for center-left parties is to embrace a radical platform of institutional innovation. The book is therefore addressed not only to a British audience, but to parties and activists in the social democratic tradition elsewhere. It has strong resonances for those, such as partisans of the French Parti Socialiste or the German SPD, who face the dangerous prospect of their parties being beached by the tides of history. As its title suggests, GO BIG is a sustained argument for a level of political ambition that would cast the Labour Party’s Blairite era deep into the dustbin of history.

Ed Miliband, now freed from the burden of party leadership, has at last resolved the tension between centrist caution and radical ambition firmly in favor of the radical option. In his funny and self-deprecating new book, GO BIG: How To Fix Our World, Miliband makes the case that the only way forward now for center-left parties is to embrace a radical platform of institutional innovation. The book is therefore addressed not only to a British audience, but to parties and activists in the social democratic tradition elsewhere. It has strong resonances for those, such as partisans of the French Parti Socialiste or the German SPD, who face the dangerous prospect of their parties being beached by the tides of history. As its title suggests, GO BIG is a sustained argument for a level of political ambition that would cast the Labour Party’s Blairite era deep into the dustbin of history.