https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twcL3ECF89Q

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twcL3ECF89Q

Casey Cep at The New Yorker:

No woman could get away with it. Murdering her children is all she would ever be known for—ask Medea. Yet Herakles, often called by his Roman name, Hercules, is known for everything else: slaying the man-eating birds of the Stymphalian marsh, the multiheaded Lernaean Hydra, and the Nemean lion, with its Kevlar-strength fur; capturing the wild Erymanthian boar, the golden-antlered deer of Artemis, and the Minotaur’s father; stealing the girdle of Hippolyta, the golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides, the flesh-eating mares of Diomedes, and the red cattle of the giant Geryon; mucking the Augean stables in a single day; and kidnapping the three-headed dog Cerberus from Hades.

No woman could get away with it. Murdering her children is all she would ever be known for—ask Medea. Yet Herakles, often called by his Roman name, Hercules, is known for everything else: slaying the man-eating birds of the Stymphalian marsh, the multiheaded Lernaean Hydra, and the Nemean lion, with its Kevlar-strength fur; capturing the wild Erymanthian boar, the golden-antlered deer of Artemis, and the Minotaur’s father; stealing the girdle of Hippolyta, the golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides, the flesh-eating mares of Diomedes, and the red cattle of the giant Geryon; mucking the Augean stables in a single day; and kidnapping the three-headed dog Cerberus from Hades.

Those dozen labors have inspired countless playwrights, poets, and philosophers throughout the centuries, not to mention Walt Disney Pictures. In the cartoon version of the tale, from 1997, Hercules’ hardscrabble climb from the lowly farms outside Thebes where he was raised to his rightful place atop Mt. Olympus beside Zeus—who, in the myth, fathered Herakles with a mortal, Alcmene, the wife of a Theban general, Amphitryon—seems like a mashup of “Survivor” and “American Idol.”

more here.

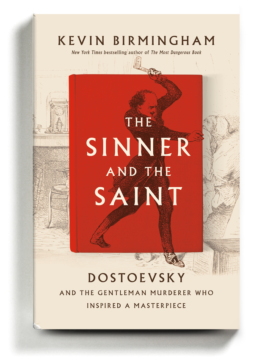

Oliver Ready at Literary Review:

There’s nothing wrong, of course, with taking one’s Crime and Punishment neat, without footnotes, introduction or weighty biography, sans everything except Dostoevsky’s incandescent text (as recast by your pick of fourteen translators). Countless readers, and all good formalists, have done just that, not least because the old translations tended to have no notes. Why interrupt the spell, the morbid giddiness that overcomes the trusting reader almost as strongly as it does Rodion Raskolnikov, in whose garret and mind we perch throughout the most searing pages of the novel? What’s more, this is a book that many devour when they are roughly the same age as Dostoevsky’s murderer (twenty-three), if not several years younger. Raskolnikov, as we first meet him, is imprisoned by his internal, ever ‘relatable’ struggle with social conventions and family pressures, and his story is in one shocking sense a universal metaphor: we all have our crimes to commit. Who has time for footnotes if your main concern is to determine whether you are with the ‘Lycurguses, Solons, Muhammads, Napoleons’, with those who have the right to transgress and trample over others, or whether you are merely a ‘quivering creature’ or, still worse, a bookish ‘aesthetic louse’?

There’s nothing wrong, of course, with taking one’s Crime and Punishment neat, without footnotes, introduction or weighty biography, sans everything except Dostoevsky’s incandescent text (as recast by your pick of fourteen translators). Countless readers, and all good formalists, have done just that, not least because the old translations tended to have no notes. Why interrupt the spell, the morbid giddiness that overcomes the trusting reader almost as strongly as it does Rodion Raskolnikov, in whose garret and mind we perch throughout the most searing pages of the novel? What’s more, this is a book that many devour when they are roughly the same age as Dostoevsky’s murderer (twenty-three), if not several years younger. Raskolnikov, as we first meet him, is imprisoned by his internal, ever ‘relatable’ struggle with social conventions and family pressures, and his story is in one shocking sense a universal metaphor: we all have our crimes to commit. Who has time for footnotes if your main concern is to determine whether you are with the ‘Lycurguses, Solons, Muhammads, Napoleons’, with those who have the right to transgress and trample over others, or whether you are merely a ‘quivering creature’ or, still worse, a bookish ‘aesthetic louse’?

more here.

