Liza Batkin in the NY Review of Books:

Liza Batkin in the NY Review of Books:

At the start of each summer, Supreme Court commentators are tasked with summarizing an unwieldy body of work—dozens of opinions on widely ranging areas of law, as many as nine different authors, concurrences, dissents, and a docket of unsigned orders. With a pool so big and incohesive, any attempt to sum it up runs the risk of being sunk by caveats. This term, the first with Amy Coney Barrett rounding out a decisive conservative majority, that risk was especially visible.

Many observers chose, as the overall theme of the term, unexpected unanimity. These commentators marveled at the number of cases in which liberal and conservative justices joined together to produce somewhat moderate decisions, framing it as a rebuke to predictions of a sharp rightward turn. But others were quick to point out the ways in which the Court’s decisions—especially those that came in a late flurry—were decidedly conservative, attacking voting rights, campaign finance laws, juvenile defendants, and unions. In other words, while the term wasn’t all bad, its handful of very bad decisions could not be treated as mere exceptions to an overall pattern of unanimity. Even where the justices did concur, moreover, it was to be wondered what might have been sacrificed for the sake of consensus.

More here.

Early in Werner Herzog’s 1974 documentary The Great Ecstasy of the Woodcarver Steiner, we find its subject, a champion “ski-flier,” in the studio where he works as an amateur woodcarver. Brushing his hand over a tree stump, Walter Steiner describes the forms his chisel will release: “I saw this bowl here, the way the shape recedes, it’s as if an explosion had happened, and the force cannot escape properly and is caught up everywhere.” Trapped force is not to be the film’s subject. Rather, its subject is fear—or, as Steiner calls it, “respect for the conditions.” From the ski-jump at Planica, Slovenia, he leaps out of his own imagination and into Herzog’s. Steiner’s coyness serves his strangely sober ecstasy. His afterimage haunts another work of creative documentation, composed at roughly the same time, some five hundred kilometers to the northeast. The Gentle Barbarian, Czech novelist Bohumil Hrabal’s memoir of his friendship with the painter and printmaker Vladimír Boudnik, depicts life as a more reckless leap of faith—one that lands not in the hands of God, but in a tightening rope.

Early in Werner Herzog’s 1974 documentary The Great Ecstasy of the Woodcarver Steiner, we find its subject, a champion “ski-flier,” in the studio where he works as an amateur woodcarver. Brushing his hand over a tree stump, Walter Steiner describes the forms his chisel will release: “I saw this bowl here, the way the shape recedes, it’s as if an explosion had happened, and the force cannot escape properly and is caught up everywhere.” Trapped force is not to be the film’s subject. Rather, its subject is fear—or, as Steiner calls it, “respect for the conditions.” From the ski-jump at Planica, Slovenia, he leaps out of his own imagination and into Herzog’s. Steiner’s coyness serves his strangely sober ecstasy. His afterimage haunts another work of creative documentation, composed at roughly the same time, some five hundred kilometers to the northeast. The Gentle Barbarian, Czech novelist Bohumil Hrabal’s memoir of his friendship with the painter and printmaker Vladimír Boudnik, depicts life as a more reckless leap of faith—one that lands not in the hands of God, but in a tightening rope. “It’s impossible to read about Simone de Beauvoir’s life without thinking of your own,” the biographer Hazel Rowley wrote in her foreword to the English translation of Beauvoir’s “Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter.” How did the image of this turbaned Frenchwoman in a severe, 1940s-style suit, sitting beside Jean-Paul Sartre at a table in the Cafe de Flore or La Coupole and writing all day long, become the avatar of a generation?

