Brian Callaci in The Boston Review:

Brian Callaci in The Boston Review:

A little less than a decade ago, after spending several years as a union staffer helping workers organize in low-wage industries, I was assigned to conduct research in support of fast food workers on strike for a $15 minimum wage and a union. It was exciting; workers were making bold demands on some of the most powerful corporations in the country, including a wage increase to double the current level of the Federal minimum wage. Too bold, in fact, for many. Democratic policymakers balked at $15. And with rare exceptions, the entire academic economics profession was opposed. Economists argued that if we forced employers to pay higher wages, they would simply hire fewer workers. A famous liberal economist even wrote a New York Times op-ed opposing $15. However, the Fight for $15 largely sidestepped the debates, so important to economists, about whether higher minimum wages would result in zero or nonzero job loss. Instead, it articulated a social vision of worker rights: workers had the right to the dignity of a living wage—their living in poverty was intolerable in a rich society.

Then a funny thing happened. Ignoring the experts, cities started passing $15 hourly minimum wage ordinances, and the economic sky didn’t fall. Unemployment didn’t skyrocket, or even rise perceptibly. The economists were wrong. Intellectually honest if initially mistaken, economists looked for theories that would better reflect reality, and a previously out-of-fashion theory known as “monopsony” became the new reigning conventional wisdom.

More here.

Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka:

Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka: The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on

The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on  On a May evening in 1959, C.P. Snow, a popular novelist and former research scientist, gave a lecture before a gathering of dons and students at the University of Cambridge, his alma mater. He called his talk “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.” Snow declared that a gulf of mutual incomprehension divided literary intellectuals and scientists.

On a May evening in 1959, C.P. Snow, a popular novelist and former research scientist, gave a lecture before a gathering of dons and students at the University of Cambridge, his alma mater. He called his talk “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.” Snow declared that a gulf of mutual incomprehension divided literary intellectuals and scientists. Several years ago, I met Francis Bacon’s cleaning lady. Bacon’s amanuensis, the art critic David Sylvester, referred me to her, as he had her to Bacon. Jean Ward, who had her grey hair swept back into a thin ponytail like a pirate’s, welcomed me to her flat on a housing estate in Tooting Beck, South London. In a raspy voice she told me about her decade working for the painter whose legendarily messy studio—layer upon layer of dust, paint, discarded imagery, champagne bottles, and other detritus—would not have provided her much of a recommendation for future jobs.

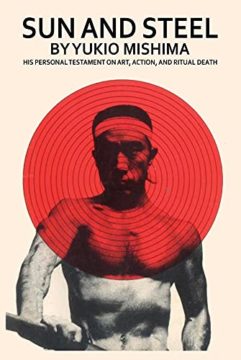

Several years ago, I met Francis Bacon’s cleaning lady. Bacon’s amanuensis, the art critic David Sylvester, referred me to her, as he had her to Bacon. Jean Ward, who had her grey hair swept back into a thin ponytail like a pirate’s, welcomed me to her flat on a housing estate in Tooting Beck, South London. In a raspy voice she told me about her decade working for the painter whose legendarily messy studio—layer upon layer of dust, paint, discarded imagery, champagne bottles, and other detritus—would not have provided her much of a recommendation for future jobs. He poses on the cover of my old Grove Press edition in the aspect of a warrior, stripped to the waist, forehead bound in a hachimaki, looking out from under heavy brows. His shadowed gaze is intent, unnerving. His left cheekbone and the strong bridge of his nose catch the light. (A humanizing touch: his ears stick out slightly too far.) In a suit he might seem ordinary, at best of average build, but shirtless he is a panther ready to spring. His forearms are unusually furry for a Japanese man, his concave stomach bifurcated by a line of black hair. His triceps resemble warm marble. Superimposed on this fierce portrait are the concentric rings of a red target, as though Mishima were about to be feathered with arrows like St. Sebastian—a picture of whose “white and matchless nudity” moves the frail narrator of Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask to his first ejaculation. In the center of this target, his grim mouth forms the bull’s-eye; the outer rings drape his shoulders and pectoral muscles like a mantle of blood. His right hand is drawing out of its sheath, upward into the frame, the naked blade of a samurai sword.