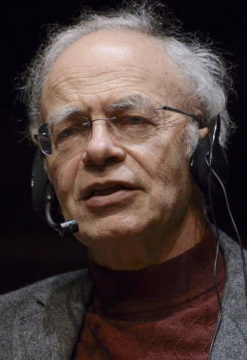

Yascha Mounk interviews Peter Singer at Persuasion (audio also available):

Yascha Mounk: What’s the case for being a utilitarian and seeing the world through utilitarian eyes?

Peter Singer: I think utilitarianism—far from being a kind of dry economic science or anything like that—is actually a reforming impulse. That goes back a long way before Jeremy Bentham, but was certainly made explicit by Bentham. Bentham and [later] utilitarians have been against slavery, they’ve been for women’s rights. They’ve been for the rights of gay people long before anybody else dared to even talk about that. They’ve been against cruelty to animals. They’ve been for prison reform. There’s a long list of things that utilitarians have been trying to reduce the amount of suffering in relation to and I’m very happy to be part of that tradition and to think of utilitarianism not merely as something for philosophers to talk about, but something that motivates people to act.

Peter Singer: I think utilitarianism—far from being a kind of dry economic science or anything like that—is actually a reforming impulse. That goes back a long way before Jeremy Bentham, but was certainly made explicit by Bentham. Bentham and [later] utilitarians have been against slavery, they’ve been for women’s rights. They’ve been for the rights of gay people long before anybody else dared to even talk about that. They’ve been against cruelty to animals. They’ve been for prison reform. There’s a long list of things that utilitarians have been trying to reduce the amount of suffering in relation to and I’m very happy to be part of that tradition and to think of utilitarianism not merely as something for philosophers to talk about, but something that motivates people to act.

More here.

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

As the holidays approach, we are being reminded of the fragility of the global supply chain. But at the same time, the supply chain itself is a truly impressive and fascinating structure, made as it is from multiple components that must work together in synchrony. From building an item in a factory and shipping it worldwide to transporting it locally, processing it in a distribution center, and finally delivering it to an address, the system is simultaneously awe-inspiring and deeply dehumanizing. I talk with Christopher Mims about how things are made, how they get to us, and what it all means for the present and future of our work and our lives.

As the holidays approach, we are being reminded of the fragility of the global supply chain. But at the same time, the supply chain itself is a truly impressive and fascinating structure, made as it is from multiple components that must work together in synchrony. From building an item in a factory and shipping it worldwide to transporting it locally, processing it in a distribution center, and finally delivering it to an address, the system is simultaneously awe-inspiring and deeply dehumanizing. I talk with Christopher Mims about how things are made, how they get to us, and what it all means for the present and future of our work and our lives.

More here.

Nate Sheff in Aeon:

Epistemology, the philosophical study of knowledge, belief and evidence, starts here, with our fallibility. And from this beginning, there are many paths for epistemology to take, and many sorts of questions to set us down these trails.

Epistemology, the philosophical study of knowledge, belief and evidence, starts here, with our fallibility. And from this beginning, there are many paths for epistemology to take, and many sorts of questions to set us down these trails.

For instance, we could continue by asking about the nature of thinking itself. Does thinking amount to nothing more than forming and reforming beliefs? Or is it something else entirely? Another option is to ask what counts as ‘success’ or ‘correctness’ in believing. This second path concerns what epistemologists call ‘justification’. Since true thoughts don’t come with a special glow announcing themselves as true, we can’t use truth as a marker for well-formed, worthwhile beliefs. Rather, we might look for something else to sort the good beliefs and opinions from the bad – something that justifies some beliefs rather than others, and that explains why some are credible and some aren’t.

Indeed, this is the big question for many epistemologists: what justification and credibility actually are.

More here.

Is it true you started weeping

when you came across that picture

of John Ashbery in Water Mill?

Yes well, I weep all the time,

not because I am sad but because

everything eventually meets

everything else. Isn’t it gratifying?

Anyway it wasn’t about John’s clever

eyebrows and I am having a perfectly good time.

On Sunday I saw a Japanese film about family, then

walked down Houston Street in search of something

left over.

Norma wanted to work, which disappointed me.

Come walk the streets with me, Norma!

Have those dirty martinis you like! Am I not shinier than your manuscripts?

