Category: Recommended Reading

People weren’t so lazy back then

Juan Siliezar in The Harvard Gazette:

Contemporary Americans have access to custom workout routines, fancy gyms, and high-end home equipment like Peloton machines. Even so, when it comes to physical activity, our forebears of two centuries ago beat us by about 30 minutes a day, according to a new Harvard study.

Contemporary Americans have access to custom workout routines, fancy gyms, and high-end home equipment like Peloton machines. Even so, when it comes to physical activity, our forebears of two centuries ago beat us by about 30 minutes a day, according to a new Harvard study.

Researchers from the lab of evolutionary biologist Daniel E. Lieberman used data on falling body temperatures and changing metabolic rates to compare current levels of physical activity in the United States with those of the early 19th century. The work is described in Current Biology. The scientists found that Americans’ resting metabolic rate — the total number of calories burned when the body is completely at rest — has fallen by about 6 percent since 1820, which translates to 27 fewer minutes of daily exercise. The culprit, the authors say, is technology.

“Instead of walking to work, we take cars or trains; instead of manual labor in factories, we use machines,” said Andrew K. Yegian, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Human and Evolutionary Biology and the paper’s lead author. “We’ve made technology to do our physical activity for us. … Our hope is that this helps people think more about the long-term changes of activity that have come with our changes in lifestyle and technology.”

While it’s been well documented that technological and social changes have reduced levels of physical activity the past two centuries, the precise drop-off had never been calculated. The paper puts a quantitative number to the literature and shows that historical records of resting body temperature may be able to serve as a measure of population-level physical activity.

More here.

Futurists have their heads in the clouds

Erik Hoel in Substack:

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

To see what I mean more specifically: 2050, that super futuristic year, is only 29 years out, so it is exactly the same as predicting what the world would look like today back in 1992. How would one proceed in such a prediction? Many of the most famous futurists would proceed by imagining a sci-fi technology that doesn’t exist (like brain uploading, magnetic floating cars, etc), with the assumption that these nonexistent technologies will be the most impactful. Yet what was most impactful from 1992 were technologies or trends already in their nascent phases, and it was simply a matter of choosing what to extrapolate.

For instance, cellular phones, personal computers, and the internet all existed back in 1992, although in comparatively inchoate stages of development. So did the beginning of the rise of college costs, the start of an urban renaissance, a major crime bill was being passed, there were increasing standards of living, especially in entertainment, and meanwhile globalization was in full swing, the soviet union had already collapsed, islamic terrorism was considered a major threat, the big growing debates were PC culture and health care reform, and the USA was without a doubt the world’s leading superpower. Put all those things together and you would have had at least an adumbration of today. Stuff takes a long time to play out, often several generations. The central social and political ideas of our culture were established in the 1960s and 70s and took a slow half-century to climb from obscure academic monographs to Super Bowl ads.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Controlled Burn

Seven trees come down

and then the trees are burned

to rid the yard of branches, brambles.

Smoke drifts thick through the coat

of the German Shepherd who belongs

to the tree cutters. He snaps a twig

that an hour ago hung in the sky.

He breaks it, joyfully mossing his mouth.

It makes the sound of biscotti.

This morning in the house where Mike grew up

I pointed at a trapdoor outside our bedroom,

leading to an attic we’ve never seen.

He said three times I feel like I’m going

to wake up. We sleepwalk through the day

to the dull whine of the chainsaw.

We know now trees are social creatures,

feeding sugar to the young

and the sick through their roots

They can keep alive a cut stump for decades—

the time it will take the collagen

to abandon my face and cartilage in my knees

to grind down to nothingness.

When I was a child, afraid of dying,

my father told me there was no heaven

but we stay in the earth, alchemize

into trees. I can’t tell you the horror

I felt then, having expected angels.

The smoke thins from a billow to a plume

while the men turn trunks into logs

and the dog works over a new stick.

He was named for a city in New York

that was named for an ancient city

that burned, but he doesn’t know.