He poses on the cover of my old Grove Press edition in the aspect of a warrior, stripped to the waist, forehead bound in a hachimaki, looking out from under heavy brows. His shadowed gaze is intent, unnerving. His left cheekbone and the strong bridge of his nose catch the light. (A humanizing touch: his ears stick out slightly too far.) In a suit he might seem ordinary, at best of average build, but shirtless he is a panther ready to spring. His forearms are unusually furry for a Japanese man, his concave stomach bifurcated by a line of black hair. His triceps resemble warm marble. Superimposed on this fierce portrait are the concentric rings of a red target, as though Mishima were about to be feathered with arrows like St. Sebastian—a picture of whose “white and matchless nudity” moves the frail narrator of Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask to his first ejaculation. In the center of this target, his grim mouth forms the bull’s-eye; the outer rings drape his shoulders and pectoral muscles like a mantle of blood. His right hand is drawing out of its sheath, upward into the frame, the naked blade of a samurai sword. A blurb on the cover of my copy of Lolita calls the novel “the only convincing love story of our century.”

A blurb on the cover of my copy of Lolita calls the novel “the only convincing love story of our century.” Variants in

Variants in The Biden administration’s mantra for the Middle East is simple: “end the ‘forever wars.’” The White House is preoccupied with managing the challenge posed by China and aims to disentangle the United States from the Middle East’s seemingly endless and unwinnable conflicts. But the United States’ disengagement threatens to leave a political vacuum that will be filled by sectarian rivalries, paving the way for a more violent and unstable region.

The Biden administration’s mantra for the Middle East is simple: “end the ‘forever wars.’” The White House is preoccupied with managing the challenge posed by China and aims to disentangle the United States from the Middle East’s seemingly endless and unwinnable conflicts. But the United States’ disengagement threatens to leave a political vacuum that will be filled by sectarian rivalries, paving the way for a more violent and unstable region. On August 1 the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), a coalition of over sixty organizations, rolled out “

On August 1 the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), a coalition of over sixty organizations, rolled out “

Daniel Borzutzky’s poetry is not an easy, elegant read: trauma, prisons, torture, murders, and arresting phrases like “rotten carcass economy” and “the blankest of times” recur ad nauseam. To read Borzutzky is, in other words, to reckon with the “grotesque.”

Daniel Borzutzky’s poetry is not an easy, elegant read: trauma, prisons, torture, murders, and arresting phrases like “rotten carcass economy” and “the blankest of times” recur ad nauseam. To read Borzutzky is, in other words, to reckon with the “grotesque.” Quantum mechanics is nearly one hundred years old, and yet the challenge it presents to the imagination is so great that scientists are still coming to terms with some of its most basic implications. Here I will describe some theoretical insights and recent experimental results that are leading physicists to revise and expand their ideas about what quantum-mechanical particles are and how they behave. These new ideas are centered around a topic traditionally known as quantum statistics. The name is misleading: the basic physical phenomena do not involve statistics in the usual sense. A better title might have been the quantum mechanics of identity, but the new developments make that name obsolete too. A more accurate description would be the quantum mechanics of world-line topology. Since that is quite a mouthful, most researchers now simply refer to anyon physics.

Quantum mechanics is nearly one hundred years old, and yet the challenge it presents to the imagination is so great that scientists are still coming to terms with some of its most basic implications. Here I will describe some theoretical insights and recent experimental results that are leading physicists to revise and expand their ideas about what quantum-mechanical particles are and how they behave. These new ideas are centered around a topic traditionally known as quantum statistics. The name is misleading: the basic physical phenomena do not involve statistics in the usual sense. A better title might have been the quantum mechanics of identity, but the new developments make that name obsolete too. A more accurate description would be the quantum mechanics of world-line topology. Since that is quite a mouthful, most researchers now simply refer to anyon physics. Last week, in its

Last week, in its