Ayad Akhtar in The Atlantic:

Something unnatural is afoot. Our affinities are increasingly no longer our own, but rather are selected for us for the purpose of automated economic gain. The automation of our cognition and the predictive power of technology to monetize our behavior, indeed our very thinking, is transforming not only our societies and discourse with one another, but also our very neurochemistry. It is a late chapter of a larger story, about the deepening incursion of mercantile thinking into the groundwater of our philosophical ideals. This technology is no longer just shaping the world around us, but actively remaking us from within.

Something unnatural is afoot. Our affinities are increasingly no longer our own, but rather are selected for us for the purpose of automated economic gain. The automation of our cognition and the predictive power of technology to monetize our behavior, indeed our very thinking, is transforming not only our societies and discourse with one another, but also our very neurochemistry. It is a late chapter of a larger story, about the deepening incursion of mercantile thinking into the groundwater of our philosophical ideals. This technology is no longer just shaping the world around us, but actively remaking us from within.

That we are subject to the dominion of endless digital surveillance is not news. And yet, the sheer scale of the domination continues to defy our imaginative embrace. Virtually everything we do, everything we are, is transmuted now into digital information. Our movements in space, our breathing at night, our expenditures and viewing habits, our internet searches, our conversations in the kitchen and in the bedroom—all of it observed by no one in particular, all of it reduced to data parsed for the patterns that will predict our purchases.

But the model isn’t simply predictive. It influences us. Daniel Kahneman’s seminal work in behavioral psychology has demonstrated the effectiveness of unconscious priming. Whether or not you are aware that you’ve seen a word, that word affects your decision making. This is the reason the technology works so well. The regime of screens that now comprises much of the surface area of our daily cognition operates as a delivery system for unconscious priming. Otherwise known as advertising technology, this is the system behind the website banners, the promotions tab in your Gmail, the Instagram Story you swipe through, the brand names glanced at in email headings, the words and images insinuated between posts in feeds of various sorts. The ads we don’t particularly pay attention to shape us more than we know, part of the array of the platforms’ sensory stimuli, all working in concert to adhere us more completely.

More here.

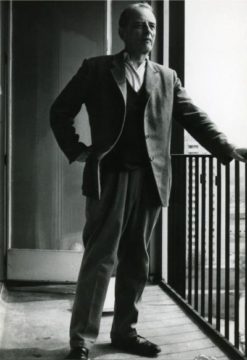

To be a literary biographer is to court the extravagant ridicule of the very people you write about. For all of the salutary services a writer’s biography can offer — the tracing of the life, the contextualizing of the work, the resuscitation of a reputation and the deliverance from neglect — the biographer has been derided as a “post-mortem exploiter” (Henry James) and a “professional burglar” (Janet Malcolm).

To be a literary biographer is to court the extravagant ridicule of the very people you write about. For all of the salutary services a writer’s biography can offer — the tracing of the life, the contextualizing of the work, the resuscitation of a reputation and the deliverance from neglect — the biographer has been derided as a “post-mortem exploiter” (Henry James) and a “professional burglar” (Janet Malcolm). The standard history of humanity goes something like this. Roughly 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens first evolved somewhere on the African continent. Over the next 100,000 to 150,000 years, this sturdy, adaptable species moved into new regions, first on its home continent and then into other parts of the globe. These early humans shaped flint and other stones into cutting blades of increasing complexity and used their tools to hunt the mega-fauna of the Pleistocene era. Sometimes, they immortalized these hunts—carved on rock faces or painted in glorious murals across the walls and ceilings of caves in places like Sulawesi, Chauvet, and Lascaux.

The standard history of humanity goes something like this. Roughly 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens first evolved somewhere on the African continent. Over the next 100,000 to 150,000 years, this sturdy, adaptable species moved into new regions, first on its home continent and then into other parts of the globe. These early humans shaped flint and other stones into cutting blades of increasing complexity and used their tools to hunt the mega-fauna of the Pleistocene era. Sometimes, they immortalized these hunts—carved on rock faces or painted in glorious murals across the walls and ceilings of caves in places like Sulawesi, Chauvet, and Lascaux. It’s easy to mock the Corporation Formerly Known As Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement that Facebook would

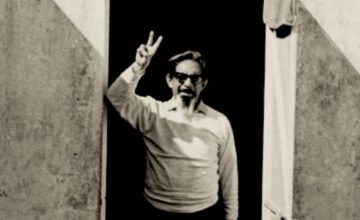

It’s easy to mock the Corporation Formerly Known As Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement that Facebook would  A LITTLE OVER halfway through his 1943 novel El luto humano (Human Mourning), the Mexican writer José Revueltas inserts himself as a character so unobtrusively that it’s easy to miss. A government go-between, when hiring an assassin to kill the leader of an agricultural strike, complains, “First there was the agitation sown by José de Arcos, Revueltas, Salazar, García, and the other Communists. […] And now all over again…” It’s a sly wink at the fact that the novel’s scenario overlaps with the author’s life; it also foreshadows the way that Revueltas’s place in Mexican letters today is inextricably entwined with his dramatic biography.