The dog loves his stick the way I love

my mind, worrying the same grooves

into whatever fresh thing he’s given.

by Laura Creste

from The Yale Review

Friday, October 29, 2021

Yesterday’s Mythologies

Ryan Ruby in Sidecar:

There is a world, not too dissimilar from our own, in which Jonathan Franzen is a professor of creative writing at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest. He still has his bylines at the New Yorker and Harper’s (in fact, he writes for them more frequently); he still has his books (even if they’re all a bit shorter, one of them is a collection of short stories, and his translation of Spring Awakening lives with his unpublished notes on Karl Kraus in the Amish-made drawer of his ‘archive’); he still has his awards (except his NBA is now an NEA). Despite his misgivings about the effect of social media on print culture, he also has a Facebook page, which he uses to promote his readings and share photos of his outings with the local birding society, and a Twitter account, which he uses to retweet positive reviews and post about Julian Assange. Aside from his anxiety about how much time teaching and administrative duties take away from his ‘real work’ as a novelist, whether his diminishing royalty checks will be enough to cover his mortgage and his adopted son’s college tuition, and whether it would be wise to keep flirting with the sole female member of his small group of student acolytes, the greatest drama in his life occurs when he periodically becomes the main character on Twitter for saying something hopelessly out of touch – pile-ons he less-than-discreetly attributes to other writers’ envy for his hard-won success.

There is a world, not too dissimilar from our own, in which Jonathan Franzen is a professor of creative writing at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest. He still has his bylines at the New Yorker and Harper’s (in fact, he writes for them more frequently); he still has his books (even if they’re all a bit shorter, one of them is a collection of short stories, and his translation of Spring Awakening lives with his unpublished notes on Karl Kraus in the Amish-made drawer of his ‘archive’); he still has his awards (except his NBA is now an NEA). Despite his misgivings about the effect of social media on print culture, he also has a Facebook page, which he uses to promote his readings and share photos of his outings with the local birding society, and a Twitter account, which he uses to retweet positive reviews and post about Julian Assange. Aside from his anxiety about how much time teaching and administrative duties take away from his ‘real work’ as a novelist, whether his diminishing royalty checks will be enough to cover his mortgage and his adopted son’s college tuition, and whether it would be wise to keep flirting with the sole female member of his small group of student acolytes, the greatest drama in his life occurs when he periodically becomes the main character on Twitter for saying something hopelessly out of touch – pile-ons he less-than-discreetly attributes to other writers’ envy for his hard-won success.

In the actual world, however, Franzen’s face has been captioned ‘Great American Novelist’ on the cover of Time. His publicist has not been too embarrassed to say that he is ‘universally regarded as the leading novelist of his generation’. In this world, he has the time, money, and freedom to do nothing but write what he pleases. Before he finishes a single sentence, he can take for granted that there will be a wide audience for it.

More here.

How to Memorize the Un-Memorizable

Marcus du Sautoy in Literary Hub:

Although I’ve successfully learned the language of mathematics, it has always frustrated me that I couldn’t master those more unpredictable languages like French or Russian that I’d tried to learn in hopes of becoming a spy. Although Gauss too left his love of languages behind to pursue a career in mathematics, he did actually return to the challenge of learning new languages in later life, such as Sanskrit and Russian. At the age of 64, after two years of study, he had mastered Russian well enough to read Pushkin in the original. Inspired by Gauss’s example, I’ve decided to revisit my attempts at learning Russian.

Although I’ve successfully learned the language of mathematics, it has always frustrated me that I couldn’t master those more unpredictable languages like French or Russian that I’d tried to learn in hopes of becoming a spy. Although Gauss too left his love of languages behind to pursue a career in mathematics, he did actually return to the challenge of learning new languages in later life, such as Sanskrit and Russian. At the age of 64, after two years of study, he had mastered Russian well enough to read Pushkin in the original. Inspired by Gauss’s example, I’ve decided to revisit my attempts at learning Russian.

One of the problems I have is simply remembering strange new words. Spotting patterns is my shortcut to memory. But what if there are no patterns? I wanted to know if there might be alternative shortcuts I could try. Who better to ask than Ed Cooke, a Grand Master of Memory and founder of a new venture for learning languages called Memrise?

More here.

