Tad Friend in The New Yorker:

We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand.

We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand.

You may have seen one advertised online, among the “weird tricks” to erase your tummy fat and your student loans. It’s MasterClass, a site that promises to disclose the secrets of everything from photography to comedy to wilderness survival. The company’s recent ad, “Lessons on Greatness. Gretzky,” encapsulates the pitch: a class taught by the greatest hockey player ever, full of insights not just for aspiring players but for anyone eager to achieve extraordinary things. In the seminar, Wayne Gretzky tells us that as a kid he’d watch games and diagram the puck’s movements on a sketch of a rink, which taught him to “skate to where the puck is gonna be.” Likewise, Martin Scorsese says in his class that he used to storyboard scenes from movies he admired, such as the chariot race in “Ben-Hur.” The idea that mastery can be achieved by attentive emulation of the masters is the site’s foundational promise. James Cameron, in his class, suggests that the path to glory consists of only one small step. “There’s a moment when you’re just a fan, and there’s a moment when you’re a filmmaker,” he assures us. “All you have to do is pick up a camera and start shooting.”

When MasterClass launched, in 2015, it offered three courses: Dustin Hoffman on acting, James Patterson on writing, and Serena Williams on tennis. Today, there are a hundred and thirty, in categories from business to wellness. During the pandemic lockdown, demand was up as much as tenfold from the previous year; last fall, when the site had a back-to-school promotion, selling an annual subscription for a dollar instead of a hundred and eighty dollars, two hundred thousand college students signed up in a day. MasterClass will double in size this year, to six hundred employees, as it launches in the U.K., France, Germany, and Spain. It’s a Silicon Valley investor’s dream, a rolling juggernaut of flywheels and network effects dedicated to helping you, as the instructor Garry Kasparov puts it, “upgrade your software.”

The classes are crammed with pro tips and are often highly entertaining. Neil Gaiman explains the comfort and tedium of genre fiction by noting that, in such stories, the plot exists only to prevent all the shoot-outs and cattle stampedes from happening at the same time. Serena Williams advises playing the backhands of big-chested women, because “larger boobs” hinder shoulder rotation. And the singer St. Vincent observes that the artist’s job is to metabolize shame.

More here.

As a novel, “Dune” has never been unconditionally admired. I know sophisticated readers, devoted science fiction fans, who can’t stand it, finding Herbert’s prose inept, the action ponderous, and the whole book clumsy and tedious. But sf readers are contentious, often cruelly so, and nearly all of the field’s most beloved novels and series also have cogent and vocal detractors: Isaac Asimov’s “Foundation” trilogy is dismissed as period pulp; Robert A. Heinlein’s “Starship Troopers” and “Stranger in a Strange Land” preach either militaristic jingoism or pretentious ’60s claptrap; Samuel R. Delany’s “Dhalgren” is well nigh unreadable and Gene Wolfe’s “The Book of the New Sun” too subtle, too theological, too clever by half. Perhaps so. Yet imaginative works that people still argue about — and “Dune” certainly belongs in this category — demonstrate their continuing vitality and relevance. They remain — to borrow a vogue phrase — part of the conversation.

As a novel, “Dune” has never been unconditionally admired. I know sophisticated readers, devoted science fiction fans, who can’t stand it, finding Herbert’s prose inept, the action ponderous, and the whole book clumsy and tedious. But sf readers are contentious, often cruelly so, and nearly all of the field’s most beloved novels and series also have cogent and vocal detractors: Isaac Asimov’s “Foundation” trilogy is dismissed as period pulp; Robert A. Heinlein’s “Starship Troopers” and “Stranger in a Strange Land” preach either militaristic jingoism or pretentious ’60s claptrap; Samuel R. Delany’s “Dhalgren” is well nigh unreadable and Gene Wolfe’s “The Book of the New Sun” too subtle, too theological, too clever by half. Perhaps so. Yet imaginative works that people still argue about — and “Dune” certainly belongs in this category — demonstrate their continuing vitality and relevance. They remain — to borrow a vogue phrase — part of the conversation.

In May 1453, Ottoman military forces under Sultan Mehmed II captured the once great Byzantine capital of Constantinople, now Istanbul. It was a landmark moment. What was viewed as one of the greatest cities of Christendom, and described by the sultan as “the second Rome”, had fallen to Muslim conquerors. The sultan even called himself “caesar”.

In May 1453, Ottoman military forces under Sultan Mehmed II captured the once great Byzantine capital of Constantinople, now Istanbul. It was a landmark moment. What was viewed as one of the greatest cities of Christendom, and described by the sultan as “the second Rome”, had fallen to Muslim conquerors. The sultan even called himself “caesar”. We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand.