At Milano’s, a group of Venezuelans watched the Super Bowl,

it didn’t seem to matter much. The man

next to me was a pilot, Monday he was on call for a flight to Ohio.

I’ve never been to Ohio, but I showed him a poem by Frank O’Hara

and showed the bartender too because I wanted to make him cry.

He was charming and took several

cigarette breaks. In the spring,

he’ll be playing Macbeth at a theater

right by my old apartment on Rivington Street.

Doesn’t it make you wild with joy? The clicks and entertainments?

I’m trying to explain about John Ashbery,

who gave a talk at NYU a few years ago

and I think shook my hand.

He wasn’t dashing anymore, and I won’t be either

one day. Other than that his face was the same,

clever and unyielding like a clean, steel hammer you can count on.

I was there with a friend I don’t speak to these days but I’m grateful for the occasion.

When Ashbery died, I was in Woodstock not too far away

writing my more laborious poems, fucking a twenty-two year old I liked

because he admired me.

I don’t need to explain myself, do I?

This is my youth, isn’t it?

I am filled with anxieties and I don’t want to spend my days fluffing my wings

like a sidewalk pigeon, waiting for crumbs.

At least the streets are warm for February.

If I get dressed and ready now I’ll still make it in time

to meet some sharp and begging stranger for a beer.

by Alex Sarrigeorgiou

from Bodega Magazine, July 2021

Colleen Walsh in The Harvard Gazette:

Marcus du Sautoy was around 13 when the exploits of a 19th-century German math genius changed his life. According to legend, the young Carl Friedrich Gauss was asked to calculate the sum of the numbers from one to 100, but instead of adding up the digits one by one, he realized 50 pairs of numbers (one plus 100, two plus 99, and so on) all equaled 101. So, he simply multiplied 50 times 101 and dropped the correct answer, 5,050, on his teacher’s desk.

Marcus du Sautoy was around 13 when the exploits of a 19th-century German math genius changed his life. According to legend, the young Carl Friedrich Gauss was asked to calculate the sum of the numbers from one to 100, but instead of adding up the digits one by one, he realized 50 pairs of numbers (one plus 100, two plus 99, and so on) all equaled 101. So, he simply multiplied 50 times 101 and dropped the correct answer, 5,050, on his teacher’s desk.

“When I heard this story,” said du Sautoy, “I thought, ‘Wow, that’s the subject I want to dedicate myself to.’”

Through teaching, TV appearances, and bestsellers, the Oxford professor of mathematics has done exactly that, bringing math and science to the masses. In an online Harvard Science Book Talk on Monday, du Sautoy, clad in a black shirt covered with white numbers, discussed his new book, “Thinking Better: The Art of the Shortcut in Math and Life,” with Melissa Franklin, Harvard’s Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics. The art of the shortcut isn’t about cutting corners, he emphasized. Instead, it’s about thinking cleverly about a problem to avoid the “boring work,” so you can “get to the work you want to do.” The book, he said, is a “celebration of mathematics,” as well as “a kind of interesting exploration of the shortcut beyond my world of maths.”

And many worlds there are. While researching his work, he interviewed experts in a range of fields. From an accomplished cellist he learned that scales are a kind of pattern, or shortcut, enabling musicians to play without analyzing each note. But he also learned that there’s no getting around the muscle memory required to master an instrument. “If you have to change the body physically in some way,” he said, “then it’s very hard to actually shortcut that.”

A mountaineer told du Sautoy that shortcuts occasionally come in handy, recalling a time when he triggered a small avalanche so he could quickly slip along the snow to avoid getting stuck on a summit at night. But more often, the climber took the long way up and down because he relished the views and “being in the moment.” The same is true for those who want to inhabit a piece of music, said the author. A song clip won’t immerse the listener in the work the way a full recording does. Conversely, a movie trailer might be “a useful shortcut to get a quick feel for what the film might be like,” he said.

More here.

Steffan Messenger in BBC:

Prof Crowther, who grew up in Prestatyn, Flintshire, is a professor of ecosystem ecology at ETH Zurich University in Switzerland and also chairs an advisory board for the United Nations on nature restoration. He warned blanket planting of trees was “hugely threatening”. “This is not about offsetting your guilt, that would be an absolutely devastating step for climate change,” he said. Speaking at COP26 in Glasgow, Prof Crowther said the loss of biodiversity was arguably a bigger threat to the planet than climate change. “If we save the climate but we lose nature that’s still an unliveable planet,” said the scientist, who studied at Cardiff University. He said it had become increasingly clear that efforts to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees depended on doing much more to restore the natural world.