Lost in Work: Escaping Capitalism

Madeline Lane-McKinley in the Boston Review:

If there is a utopian kernel to be found in this pandemic, so replete with dystopian terror, it is most certainly that each day more and more people have grown to hate the world of work. Some of us, certainly a lucky few, might even enjoy our jobs, or certain aspects of them, but all the same, work under capitalism has become increasingly legible as a system of false promises—deferred freedom, self-actualization, leisure, joy, safety, or whatever else we might value that cannot be reduced to the accumulation of capital.

If there is a utopian kernel to be found in this pandemic, so replete with dystopian terror, it is most certainly that each day more and more people have grown to hate the world of work. Some of us, certainly a lucky few, might even enjoy our jobs, or certain aspects of them, but all the same, work under capitalism has become increasingly legible as a system of false promises—deferred freedom, self-actualization, leisure, joy, safety, or whatever else we might value that cannot be reduced to the accumulation of capital.

At the center of this network of false promises is the myth of the labor of love, currently “cracking under its own weight,” as labor journalist Sarah Jaffe argues in her recent book Work Won’t Love You Back, “because work itself no longer works.” Historically this myth applied to the work of caretaking as a way to naturalize the unwaged or low-waged labor of women, from childcare, eldercare, and housework to teaching and nursing. Today, “the conditions under which ‘essential’ workers had to report to the job,” Jaffe notes, “revealed the coercion at the heart of the labor relation.”

More here.

Stephen Fry on American vs British Comedy

On ‘The Magician’ by Colm Tóibín

Enda O’Doherty at The Dublin Review of Books:

Colm Tóibín presents us with one account of Mann’s gradual progress away from German nationalism. It might not be the last word on what seems to have been a complex and tortured journey, but it functions well in the context of the demands of a novel, where the shifts in perspective must be presented dramatically and are often portrayed through Thomas’s interactions with others, principally members of his large and turbulent family. First and most important of these is his wife, Katia Pringsheim, who is deeply suspicious of his friendship with the nationalist (and later Nazi) writer Ernst Bertram. On the outbreak of the First World War Katia asks her husband to consider how they would feel if their two boys, Klaus and Golo, were old enough to be conscripted, “and we were waiting here each day for news of them”: “And all because of some idea.”

Colm Tóibín presents us with one account of Mann’s gradual progress away from German nationalism. It might not be the last word on what seems to have been a complex and tortured journey, but it functions well in the context of the demands of a novel, where the shifts in perspective must be presented dramatically and are often portrayed through Thomas’s interactions with others, principally members of his large and turbulent family. First and most important of these is his wife, Katia Pringsheim, who is deeply suspicious of his friendship with the nationalist (and later Nazi) writer Ernst Bertram. On the outbreak of the First World War Katia asks her husband to consider how they would feel if their two boys, Klaus and Golo, were old enough to be conscripted, “and we were waiting here each day for news of them”: “And all because of some idea.”

The doings of the Mann family provide much of the necessary human interest of The Magician. Highly gifted and highly-strung, they are a problem for Thomas from the start, but all of them, and in particular the eldest pair, Erika and Klaus, have the function, along with his brother/rival Heinrich, of slowly pulling him towards a braver, more radical opposition to Nazism.

more here.

Colm Tóibín | The Magician

The History of How Coal Made Britain

Richard Vinen at The Literary Review:

In many ways, the age of coal was terrible. Thousands died in mining accidents and thousands more of diseases that they had contracted in pits. When a slag heap at Aberfan collapsed on top of the village primary school in 1966, at the inquest the coroner talked of ‘asphyxia and multiple injuries’, but one miner shouted that the words that he wanted on his child’s death certificate were ‘buried alive by the NCB’. And yet the British remember this age with a curious nostalgia. What could be more reassuringly familiar than the dense, smoky fogs of Sherlock Holmes’s London or the fact that the detective keeps his cigars in the coal scuttle? In Mike Leigh’s film High Hopes, the disappearance of coal is used as a metaphor for the rise of the rootless, yuppie society of the 1980s. ‘Mum, look what they’ve done to your coal hole,’ says one character when she sees how the new owners of a former council house have adapted the cellar. A Hovis television advertisement of 2008, celebrating the last hundred years of British history, featured miners, along with V-E Day parties and a Churchill speech, though, revealingly, it depicted a scene of a picket line in 1984 rather than of an actual working mine.