We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand. In the last chapter of his first book, Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, Spencer Ackerman reminds his readers of Bernie Sanders’s June 2019 assertion: “There is a straight line from the decision to reorient U.S. national-security strategy around terrorism after 9/11 to placing migrant children in cages on our southern border.”

In the last chapter of his first book, Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, Spencer Ackerman reminds his readers of Bernie Sanders’s June 2019 assertion: “There is a straight line from the decision to reorient U.S. national-security strategy around terrorism after 9/11 to placing migrant children in cages on our southern border.” Academics use the category of magic, well, often magically, to dismiss the phenomenon they are studying, to banish the subject matter from living contact with their present reality. Ancient philosophy is over there, good and dead, and we enlightened modern philosophers and scholars are over here, living, present, pristine and modern, washed clean of ancient superstitions. But magic is rather sticky, hard to wash off from the hands or the delicate underside of the modern mind, to which it clings like a sinister visitor who has always arrived, but is still waiting to announce itself.

Academics use the category of magic, well, often magically, to dismiss the phenomenon they are studying, to banish the subject matter from living contact with their present reality. Ancient philosophy is over there, good and dead, and we enlightened modern philosophers and scholars are over here, living, present, pristine and modern, washed clean of ancient superstitions. But magic is rather sticky, hard to wash off from the hands or the delicate underside of the modern mind, to which it clings like a sinister visitor who has always arrived, but is still waiting to announce itself. Take the word “understand;” in daily communication we rarely parse it’s implications, but the word itself is a spatial metaphor. Linguist Guy Deutscher explains in

Take the word “understand;” in daily communication we rarely parse it’s implications, but the word itself is a spatial metaphor. Linguist Guy Deutscher explains in  For the longest part of our history, humans lived as hunter-gatherers who neither experienced economic growth nor worried about its absence. Instead of working many hours each day in order to acquire as much as possible, our nature—insofar as we have one—has been to do the minimum amount of work necessary to underwrite a good life.

For the longest part of our history, humans lived as hunter-gatherers who neither experienced economic growth nor worried about its absence. Instead of working many hours each day in order to acquire as much as possible, our nature—insofar as we have one—has been to do the minimum amount of work necessary to underwrite a good life. Sometimes our most precious cultural institutions fail to live up to their high educational and moral commitments and responsibilities. These failures especially damage the social fabric because they tend to harm many people who rely on them and tarnish the high ideals that the institutions claim to exemplify.

Sometimes our most precious cultural institutions fail to live up to their high educational and moral commitments and responsibilities. These failures especially damage the social fabric because they tend to harm many people who rely on them and tarnish the high ideals that the institutions claim to exemplify. We don’t know his real name. In early inscriptions it appears as Yhw, Yhwh, or simply Yh; but we don’t know how it was spoken. He has come to be known as Yahweh. Perhaps it doesn’t matter; by the third century BCE his name had been declared unutterable. We know him best as God.

We don’t know his real name. In early inscriptions it appears as Yhw, Yhwh, or simply Yh; but we don’t know how it was spoken. He has come to be known as Yahweh. Perhaps it doesn’t matter; by the third century BCE his name had been declared unutterable. We know him best as God. The body’s constellation of gut bacteria has been linked with various aging-associated illnesses, including cardiovascular disease and type 2

The body’s constellation of gut bacteria has been linked with various aging-associated illnesses, including cardiovascular disease and type 2  To this day nobody knows exactly what transpired in Selamon on that April night, in the year 1621, except that a lamp fell to the floor in the building where Martijn Sonck, a Dutch official, was billeted.

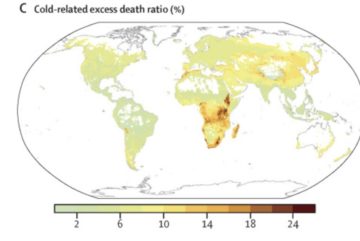

To this day nobody knows exactly what transpired in Selamon on that April night, in the year 1621, except that a lamp fell to the floor in the building where Martijn Sonck, a Dutch official, was billeted. People are most likely to die of extreme cold in Sub-Saharan Africa, and most likely to die of extreme heat in Greenland, Norway, and various very high mountains. You’re reading that right – the cold deaths are centered in the warmest areas, and vice versa.

People are most likely to die of extreme cold in Sub-Saharan Africa, and most likely to die of extreme heat in Greenland, Norway, and various very high mountains. You’re reading that right – the cold deaths are centered in the warmest areas, and vice versa. Francis Fukuyama: It’s a really old doctrine. And I think there are several reasons that it’s been around for such a long time: A pragmatic, political reason; a moral reason; and then there’s a very powerful economic one.

Francis Fukuyama: It’s a really old doctrine. And I think there are several reasons that it’s been around for such a long time: A pragmatic, political reason; a moral reason; and then there’s a very powerful economic one.