Prof Crowther, who grew up in Prestatyn, Flintshire, is a professor of ecosystem ecology at ETH Zurich University in Switzerland and also chairs an advisory board for the United Nations on nature restoration. He warned blanket planting of trees was “hugely threatening”. “This is not about offsetting your guilt, that would be an absolutely devastating step for climate change,” he said. Speaking at COP26 in Glasgow, Prof Crowther said the loss of biodiversity was arguably a bigger threat to the planet than climate change. “If we save the climate but we lose nature that’s still an unliveable planet,” said the scientist, who studied at Cardiff University. He said it had become increasingly clear that efforts to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees depended on doing much more to restore the natural world.

Prof Crowther’s post-doctoral research made headlines when it estimated there were approximately 3.04 trillion trees on Earth – 46% fewer than at the onset of agriculture about 12,000 years ago. It sparked the Trillion Tree campaign which is being “very prominently discussed” at COP26. Although Prof Crowther emphasised it was important people “understand that we’re not just talking about planting trees”. “In the vast majority of cases, what we’re really going to be doing is protecting large areas of land, we need to protect a third of the land surface so that nature can recover and naturally grow,” he added.

More here.

Lynne Murphy in the TLS:

Until recently, Fran Lebowitz was not well known in Britain. The release this year of Martin Scorsese’s Netflix series Pretend It’s a City, however, has made her something of a household name here. A veritable Franbase has now formed in the UK, giving rise to online appearances, a tour scheduled for next year and the first publication in this country of The Fran Lebowitz Reader (which was originally published in the United States in 1994). The Lebowitz on the dust jacket is one fans of the series will recognize: the seasoned New Yorker with gorgeous overcoat, horn-rimmed sunglasses and cigarette, as famous for her writer’s block as for her wit. Between the covers, we meet the artist as a young woman. The Reader reproduces her only two essay collections: Metropolitan Life (1978) and Social Studies (1981), which in turn reproduce her magazine pieces of that era.

Until recently, Fran Lebowitz was not well known in Britain. The release this year of Martin Scorsese’s Netflix series Pretend It’s a City, however, has made her something of a household name here. A veritable Franbase has now formed in the UK, giving rise to online appearances, a tour scheduled for next year and the first publication in this country of The Fran Lebowitz Reader (which was originally published in the United States in 1994). The Lebowitz on the dust jacket is one fans of the series will recognize: the seasoned New Yorker with gorgeous overcoat, horn-rimmed sunglasses and cigarette, as famous for her writer’s block as for her wit. Between the covers, we meet the artist as a young woman. The Reader reproduces her only two essay collections: Metropolitan Life (1978) and Social Studies (1981), which in turn reproduce her magazine pieces of that era.

In the 1980s, those two books meant a great deal to young American women like me; they survived the subsequent drastic book culls necessitated by my three transatlantic relocations. Impossibly cool, cosmopolitan, smart, self-confident and hilarious, Lebowitz was (and is) the kind of woman we wanted to be, were afraid to be, and (let’s be honest) didn’t have the talent to be.

More here.

Bob Berwyn in Undark:

It’s been more than 30 years since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change first warned the world that greenhouse gases were dangerously warming the global climate. Decades of United Nations climate negotiations followed, culminating in the 2015 Paris agreement. Yet, in that time, humans have pumped more carbon dioxide into the air than in the preceding 240 years.

It’s been more than 30 years since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change first warned the world that greenhouse gases were dangerously warming the global climate. Decades of United Nations climate negotiations followed, culminating in the 2015 Paris agreement. Yet, in that time, humans have pumped more carbon dioxide into the air than in the preceding 240 years.

Since that first IPCC report in 1990, emissions have increased 60 percent and the average global temperature has climbed about 0.75 degrees Celsius, contributing to rapid increases in deadly heat waves, tropical storms, droughts, and sea level rise on every continent. According to the United Nations Emissions Gap report released Oct. 27, the most recently updated climate pledges shave about 7.5 percent off 2030 emissions, while a reduction of 55 percent is needed to meet the target of the Paris agreement. That puts Earth on track to heat 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100, a dangerous amount of warming well beyond the Paris agreement target of 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The reasons emissions and temperatures have continued to increase, even as their impacts and global efforts to rein them in have grown, are complex, and the answers depend on whom you ask. But some recent climate studies suggest a common thread in the hows and whys: the continued failure to put environmental justice at the center of climate negotiations.