In many ways, the age of coal was terrible. Thousands died in mining accidents and thousands more of diseases that they had contracted in pits. When a slag heap at Aberfan collapsed on top of the village primary school in 1966, at the inquest the coroner talked of ‘asphyxia and multiple injuries’, but one miner shouted that the words that he wanted on his child’s death certificate were ‘buried alive by the NCB’. And yet the British remember this age with a curious nostalgia. What could be more reassuringly familiar than the dense, smoky fogs of Sherlock Holmes’s London or the fact that the detective keeps his cigars in the coal scuttle? In Mike Leigh’s film High Hopes, the disappearance of coal is used as a metaphor for the rise of the rootless, yuppie society of the 1980s. ‘Mum, look what they’ve done to your coal hole,’ says one character when she sees how the new owners of a former council house have adapted the cellar. A Hovis television advertisement of 2008, celebrating the last hundred years of British history, featured miners, along with V-E Day parties and a Churchill speech, though, revealingly, it depicted a scene of a picket line in 1984 rather than of an actual working mine.

more here.

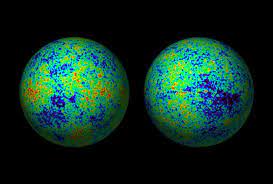

A new theory puts dark matter on the chopping block

Nicole Karlis in Salon:

What if dark matter didn’t exist? Sure, scientists have never observed it, but they believe it exists because of apparent gravitational effects. But what if our current understanding of gravity was just plain wrong?

What if dark matter didn’t exist? Sure, scientists have never observed it, but they believe it exists because of apparent gravitational effects. But what if our current understanding of gravity was just plain wrong?

The question has been raised over the last several decades, but typically when a proposed modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND) theory is put forth it has too big a blindspot to be taken seriously in the scientific community. In this case, the theory arguing against the existence of dark matter can’t account for observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is the leftover glow of the Big Bang or explain what happens at a larger scale with galaxies. Certainly such a discovery would be a significant change in the world of physics and have a remarkable impact on science.

This month however, researchers Constantinos Skordis and Tom Zlosnik from the Czech Academy of Sciences published a paper in the journal Physical Review Letters suggesting that a new modification to the parameters of Newton’s theory of gravity could provide an answer as to why dark matter has yet to be detected. And unlike previously proposed MOND theories, this one just might stick because the new proposal can match observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is a key detail that has lacked in the previous MOND-like theories.

…Dark matter is estimated to make up 27% of the universe’s total mass and energy, which is nearly five times more than the “normal” matter that comprises planets and stars. True to its name, dark matter is hard to directly observe. So far, none of the efforts to figure out the nature of the dark matter have gone very far. Yet astronomers are quite convinced it exists because of the huge gravitational effect it has on galaxies and the stars that live within them. As far as anyone can tell, dark matter is extremely non-interacting: just as humans walk through a still room barely noticing the atmosphere that surrounds us, dark matter seems to barely ever touch, even faintly, the normal matter that it hovers around. It is bound to our world by gravity only, and only tugs on other things that also possess gravity.

More here.

We’re mapping the brain in amazing detail—but our brain can’t understand the picture

Grigori Guitchounts in Nautilus:

On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement.

On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement.

Printed on paper, the dataset would fill 116 billion pages, double-spaced. When I recently finished writing the story of my data, the magnum opus fit on fewer than two dozen printed pages. Performing the experiments turned out to be the easy part. I had spent the last year agonizing over the data, observing and asking questions. The answers left out large chunks that did not pertain to the questions, like a map leaves out irrelevant details of a territory. But, as massive as my dataset sounds, it represents just a tiny chunk of a dataset taken from the whole brain. And the questions it asks—Do neurons in the visual cortex do anything when an animal can’t see? What happens when inputs to the visual cortex from other brain regions are shut off?—are small compared to the ultimate question in neuroscience: How does the brain work?

