Ryan Ruby at the Poetry Foundation:

The prose poem begins life as a paradox and a provocation. On Christmas Day 1861, Charles Baudelaire sent a letter to Arsène Houssaye, the editor of L’Artiste and Le Presse, journals that had published some of Baudelaire’s short prose pieces. “Who among us has not dreamt, in moments of ambition, of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical without rhythm or rhyme, supple and staccato enough to adapt to the lyrical stirrings of the soul, the undulations of dreams, and sudden leaps of consciousness?” he wrote to Houssaye. The letter was first published as the preface to a posthumous collection of 50 prose pieces titled Petits Poèmes en prose (later, Le Spleen de Paris). Along with the neo-Biblical rhythms of Walt Whitman’s ever-expanding editions of Leaves of Grass, Baudelaire’s “little poems in prose” inspired a generation of French Modernists to undertake experiments in what they called vers libre or free verse: poetry untethered from meter, the feature that had distinguished it as a literary form, in the West at least, since Aristotle’s Rhetoric.

The prose poem begins life as a paradox and a provocation. On Christmas Day 1861, Charles Baudelaire sent a letter to Arsène Houssaye, the editor of L’Artiste and Le Presse, journals that had published some of Baudelaire’s short prose pieces. “Who among us has not dreamt, in moments of ambition, of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical without rhythm or rhyme, supple and staccato enough to adapt to the lyrical stirrings of the soul, the undulations of dreams, and sudden leaps of consciousness?” he wrote to Houssaye. The letter was first published as the preface to a posthumous collection of 50 prose pieces titled Petits Poèmes en prose (later, Le Spleen de Paris). Along with the neo-Biblical rhythms of Walt Whitman’s ever-expanding editions of Leaves of Grass, Baudelaire’s “little poems in prose” inspired a generation of French Modernists to undertake experiments in what they called vers libre or free verse: poetry untethered from meter, the feature that had distinguished it as a literary form, in the West at least, since Aristotle’s Rhetoric.

More here.

Ideally there’d be a change in our norms of conversation. Relying on an anecdote, arguing ad hominem — these should be mortifying. Of course no one can engineer social norms explicitly. But we know that norms can change, and if there are seeds that try to encourage the process, then there is some chance that it could go viral. On the other hand, a conclusion that I came to in the book is that the most powerful means of getting people to be more rational is not to concentrate on the people. Because people are pretty rational when it comes to their own lives. They get the kids clothed and fed and off to school on time, and they keep their jobs and pay their bills. But people hold beliefs not because they are provably true or false but because they’re uplifting, they’re empowering, they’re good stories. The key, though, is what kind of species are we? How rational is Homo sapiens? The answer can’t be that we’re just irrational in our bones, otherwise we could never have established the benchmarks of rationality against which we could say some people some of the time are irrational.

Ideally there’d be a change in our norms of conversation. Relying on an anecdote, arguing ad hominem — these should be mortifying. Of course no one can engineer social norms explicitly. But we know that norms can change, and if there are seeds that try to encourage the process, then there is some chance that it could go viral. On the other hand, a conclusion that I came to in the book is that the most powerful means of getting people to be more rational is not to concentrate on the people. Because people are pretty rational when it comes to their own lives. They get the kids clothed and fed and off to school on time, and they keep their jobs and pay their bills. But people hold beliefs not because they are provably true or false but because they’re uplifting, they’re empowering, they’re good stories. The key, though, is what kind of species are we? How rational is Homo sapiens? The answer can’t be that we’re just irrational in our bones, otherwise we could never have established the benchmarks of rationality against which we could say some people some of the time are irrational. Although the aim of conflict is as it ever was—to destroy or degrade the enemy’s capacity and will to fight—at every level from the individual enemy soldier to the economic and political system behind them, war has changed in character. This evolution is prompting new and urgent ethical questions, particularly in relation to remote unmanned military machines. Surveillance and hunter-killer drones such as the Predator and the Reaper have become commonplace on the modern battlefield and their continued use suggests—perhaps indeed presages—a future of war in which the fighting is done by machines independent of direct human control. This scenario prompts great anxieties.

Although the aim of conflict is as it ever was—to destroy or degrade the enemy’s capacity and will to fight—at every level from the individual enemy soldier to the economic and political system behind them, war has changed in character. This evolution is prompting new and urgent ethical questions, particularly in relation to remote unmanned military machines. Surveillance and hunter-killer drones such as the Predator and the Reaper have become commonplace on the modern battlefield and their continued use suggests—perhaps indeed presages—a future of war in which the fighting is done by machines independent of direct human control. This scenario prompts great anxieties. America’s school board meetings are out of control.

America’s school board meetings are out of control. Eighty years ago, in the fall of 1941, the musical Best Foot Forward opened on Broadway. Written by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane, who would go on to write the songs for the classic film Meet Me in St. Louis a few years later, Best Foot Forward is not a classic—it’s a piece of fluff about a prep-school boy who invites a Hollywood actress to be his prom date, to the annoyance of his actual girlfriend. But it ran on Broadway for almost a year and then was turned into a movie, with Lucille Ball as the starlet, that’s still worth watching.