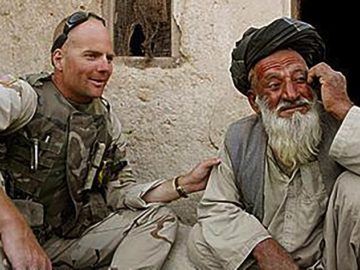

“It’s impossible to read about Simone de Beauvoir’s life without thinking of your own,” the biographer Hazel Rowley wrote in her foreword to the English translation of Beauvoir’s “Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter.” How did the image of this turbaned Frenchwoman in a severe, 1940s-style suit, sitting beside Jean-Paul Sartre at a table in the Cafe de Flore or La Coupole and writing all day long, become the avatar of a generation? AFGHANISTAN MAY NOT BE A NATION

AFGHANISTAN MAY NOT BE A NATION At one point last year, high schooler Rasha Alqahtani had finals coming up and 35 Zoom calls booked. To manage her busy schedule, she had duplicate calendars—one on Google Calendar, the other printed and placed behind her laptop, so that even a power outage wouldn’t derail her. The now-18-year-old from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, had laser-like focus on an extracurricular passion project: Creating a video-game tool to help diagnose teenagers with generalized anxiety disorder.

At one point last year, high schooler Rasha Alqahtani had finals coming up and 35 Zoom calls booked. To manage her busy schedule, she had duplicate calendars—one on Google Calendar, the other printed and placed behind her laptop, so that even a power outage wouldn’t derail her. The now-18-year-old from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, had laser-like focus on an extracurricular passion project: Creating a video-game tool to help diagnose teenagers with generalized anxiety disorder.

Resolving the great cosmological debate of the mid-20th century was not on their agenda. Yet in 1964, astrophysicists Arno A. Penzias and Robert W. “Bob” Wilson unexpectedly discovered a radio hiss that turned out to be relic radiation from the early universe. Much to their surprise, their finding, after being interpreted and published the following year, helped settle a long-standing argument about time and space. The Big Bang theory postulated the universe had been created with an initial burst of matter and energy, whereas the steady-state theory—its main rival—described no primordial eruption but rather a slow, continuous creation of material that remains ongoing. The Penzias-Wilson discovery of background radiation tipped the scale toward the Big Bang, away from the steady-state.

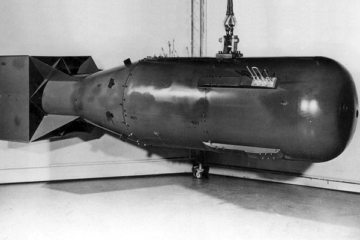

Resolving the great cosmological debate of the mid-20th century was not on their agenda. Yet in 1964, astrophysicists Arno A. Penzias and Robert W. “Bob” Wilson unexpectedly discovered a radio hiss that turned out to be relic radiation from the early universe. Much to their surprise, their finding, after being interpreted and published the following year, helped settle a long-standing argument about time and space. The Big Bang theory postulated the universe had been created with an initial burst of matter and energy, whereas the steady-state theory—its main rival—described no primordial eruption but rather a slow, continuous creation of material that remains ongoing. The Penzias-Wilson discovery of background radiation tipped the scale toward the Big Bang, away from the steady-state. “You can’t put the genie back in the bottle.” Those of us eager to get rid of nuclear weapons hear this a lot and at first glance it seems true; common sense suggests that neither genies nor nuclear weapons are readily rebottled. But this “common sense” is uncommonly wrong. Technologies have appeared throughout human history and just as the great majority of plant and animal species have eventually gone extinct, ditto for the great majority of technological genies. Only rarely have they been forcibly restrained or erased; nearly always they have simply been abandoned once people recognized they were inefficient, unsafe, outmoded, or sometimes just plain silly.