The nature of the scientific process is such that researchers have to pick small, pointed questions. Scientists are like diners at a restaurant: We’d love to try everything on the menu, but choices have to be made. And so we pick our field, and subfield, read up on the hundreds of previous experiments done on the subject, design and perform our own experiments, and hope the answers advance our understanding. But if we have to ask small questions, then how do we begin to understand the whole? Neuroscientists have made considerable progress toward understanding brain architecture and aspects of brain function. We can identify brain regions that respond to the environment, activate our senses, generate movements and emotions. But we don’t know how different parts of the brain interact with and depend on each other. We don’t understand how their interactions contribute to behavior, perception, or memory. Technology has made it easy for us to gather behemoth datasets, but I’m not sure understanding the brain has kept pace with the size of the datasets.

More here.

Friday Poem

Greetings to the People of Europe!

Over land and sea, your fathers came to Africa

and unpacked bibles by the thousand,

filling our ancestors with words of love:

if someone slaps your right cheek,

let him slap your left cheek too!

if someone takes your coat,

let him have your trousers too!

now we, their children’s children,

inheriting the words your fathers left behind,

our bodies slapped and stripped

by our lifetime presidents,

are braving seas and leaky boats,

cold waves of fear – let salt winds punch

our faces and your coast-guards

pluck us from the water like oily birds!

but here we are at last to knock

at your front door,

hoping against hope that you remember

all the lovely words your fathers preached at ours.

by Alemu Tebeje, © 2020,

from: Songs We Learn From Trees

publisher: Carcanet Classics, Manchester, 2020

Translation: Chris Beckett and Alemu Tebeje, 2020

Thursday, October 28, 2021

A Closer Look at the Math of American Inequality

Matthew Stewart in Literary Hub:

The story of rising economic inequality is by now so familiar that it fits easily onto a T-shirt. But the way the story is told is often imprecise enough to leave out much of the plot. “We are the 99 percent” sounds righteous enough, but it’s a slogan, not an analysis. It suggests that the whole issue is about “them,” a tiny group of crazy rich people, who are nothing at all like “us.” But that’s not how inequality has ever worked. You can glimpse the outlines of the problem if you take a closer look at the math of inequality.

The story of rising economic inequality is by now so familiar that it fits easily onto a T-shirt. But the way the story is told is often imprecise enough to leave out much of the plot. “We are the 99 percent” sounds righteous enough, but it’s a slogan, not an analysis. It suggests that the whole issue is about “them,” a tiny group of crazy rich people, who are nothing at all like “us.” But that’s not how inequality has ever worked. You can glimpse the outlines of the problem if you take a closer look at the math of inequality.

Supposing we stick for the moment with the questionable suggestion that “we” are merely a collection of percentiles in the wealth distribution tables—and I will question that suggestion in a moment—the first thing to note is that “99 percent” is not the right number. Contrary to popular wisdom, it is not the “top 1 percent” but the top 0.1 percent of households that have captured essentially all of the increase in the relative concentration of wealth over the past fifty years.

More here.

Can AI’s Voracious Appetite for Data Be Tamed?

John McQuaid in Undark:

The problems originate in the mundane practices of computer coding. Machine learning reveals patterns in data — such algorithms learn, for example, how to identify common features of “cupness” from processing many, many pictures of cups. The approach is increasingly used by businesses and government agencies; in addition to facial recognition systems, it’s behind Facebook’s news feed and targeting of advertisements, digital assistants such as Siri and Alexa, guidance systems for autonomous vehicles, some medical diagnoses, and more.

The problems originate in the mundane practices of computer coding. Machine learning reveals patterns in data — such algorithms learn, for example, how to identify common features of “cupness” from processing many, many pictures of cups. The approach is increasingly used by businesses and government agencies; in addition to facial recognition systems, it’s behind Facebook’s news feed and targeting of advertisements, digital assistants such as Siri and Alexa, guidance systems for autonomous vehicles, some medical diagnoses, and more.