More here.

David Marchese in the New York Times:

With the publication in the United States of his best-selling “Sapiens” in 2015, the Israeli historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari arrived at the top rank of public intellectuals, a position he consolidated with “Homo Deus” (2017) and “21 Lessons for the 21st Century” (2018). Harari’s key theme is the idea that human society has largely been driven by our species’s capacity to believe in what he calls fictions: those things whose power is derived from their existence in our collective imaginations, whether they be gods or nations; our belief in them allows us to cooperate on a societal scale. The broad sweep of Harari’s writing, which encompasses the prehistoric past and a dark far-off future, has turned him into a bit of a walking inkblot test. “The general misunderstandings of me,” says Harari, 45, co-author of the recently published “Sapiens: A Graphic History, Volume 2” (the latest in a series of graphic-novel adaptations of his work), “are that I’m the prophet of doom and then there’s this opposite view that I think everything is wonderful.” Both, of course, might be true. “Once the books are out, the ideas are out of your hands,” he says.

With the publication in the United States of his best-selling “Sapiens” in 2015, the Israeli historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari arrived at the top rank of public intellectuals, a position he consolidated with “Homo Deus” (2017) and “21 Lessons for the 21st Century” (2018). Harari’s key theme is the idea that human society has largely been driven by our species’s capacity to believe in what he calls fictions: those things whose power is derived from their existence in our collective imaginations, whether they be gods or nations; our belief in them allows us to cooperate on a societal scale. The broad sweep of Harari’s writing, which encompasses the prehistoric past and a dark far-off future, has turned him into a bit of a walking inkblot test. “The general misunderstandings of me,” says Harari, 45, co-author of the recently published “Sapiens: A Graphic History, Volume 2” (the latest in a series of graphic-novel adaptations of his work), “are that I’m the prophet of doom and then there’s this opposite view that I think everything is wonderful.” Both, of course, might be true. “Once the books are out, the ideas are out of your hands,” he says.

Some of the big ideas about humanity that you’ve helped popularize — that fictions or social constructs have political power or that Homo sapiens might be moving toward technologically driven obsolescence — have been around in various forms since way before you wrote about them. So what do you think it is about how you convey them that’s been so compelling?

One hypothesis is that I’m coming from the discipline of history, and many of the recent attempts to create this kind of big synthesis were from biology and evolution or from economics and social sciences. In recent decades the humanities kind of gave up, and it became almost taboo to try to create grand narratives. But the humanities’ perspective is essential.

More here.

Lorraine Boissoneault in Smithsonian:

The pain struck suddenly in Venice.

The pain struck suddenly in Venice.

Writing to her doctor brother-in-law in 1839, famed British writer Harriet Martineau complained of the “inability to stand or walk, aching and weariness of the back, extending down the legs to the heels” and “tenderness and pain, on pressure, in the left groin, extending by the hip to the back.” She’d been traveling through Europe with a group of friends for several months, but now it seemed the completion of her adventures would have to be put on hold.

Within weeks, Martineau was back in England, where she was diagnosed with a retroverted uterus and polypus tumors: two vaguely defined conditions without a cure. (These ailments would likely be diagnosed differently today, but modern scholars often shy away from definitively diagnosing historical figures due to the difficulty of doing so with limited information.) As for treatments, the most Martineau could hope for was iodide of iron for “purifying the blood,” morphine for the pain and the general cure-all treatment of bloodletting. Resigning herself to an illness of unknown duration, Martineau moved to Tynemouth, a town on the northeastern coast of England, and hired nurses and servants to care for her in this new sickroom. She would remain there for the next five years, largely unable to leave due to the pain of walking.

More here.