A LITTLE OVER halfway through his 1943 novel El luto humano (Human Mourning), the Mexican writer José Revueltas inserts himself as a character so unobtrusively that it’s easy to miss. A government go-between, when hiring an assassin to kill the leader of an agricultural strike, complains, “First there was the agitation sown by José de Arcos, Revueltas, Salazar, García, and the other Communists. […] And now all over again…” It’s a sly wink at the fact that the novel’s scenario overlaps with the author’s life; it also foreshadows the way that Revueltas’s place in Mexican letters today is inextricably entwined with his dramatic biography. The instant recognisability of Magritte’s work has its roots not in his training at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918 but in his postwar work as a draughtsman in the city from 1922 to 1926. During this time he made artworks for advertising companies and designed wallpaper and posters. The skills garnered from the first two of these are immediately evident in Golconda, now in the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. The bowler-hatted men, part Thomson and Thompson, part Gilbert and George, are as obviously Magritte’s logo as the part-eaten apple is that of a certain American computer giant. His eye for pattern was also acute. Golconda would make lovely wallpaper, and no doubt has.

The instant recognisability of Magritte’s work has its roots not in his training at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918 but in his postwar work as a draughtsman in the city from 1922 to 1926. During this time he made artworks for advertising companies and designed wallpaper and posters. The skills garnered from the first two of these are immediately evident in Golconda, now in the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. The bowler-hatted men, part Thomson and Thompson, part Gilbert and George, are as obviously Magritte’s logo as the part-eaten apple is that of a certain American computer giant. His eye for pattern was also acute. Golconda would make lovely wallpaper, and no doubt has. Depending on the outcome of social conflicts, ants of the species Harpegnathos saltator do something unusual: they can switch from a worker to a queen-like status known as gamergate. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Cell on November 4th have made the surprising discovery that a single protein, called Kr-h1 (Krüppel homolog 1), responds to socially regulated hormones to orchestrate this complex social transition.

Depending on the outcome of social conflicts, ants of the species Harpegnathos saltator do something unusual: they can switch from a worker to a queen-like status known as gamergate. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Cell on November 4th have made the surprising discovery that a single protein, called Kr-h1 (Krüppel homolog 1), responds to socially regulated hormones to orchestrate this complex social transition. “Ever since I have been at court,” exclaimed the vidame, “the queen has always treated me with much distinction and amiability, and I have reason to believe she has had a kindly feeling for me. Yet there was nothing marked about it, and I had never dreamed of other feelings toward me than those of respect. I was even much in love with Madame de Themines. The sight of her is enough to prove that a man can have a great deal of love for her when she loves him—and she loved me.

“Ever since I have been at court,” exclaimed the vidame, “the queen has always treated me with much distinction and amiability, and I have reason to believe she has had a kindly feeling for me. Yet there was nothing marked about it, and I had never dreamed of other feelings toward me than those of respect. I was even much in love with Madame de Themines. The sight of her is enough to prove that a man can have a great deal of love for her when she loves him—and she loved me. In 1966, I was a junior at St. Louis’s Kirkwood High. After the teachers let us monkeys out at 2:50, I lazed about, often trekking to a friend’s home to talk antiwar politics or Salinger stories. I was a serious kid, some days lying on one of the twin beds in Ken Klotz’s room (his unlucky brother off in Vietnam) where we were hypnotized by Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and the literary dazzle of “Visions of Johanna”: “The ghost of electricity howls from the bones of her face.” But then some days I needed a break.

In 1966, I was a junior at St. Louis’s Kirkwood High. After the teachers let us monkeys out at 2:50, I lazed about, often trekking to a friend’s home to talk antiwar politics or Salinger stories. I was a serious kid, some days lying on one of the twin beds in Ken Klotz’s room (his unlucky brother off in Vietnam) where we were hypnotized by Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and the literary dazzle of “Visions of Johanna”: “The ghost of electricity howls from the bones of her face.” But then some days I needed a break. But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments.

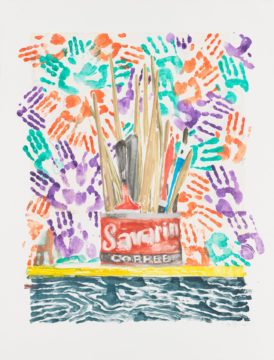

But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments. His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.”

His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.” For months, during the main

For months, during the main  It’s been more than 50 years since

It’s been more than 50 years since