To learn, algorithms need massive datasets. But as the applications grow more varied and complex, the rising demand for data is exacting growing social costs. Some of those problems are well known, such as the demographic skew in many facial recognition datasets toward White, male subjects — a bias passed on to the algorithms.

But there is a broader data crisis in machine learning. As machine learning datasets expand, they increasingly infringe on privacy by using images, text, or other material scraped without user consent; recycle toxic content; and are the source of other, more unpredictable biases and misjudgments.

More here.

Squid Game’s Capitalist Parables

E. Tammy Kim in The Nation:

Squid Game is not a subtle show, either in its politics or plot. Capitalism is bloody and mean and relentless; it yells. Each episode moves from one game to the next, in a series that, by the end, combined with some awkward English-language dialogue, feels hopelessly strained. But the show redeems itself with its memorable characters (all archetypal strugglers) and its bright, video-game-inspired design. The art director, Choi Kyoung-sun, said that she wanted to build a “storybook” world—a child’s late-capitalist hell—and she has done so brilliantly.

Squid Game is not a subtle show, either in its politics or plot. Capitalism is bloody and mean and relentless; it yells. Each episode moves from one game to the next, in a series that, by the end, combined with some awkward English-language dialogue, feels hopelessly strained. But the show redeems itself with its memorable characters (all archetypal strugglers) and its bright, video-game-inspired design. The art director, Choi Kyoung-sun, said that she wanted to build a “storybook” world—a child’s late-capitalist hell—and she has done so brilliantly.

More here.

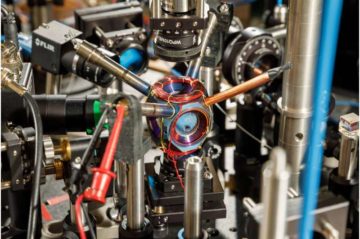

This device could usher in GPS-free navigation

From Phys.org:

Countless devices around the world use GPS for wayfinding. It’s possible because atomic clocks, which are known for extremely accurate timekeeping, hold the network of satellites perfectly in sync.

Countless devices around the world use GPS for wayfinding. It’s possible because atomic clocks, which are known for extremely accurate timekeeping, hold the network of satellites perfectly in sync.

But GPS signals can be jammed or spoofed, potentially disabling navigation systems on commercial and military vehicles alike, Schwindt said.

So instead of relying on satellites, Schwindt said future vehicles might keep track of their own position. They could do that with on-board devices as accurate as atomic clocks, but that measure acceleration and rotation by shining lasers into small clouds of rubidium gas like the one Sandia has contained.

More here. [Thanks to Georg Hofer.]

In Our Time: Iris Murdoch

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubNYTT5WGCw

Grouper: Shade

Daniel Bromfield at Pitchfork:

Liz Harris always seems to be telling us a secret. The catch—and the thing that makes her music as Grouper so fascinating—is we’re never sure what. Titles like “Thanksgiving Song” and “The Man Who Died in His Boat” hint that she’s letting us in on specific moments and memories, but the lyrics lean toward abstraction, and that’s when you can make them out from behind a thick wall of reverb. From 2014’s Ruins onward, Harris has scrubbed away much of the grit from her sound, and it’s been a thrill to watch her music hint at candor before ducking back into the shadows where it thrives. Shade takes this knife’s-edge balance between intimacy and inscrutability to the extreme.

Liz Harris always seems to be telling us a secret. The catch—and the thing that makes her music as Grouper so fascinating—is we’re never sure what. Titles like “Thanksgiving Song” and “The Man Who Died in His Boat” hint that she’s letting us in on specific moments and memories, but the lyrics lean toward abstraction, and that’s when you can make them out from behind a thick wall of reverb. From 2014’s Ruins onward, Harris has scrubbed away much of the grit from her sound, and it’s been a thrill to watch her music hint at candor before ducking back into the shadows where it thrives. Shade takes this knife’s-edge balance between intimacy and inscrutability to the extreme.

Many of Shade’s nine tracks feel like experiments in how much Harris can remove from her music while retaining its essential mystery. The album’s most notable development is to present her voice and acoustic guitar largely unadorned. The setting is so spare we can hear the buzz of the room and the squeak of her fingers on the frets.

more here.