Lina Zeldovich in Nautilus:

One day in 2010, when oncologist Paul Muizelaar operated on a patient with glioblastoma—a brain tumor infamous for its deathly toll—he did something shocking. First, he cut the skull open and carved out as much of the tumor as he could. But before he replaced the piece of skull to close the wound, he soaked it in a solution containing Enterobacter aerogenes,1 bacteria found in feces. For the next month, the patient lay in a coma in an intensive care unit battling the bacteria he was infected with—and then one day a scan of his brain no longer showed the distinctive signature of glioblastoma. Instead, it showed an abscess, which, given the situation, Muizelaar deemed a positive development. “A brain abscess can be treated, a glioblastoma cannot,” he later told the New Yorker. Trying it, he thought, was worth the chance. He had done this only as a means of last resort in a couple of hopeless cases—but ultimately, his patients still passed away, which led to a scandal that forced him to retire.

One day in 2010, when oncologist Paul Muizelaar operated on a patient with glioblastoma—a brain tumor infamous for its deathly toll—he did something shocking. First, he cut the skull open and carved out as much of the tumor as he could. But before he replaced the piece of skull to close the wound, he soaked it in a solution containing Enterobacter aerogenes,1 bacteria found in feces. For the next month, the patient lay in a coma in an intensive care unit battling the bacteria he was infected with—and then one day a scan of his brain no longer showed the distinctive signature of glioblastoma. Instead, it showed an abscess, which, given the situation, Muizelaar deemed a positive development. “A brain abscess can be treated, a glioblastoma cannot,” he later told the New Yorker. Trying it, he thought, was worth the chance. He had done this only as a means of last resort in a couple of hopeless cases—but ultimately, his patients still passed away, which led to a scandal that forced him to retire.

Muizelaar’s approach may sound beyond outrageous, but it wasn’t entirely crazy. For over 200 years medics have known that infections, particularly those accompanied by fevers, can have a strange and shocking effect on cancers: Sometimes they wipe the tumors out. The empirical evidence for these hard-to-believe cures has been documented in medical literature, dating back to the 1700s. In the 19th century, some doctors tried treating cancer patients by deliberately infecting them with live bacterial pathogens. Sometimes it worked, sometimes the patients died. Injecting people with dead bacteria worked better and, in fact, saved lives, at least in some cancers. The problem was that it didn’t work consistently and repeatedly so it never became an established treatment paradigm. Moreover, no one could explain how the method worked and what it did. Doctors speculated that infections somehow revved up the body’s defenses, but even in the early 20th century, they had no means of elucidating the mysterious force that devoured the tumor.

More here.

Erick Neher at The Hudson Review:

“I’m a storyteller” is a common self-description for virtually everyone in the film industry these days, from directors and scenarists to publicists and marketers. The phrase is a quintessential humble-brag. It carries a sense of modesty: “I may have a profoundly intricate knowledge of my craft, but at heart I’m no different from the people spinning a good yarn for their kids.” But it also holds a whiff of epic continuity, placing the speaker in a line that reaches back to Homer, and beyond that to the nameless bards who first narrativized our species into civilization. All to say: the phrase has passed through ubiquity to become an increasingly mocked cliché. Which is why it was so refreshing to hear the French director Leos Carax say in a recent interview with the New York Times, “I’m not a storyteller.” He’s right. He’s a poet, a provocateur, an artist—but anyone attending a Carax movie expecting narrative coherence, character logic, or shapely story arcs will be sadly disappointed. “I try to compose emotional scores, like movements that flow into minor and major keys,” Carax continued. And indeed his films, including his latest, Annette, have more in common with modern music than they do with theater or literature.

“I’m a storyteller” is a common self-description for virtually everyone in the film industry these days, from directors and scenarists to publicists and marketers. The phrase is a quintessential humble-brag. It carries a sense of modesty: “I may have a profoundly intricate knowledge of my craft, but at heart I’m no different from the people spinning a good yarn for their kids.” But it also holds a whiff of epic continuity, placing the speaker in a line that reaches back to Homer, and beyond that to the nameless bards who first narrativized our species into civilization. All to say: the phrase has passed through ubiquity to become an increasingly mocked cliché. Which is why it was so refreshing to hear the French director Leos Carax say in a recent interview with the New York Times, “I’m not a storyteller.” He’s right. He’s a poet, a provocateur, an artist—but anyone attending a Carax movie expecting narrative coherence, character logic, or shapely story arcs will be sadly disappointed. “I try to compose emotional scores, like movements that flow into minor and major keys,” Carax continued. And indeed his films, including his latest, Annette, have more in common with modern music than they do with theater or literature.

more here.