“You can’t put the genie back in the bottle.” Those of us eager to get rid of nuclear weapons hear this a lot and at first glance it seems true; common sense suggests that neither genies nor nuclear weapons are readily rebottled. But this “common sense” is uncommonly wrong. Technologies have appeared throughout human history and just as the great majority of plant and animal species have eventually gone extinct, ditto for the great majority of technological genies. Only rarely have they been forcibly restrained or erased; nearly always they have simply been abandoned once people recognized they were inefficient, unsafe, outmoded, or sometimes just plain silly. By now Sandra Oh’s hive of devoted fans have likely binged all six episodes of her

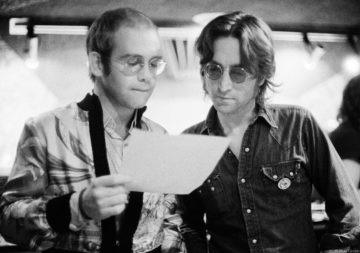

By now Sandra Oh’s hive of devoted fans have likely binged all six episodes of her  “I first met John Lennon through Tony King, who had moved to LA to become Apple Records’ general manager in the US. In fact, the first time I met John Lennon, he was dancing with Tony King. Nothing unusual in that, other than the fact that they weren’t in a nightclub, there was no music playing and Tony was in full drag as Queen Elizabeth II. They were at Capitol Records in Hollywood, where Tony’s new office was, shooting a TV advert for John’s forthcoming album Mind Games, and, for reasons best known to John, this was the big concept.

“I first met John Lennon through Tony King, who had moved to LA to become Apple Records’ general manager in the US. In fact, the first time I met John Lennon, he was dancing with Tony King. Nothing unusual in that, other than the fact that they weren’t in a nightclub, there was no music playing and Tony was in full drag as Queen Elizabeth II. They were at Capitol Records in Hollywood, where Tony’s new office was, shooting a TV advert for John’s forthcoming album Mind Games, and, for reasons best known to John, this was the big concept. What is it like to work in an Indian factory? Three documentaries (all currently streaming for free) begin to answer this troubling question. Anjali Monteiro and KP Jayasankar’s

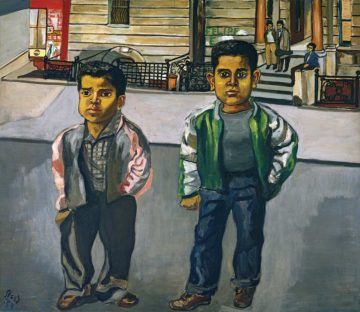

What is it like to work in an Indian factory? Three documentaries (all currently streaming for free) begin to answer this troubling question. Anjali Monteiro and KP Jayasankar’s  Neel took the call to realism to heart: She went out into the streets of Philadelphia to paint and attended a local sketch club where the models were ordinary people. (She was also part of the first generation of female art students allowed to study live male nudes.) The path of realism reflected how Neel understood her place in the world. “I had a conscience about going to art school,” she said. “Because when I’d go into the school, the scrub-women would be coming back from scrubbing office floors all night. It killed me that these old gray-headed women had to scrub floors, and I was going in there to draw Greek statues.”

Neel took the call to realism to heart: She went out into the streets of Philadelphia to paint and attended a local sketch club where the models were ordinary people. (She was also part of the first generation of female art students allowed to study live male nudes.) The path of realism reflected how Neel understood her place in the world. “I had a conscience about going to art school,” she said. “Because when I’d go into the school, the scrub-women would be coming back from scrubbing office floors all night. It killed me that these old gray-headed women had to scrub floors, and I was going in there to draw Greek statues.” JORGE LUIS BORGES: I dream every night. I dream before I go to sleep, and I dream after waking up. When I begin to say meaningless words, I’m seeing impossible things.

JORGE LUIS BORGES: I dream every night. I dream before I go to sleep, and I dream after waking up. When I begin to say meaningless words, I’m seeing impossible things. Not only do researchers often depict the brain and its functions much as mapmakers might draw nations on continents, but they do so “the way old-fashioned mapmakers” did, according to

Not only do researchers often depict the brain and its functions much as mapmakers might draw nations on continents, but they do so “the way old-fashioned mapmakers” did, according to  Those of us who argued against the war possessed no prophetic powers. I

Those of us who argued against the war possessed no prophetic powers. I