Eighty years ago, in the fall of 1941, the musical Best Foot Forward opened on Broadway. Written by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane, who would go on to write the songs for the classic film Meet Me in St. Louis a few years later, Best Foot Forward is not a classic—it’s a piece of fluff about a prep-school boy who invites a Hollywood actress to be his prom date, to the annoyance of his actual girlfriend. But it ran on Broadway for almost a year and then was turned into a movie, with Lucille Ball as the starlet, that’s still worth watching. In late summer of 1976, two colleagues at Oxford University Press, Michael Rodgers and Richard Charkin, were discussing a book on evolution soon to be published. It was by a first-time author, a junior zoology don in town, and had been given an initial print run of 5,000 copies. As the two publishers debated the book’s fate, Charkin confided that he doubted it would sell more than 2,000 copies. In response, Rodgers, who was the editor who had acquired the manuscript, suggested a bet whereby he would pay Charkin £1 for every 1,000 copies under 5,000, and Charkin was to buy Rodgers a pint of beer for every 1,000 copies over 5,000. By now, the book is one of OUP’s most successful titles, and it has sold more than a million copies in dozens of languages, spread across four editions. That book was Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene, and Charkin is ‘holding back payment in the interests of [Rodgers’s] health and wellbeing’.

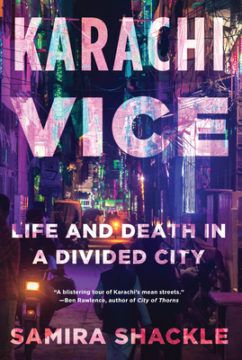

In late summer of 1976, two colleagues at Oxford University Press, Michael Rodgers and Richard Charkin, were discussing a book on evolution soon to be published. It was by a first-time author, a junior zoology don in town, and had been given an initial print run of 5,000 copies. As the two publishers debated the book’s fate, Charkin confided that he doubted it would sell more than 2,000 copies. In response, Rodgers, who was the editor who had acquired the manuscript, suggested a bet whereby he would pay Charkin £1 for every 1,000 copies under 5,000, and Charkin was to buy Rodgers a pint of beer for every 1,000 copies over 5,000. By now, the book is one of OUP’s most successful titles, and it has sold more than a million copies in dozens of languages, spread across four editions. That book was Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene, and Charkin is ‘holding back payment in the interests of [Rodgers’s] health and wellbeing’. I moved to Karachi in the aftermath of riots, arriving to smashed shop windows and the smell of burning tires. It was 2012 and the city had been engulfed by protests against a YouTube video that made offensive statements about the Prophet Muhammad. The city’s few remaining cinemas had been attacked, and churches had taken extra security precautions, lest the mob hold Pakistan’s Christians accountable for the crimes of the American filmmakers. The scale of destruction was disproportionate to the offence itself. I was a Londoner moving to my mother’s hometown, a place I had visited only once since childhood. This was an immediate introduction to the discontent that bubbled beneath the surface of the city, always ready to erupt into violence.

I moved to Karachi in the aftermath of riots, arriving to smashed shop windows and the smell of burning tires. It was 2012 and the city had been engulfed by protests against a YouTube video that made offensive statements about the Prophet Muhammad. The city’s few remaining cinemas had been attacked, and churches had taken extra security precautions, lest the mob hold Pakistan’s Christians accountable for the crimes of the American filmmakers. The scale of destruction was disproportionate to the offence itself. I was a Londoner moving to my mother’s hometown, a place I had visited only once since childhood. This was an immediate introduction to the discontent that bubbled beneath the surface of the city, always ready to erupt into violence. Cryptocurrencies have emerged as one of the most captivating, yet head-scratching, investments in the world. They soar in value. They crash. They’ll change the world, their fans claim, by displacing traditional currencies like the dollar, rupee or ruble. They’re named after

Cryptocurrencies have emerged as one of the most captivating, yet head-scratching, investments in the world. They soar in value. They crash. They’ll change the world, their fans claim, by displacing traditional currencies like the dollar, rupee or ruble. They’re named after  Purple morning glories creep and sprawl against a white fence, embracing a sculpture of sorts, wooden arms akimbo; a blue plastic bin flipped over. One can almost hear the crunch of the photographer’s foot against the dried grass. The photographs of Sue Palmer Stone exist somewhere between the extremes of exuberance and decay, fragility and strength, loss and playfulness.

Purple morning glories creep and sprawl against a white fence, embracing a sculpture of sorts, wooden arms akimbo; a blue plastic bin flipped over. One can almost hear the crunch of the photographer’s foot against the dried grass. The photographs of Sue Palmer Stone exist somewhere between the extremes of exuberance and decay, fragility and strength, loss and playfulness. Before

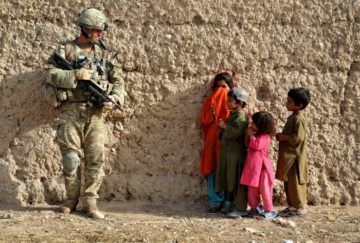

Before  Thomas Meaney in the LRB (Photo by

Thomas Meaney in the LRB (Photo by  Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar (Photo by

Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar (Photo by  Faisal Devji in Boston Review:

Faisal Devji in Boston Review: