Category: Recommended Reading

Wednesday Poem

Trio of Mortality

Phenotyping Tears

Today a man I hardly knew

Died peacefully while morphine dripped in

Lungs no longer wheezing wet sounding symphonies

An aura of quiet around him

His daughter is in the corner

Sniffling softly

Her tears are of understanding

The man in the next bed snored gently

Unaware, innocent

Outside,

In the hall

Life went on as usual

That moment,

That peaceful room

With the sniffling and the snoring

Was gone

Tears threaten to spill in

Tears of fate and

Embarrassed vulnerability

Walking home,

Darkness presents itself earlier and earlier

Cold blurs my eyes

Faces moving past are mere figures

Tears of winter

Read more »

Do Birds Have Language?

Betsy Mason in Smithsonian:

In our quest to find what makes humans unique, we often compare ourselves with our closest relatives: the great apes. But when it comes to understanding the quintessentially human capacity for language, scientists are finding that the most tantalizing clues lay farther afield.

In our quest to find what makes humans unique, we often compare ourselves with our closest relatives: the great apes. But when it comes to understanding the quintessentially human capacity for language, scientists are finding that the most tantalizing clues lay farther afield.

Human language is made possible by an impressive aptitude for vocal learning. Infants hear sounds and words, form memories of them, and later try to produce those sounds, improving as they grow up. Most animals cannot learn to imitate sounds at all. Though nonhuman primates can learn how to use innate vocalizations in new ways, they don’t show a similar ability to learn new calls. Interestingly, a small number of more distant mammal species, including dolphins and bats, do have this capacity. But among the scattering of nonhuman vocal learners across the branches of the bush of life, the most impressive are birds — hands (wings?) down.

Parrots, songbirds and hummingbirds all learn new vocalizations. The calls and songs of some species in these groups appear to have even more in common with human language, such as conveying information intentionally and using simple forms of some of the elements of human language such as phonology, semantics and syntax. And the similarities run deeper, including analogous brain structures that are not shared by species without vocal learning.

More here.

Anaesthesia: A Very Short Introduction

Aidan O’Donnell in Delancey Place:

“Cocaine is an alkaloid found in the leaves of the coca plant, Erythroxylum coca, which is native to South America. For centuries, the leaves have been chewed by South American people as a mild stimulant and appetite suppressant. Coca was brought back to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century. Cocaine itself was first isolated by Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855, and an improved purification process was developed by Albert Niemann in 1860. Later, it came to be incorporated into tonic drinks, such as Coca-Cola in 1866, and was available over the counter at Harrods in London until as late as 1916.

“Cocaine is an alkaloid found in the leaves of the coca plant, Erythroxylum coca, which is native to South America. For centuries, the leaves have been chewed by South American people as a mild stimulant and appetite suppressant. Coca was brought back to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century. Cocaine itself was first isolated by Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855, and an improved purification process was developed by Albert Niemann in 1860. Later, it came to be incorporated into tonic drinks, such as Coca-Cola in 1866, and was available over the counter at Harrods in London until as late as 1916.

“In 1884, a Viennese ophthalmologist called Karl Koller, an associate of Sigmund Freud, noted that drops of cocaine solution introduced into the eye produced local anaesthesia sufficient for the patient to tolerate eye surgery. The following year, William Halsted and Richard Hall in New York experimented with injecting cocaine around peripheral nerves, to cause numbness. As a result of their experiments on themselves, Halsted and Hall became addicted to cocaine.

More here.

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

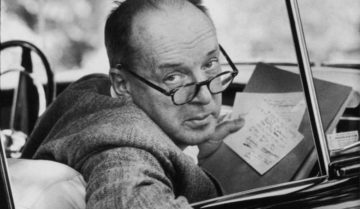

On the Not-So-Unlikely Friendship Between Vladimir Nabokov and William F. Buckley, Jr.

Sarah Weinman in Literary Hub:

In 1999, Nina Khrushcheva met William F. Buckley at the offices of National Review. Then a fellow at the New School’s World Policy Institute (and now a professor of international affairs at the university) Khrushcheva had much to discuss with Buckley, whom she’d first met a few months earlier at an event commemorating the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Buckley had been a panelist along with her uncle Sergey, son of the Cold War-era Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, one of Buckley’s sworn enemies in his, and the conservative movement’s, ferocious fight against Communism.

In 1999, Nina Khrushcheva met William F. Buckley at the offices of National Review. Then a fellow at the New School’s World Policy Institute (and now a professor of international affairs at the university) Khrushcheva had much to discuss with Buckley, whom she’d first met a few months earlier at an event commemorating the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Buckley had been a panelist along with her uncle Sergey, son of the Cold War-era Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, one of Buckley’s sworn enemies in his, and the conservative movement’s, ferocious fight against Communism.

National Review had gone so far to create a “Khrushchev Not Welcome Here” bumper sticker in 1959, in advance of the premier’s visit to the United States at President Eisenhower’s invitation. The “Kitchen Debates” with then-Vice President Richard Nixon did not alleviate any of Buckley’s concerns about the Communist threat. Forty years later, it all seemed rather ironic to Khrushcheva; her uncle had been an American resident since 1991. And she owned, and displayed, one of the bumper stickers in her own Upper West Side apartment.

More here.

J. Arvid Ågren’s “The Gene’s-Eye View of Evolution”

Daniel James Sharp in Areo:

An Oxford undergraduate once wrote a brilliant answer to an exam question about the logic of natural selection, ending with the statement: “And here I rely heavily on the words of Richard Dawkins.” When the exam marker, one Marian Stamp Dawkins, noticed this, she wrote in the margin of the paper: “Yes. Don’t we all?”

An Oxford undergraduate once wrote a brilliant answer to an exam question about the logic of natural selection, ending with the statement: “And here I rely heavily on the words of Richard Dawkins.” When the exam marker, one Marian Stamp Dawkins, noticed this, she wrote in the margin of the paper: “Yes. Don’t we all?”

J. Arvid Ågren relates this anecdote (originally told by Stamp Dawkins herself) in his recent book, The Gene’s-Eye View of Evolution—and he notes how apt it is: Richard Dawkins has had an enormous influence on evolutionary biology since the 1976 publication of his first book, The Selfish Gene (critics and supporters both agree with this—they just differ over whether it is a good thing). The Selfish Gene explains and argues for the gene’s-eye view: the idea that natural selection can best be understood as taking place at the level of the gene, rather than at the level of the individual organism, group or species.

And yet, there has been no recent comprehensive overview until now of the gene’s-eye view that Dawkins did so much to extend and popularise. Thank goodness for Ågren, then: as he notes, evolution is our modern creation story and the gene’s-eye view “strikes right at the heart of the question of what evolution is, and how we go about studying it.”

More here.

The Consequences of Ukraine, 2022

Matthew Nimetz in Quillette:

So much is being written about the Russian invasion of Ukraine that more on the situation on the ground is unnecessary. Certainly, it is premature for a post-mortem on causes and responsibilities of a conflict that came on so quickly and unexpectedly. But it is not a bad time to think about medium- and long-term consequences of Putin’s dramatic action, and how the West can recover its equilibrium and face up to a new global challenge.

So much is being written about the Russian invasion of Ukraine that more on the situation on the ground is unnecessary. Certainly, it is premature for a post-mortem on causes and responsibilities of a conflict that came on so quickly and unexpectedly. But it is not a bad time to think about medium- and long-term consequences of Putin’s dramatic action, and how the West can recover its equilibrium and face up to a new global challenge.

Historians like to argue about whether history is caused primarily by underlying objective forces or by the will of powerful individuals. The Ukrainian case presents that very question. How we in the West answer will influence how we move forward. In this case, some basic forces that have always existed in the central European arena made this confrontation inevitable, as many predicted at the time of the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the expansion of Western influence, and NATO, into the region. But the differences between Moscow and the West over security in central Europe need not have developed into the violent manifestation it has taken, if not for the actions and psyches of key actors.

More here.

Noah Smith interviews Rob Lee, Russian defense policy specialist

What Do Men Want?

Tim Adams in The Guardian:

A few years ago, I sat through an enjoyable lecture by the artist Grayson Perry about the familiar evils of rigid ideas of masculinity: war, imperialism, misogyny, alienation. The lecture was part of a festival called Being a Man (or BAM! for less evolved members of the tribe). Perry ended his comments with a scribbled series of demands on a whiteboard for a new bill of men’s rights, with which it was hard to argue. “We men ask ourselves and each other for the following: the right to be vulnerable, to be uncertain, to be wrong, to be intuitive, the right not to know, to be flexible and not to be ashamed.” He insisted that men sit down and mostly talk quietly to achieve these aims and was given a rousing standing ovation.

A few years ago, I sat through an enjoyable lecture by the artist Grayson Perry about the familiar evils of rigid ideas of masculinity: war, imperialism, misogyny, alienation. The lecture was part of a festival called Being a Man (or BAM! for less evolved members of the tribe). Perry ended his comments with a scribbled series of demands on a whiteboard for a new bill of men’s rights, with which it was hard to argue. “We men ask ourselves and each other for the following: the right to be vulnerable, to be uncertain, to be wrong, to be intuitive, the right not to know, to be flexible and not to be ashamed.” He insisted that men sit down and mostly talk quietly to achieve these aims and was given a rousing standing ovation.

The need for men to be vulnerable, to open up about their insecurities – to become, in cliched terms, more like women – is certainly one antidote to what has become widely understood as the current crisis in masculinity. Thinking about that lecture afterwards, though, it felt a bit limited as a solution. There is no question that mansplainers and manspreaders could do with a fatal dose of humility and doubt. But what about that generation of young men who already feel marginalised from a consumer society, who have been denied most of the markers that traditionally help boys become men: decent jobs, responsible dads, stable homes of their own and, often in consequence, meaningful adult relationships. Would opening up about doubt and vulnerability in itself allow them to achieve self-worth and purpose?

More here.

Bacteria of champions

Karl Kruszelnicki in ABC News:

It’s not just their ability to run 42 kilometres that separates marathon runners from the rest of us. They’ve got a secret energy source hidden deep inside: a special bacteria in their gut turns a painful waste material into energy. No doping scandal required!

It’s not just their ability to run 42 kilometres that separates marathon runners from the rest of us. They’ve got a secret energy source hidden deep inside: a special bacteria in their gut turns a painful waste material into energy. No doping scandal required!

Now if you’ve been following the latest trends in Science for a while, you might remember that about a decade ago, there was a sudden spike of interest in gut bacteria. We had begun to realise just how important the bacteria that live on us, and inside us, actually were. And now, the latest surprising research suggests that these gut bacteria can even help you win a marathon!

But first, a bit of background. You probably know by now that you started off when an egg cell was fertilized by a sperm cell. And by now, there are about 37 trillion cells in your body that all arose from that first fertilized egg cell! Now 37 trillion is a lot of cells — but your body is also home to even more bacterial cells! That’s right – about 40 trillion bacteria live on your skin, inside your gut, and in a few other places. These bacteria are a lot smaller than your human cells, so in total, they weigh only a kilogram or so.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

What to Tell, Still

Reading the galley pages of Laughlin’s Collected Poems

with an eye to writing a comment.

How warmly J speaks of Pound,

……….. I think back to —

At twenty-three I sat in a lookout cabin in gray whipping wind

at the north end of the northern Cascades,

high above rocks and ice, wondering

………. should I go visit Pound at St, Elizabeth’s?

And studied Chinese in Berkley, went to Japan instead.

J puts his love for women

his love for love, his devotion, his pain, his causing-of pain,

………… right out there.

I’m 63 now & I’m on my way to pick up my ten-year-old stepdaughter

……….. and drive the car pool.

I just finished a five-page letter to the County Supervisors

dealing with a former supervisor,

……….. now a paid lobbyist,

who has twisted the facts and gets paid for his lies. Do I

have to deal with this creep? I do.

James Laughlin’s manuscript sitting on my desk.

Late last night reading his clear poems —

and Burt Watson’s volume of translations of Su Shih,

……….. next in line for comment.

September heat.

The Watershed Institute meets,

……….. planning more work with the B.L.M.

And we have visitors from China, Forestry guys,

……….. who want to see how us locals are doing with our plan.

Editorials in the paper are against us,

……….. a botanist is looking at rare plants in the marsh.

I think of how J writes stories of his lovers in his poems —

……….. puts in a lot

……….. it touches me,

So recklessly bold — foolish?

to write so much about your lovers

when you’re a long-married man. Then I think,

what do I know?

……….. About what to say

……….. or not to say, what to tell, or not, to whom,

……….. or when,

……….. still.

by Gary Snyder

from Danger on Peaks

Shoemaker-Hoard, 2004

Charles Mingus Sextet In Stockholm

How A German University Town Helped Usher In The Modern Age

Gary Saul Morson at The American Scholar:

“Perhaps there would be a birth of a whole new era of the sciences and arts,” German romantic thinker Friedrich Schlegel hoped, “if symphilosophy and sympoetry became so universal and heartful that it would no longer be extraordinary for several complementary minds to create communal works of art. One is often struck by the idea that two minds really belong together … to realize their full potential only when joined … an art of amalgamating individuals.”

“Perhaps there would be a birth of a whole new era of the sciences and arts,” German romantic thinker Friedrich Schlegel hoped, “if symphilosophy and sympoetry became so universal and heartful that it would no longer be extraordinary for several complementary minds to create communal works of art. One is often struck by the idea that two minds really belong together … to realize their full potential only when joined … an art of amalgamating individuals.”

By symphilosophy and sympoetry (and other “syms”), Schlegel referred to dialogues in which interlocutors achieve insights otherwise unrealizable. Several minds “amalgamated” this way in the German university town of Jena around 1800.

more here.

The Disruptive Life of Nigel Farage

Steve Richards at Literary Review:

The consequences of Farage’s ubiquity have been seismic, reshaping the UK and the wider political landscape. He sought a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and then a hard Brexit, and ultimately got everything he wanted. The Conservative Party’s embrace of a form of English nationalism was partly a response to the threat that Farage posed. The near-silence of the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, on the subject of Brexit is a form of vindication for him. Starmer knows that Brexit is having calamitous consequences but does not dare to say so. No wonder Michael Crick concludes that ‘it’s hard to think of any other politician in the last 150 years who has had so much impact on British history without being a senior member of one of the major parties at the time’.

The consequences of Farage’s ubiquity have been seismic, reshaping the UK and the wider political landscape. He sought a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and then a hard Brexit, and ultimately got everything he wanted. The Conservative Party’s embrace of a form of English nationalism was partly a response to the threat that Farage posed. The near-silence of the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, on the subject of Brexit is a form of vindication for him. Starmer knows that Brexit is having calamitous consequences but does not dare to say so. No wonder Michael Crick concludes that ‘it’s hard to think of any other politician in the last 150 years who has had so much impact on British history without being a senior member of one of the major parties at the time’.

more here.

Sunday, February 27, 2022

A conversation with Timothy Aubry

Timothy Aubry and Jessica Swoboda in The Point:

Jessica Swoboda: What are the biggest challenges of academic writing?

Jessica Swoboda: What are the biggest challenges of academic writing?

Timothy Aubry: One of the big challenges is that you feel like you have to write in a certain mode. I remember having an inferiority complex in grad school because I felt like no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t make my prose unreadable and complicated and weird and forbidding like all the scholars we were assigned, whether that was Gayatri Spivak, or Judith Butler, or Homi Bhabha, or the academics who were imitating them. They wrote these unbelievably complicated sentences with words like “imbricate,” and “pharmakon,” and “liminal,” and I would try to write papers that sounded like their books and essays, with multiple subclauses that would be hard to decipher. And it was a complete failure.

Over time I did learn to write more in accord with academic protocols and so forth, despite my misgivings. And, according to my family, I do write obscure, unreadable academic prose—so I must have succeeded in getting there to some degree at least.

More here.

Why the Trees Are Marching Northward

Andru Okun in Undark:

Although the speed and severity of climate change are both uncertain, it’s clear by now that warming is inevitable. Rising temperatures will impact every organism on the planet and recast the landscape. In truth, highlights British writer Ben Rawlence, this process is well underway. In “The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth,” he devotes his attention to the boreal forest, also known as the taiga, the broad tract of deciduous and coniferous forests covering the far northern expanses of the Earth. Spanning roughly 1.5 billion acres, the boreal contains a staggering one-third of the Earth’s trees. However, as Rawlence writes, “The trees are on the move.”

Although the speed and severity of climate change are both uncertain, it’s clear by now that warming is inevitable. Rising temperatures will impact every organism on the planet and recast the landscape. In truth, highlights British writer Ben Rawlence, this process is well underway. In “The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth,” he devotes his attention to the boreal forest, also known as the taiga, the broad tract of deciduous and coniferous forests covering the far northern expanses of the Earth. Spanning roughly 1.5 billion acres, the boreal contains a staggering one-third of the Earth’s trees. However, as Rawlence writes, “The trees are on the move.”

As the melting of permafrost and Arctic sea ice hastens atmospheric warming, the boreal is pushing farther north. The implications of this shift are troubling. While southern regions of the boreal have been marred by deforestation, tundra — the typically cold and treeless landscape ringing the North Pole — has begun transforming into woodland. As the trees propagate in formerly barren northern regions, microbial activity is warming the soil further, thawing frozen earth containing large quantities of greenhouse gas.

More here.

Finding the Mother Tree: Uncovering the Wisdom and Intelligence of the Forest

Leon Vlieger in The Inquisitive Biologist:

The idea that trees communicate and exchange nutrients with each other via underground networks of fungi has captured the popular imagination, helped along by the incredibly catchy metaphor of a “wood-wide web”. Suzanne Simard, a Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia, has developed this idea more than anyone else and happily talks of mother trees nurturing their offspring. This idea has not been without controversy in scientific circles, if only for its anthropomorphic language. I was both sceptical and curious about her ideas. High time, therefore, to give her scientific memoir Finding the Mother Tree a close reading.

The idea that trees communicate and exchange nutrients with each other via underground networks of fungi has captured the popular imagination, helped along by the incredibly catchy metaphor of a “wood-wide web”. Suzanne Simard, a Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia, has developed this idea more than anyone else and happily talks of mother trees nurturing their offspring. This idea has not been without controversy in scientific circles, if only for its anthropomorphic language. I was both sceptical and curious about her ideas. High time, therefore, to give her scientific memoir Finding the Mother Tree a close reading.

First, a quick biology lesson to get you up to speed. At the heart of this story are not just trees but foremost fungi. Except for their above-ground fruiting bodies that we call mushrooms, fungi largely weave their way unseen through soil, decaying wood, and other substances. Here, they form mycelium: networks of fine tubular cells.

More here.

Chris Hedges: Chronicle of a War Foretold

Chris Hedges in ScheerPost:

I was in Eastern Europe in 1989, reporting on the revolutions that overthrew the ossified communist dictatorships that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was a time of hope. NATO, with the breakup of the Soviet empire, became obsolete. President Mikhail Gorbachev reached out to Washington and Europe to build a new security pact that would include Russia. Secretary of State James Baker in the Reagan administration, along with the West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, assured the Soviet leader that if Germany was unified NATO would not be extended beyond the new borders. The commitment not to expand NATO, also made by Great Britain and France, appeared to herald a new global order. We saw the peace dividend dangled before us, the promise that the massive expenditures on weapons that characterized the Cold War would be converted into expenditures on social programs and infrastructures that had long been neglected to feed the insatiable appetite of the military.

I was in Eastern Europe in 1989, reporting on the revolutions that overthrew the ossified communist dictatorships that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was a time of hope. NATO, with the breakup of the Soviet empire, became obsolete. President Mikhail Gorbachev reached out to Washington and Europe to build a new security pact that would include Russia. Secretary of State James Baker in the Reagan administration, along with the West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, assured the Soviet leader that if Germany was unified NATO would not be extended beyond the new borders. The commitment not to expand NATO, also made by Great Britain and France, appeared to herald a new global order. We saw the peace dividend dangled before us, the promise that the massive expenditures on weapons that characterized the Cold War would be converted into expenditures on social programs and infrastructures that had long been neglected to feed the insatiable appetite of the military.

There was a near universal understanding among diplomats and political leaders at the time that any attempt to expand NATO was foolish, an unwarranted provocation against Russia that would obliterate the ties and bonds that happily emerged at the end of the Cold War.

More here.

Sunday Poem

“When I Grow Up I Want to Be a Martyr”

is surely a peculiar answer for any teacher to receive when

asking a kindergartner, but on second take, what word best

describes me, crossbreed of butterfly and Super Fly aesthetics,

other than peculiar? I suppose calling me a keen kid would

also suffice in explaining my avidity for the kind of death that

progresses the narrative of a gentling history, because that’s

the only frame for greatness I seem to find for boys my shade

and age to aspire to, short of having the height and hops to

touch the rim, or the bulk and burst to break through the

defensive line like a bullet.

……………………………… And, no, I haven’t given up

on the prospect of Bulls starting shooting guard yet, but

the God-fearer impressed upon me begs the mythology of

goodness delivered to the multitudes like loaves and fish;

……… how King is talked about in black Christian tradition still

……… in mourning over his lost rays of light, the way mentioning

……… the name of Malcolm makes mice of shady white men some

thirty years after the shotgun and he’s sung of as a prince:

I want to evoke that level of pride in American democracy’s

dark downtrodden because I know what it evokes in me,

young and impressionable, watching Denzel’s mimicry

for the one millionth time in my abbreviated existence—

drawing an X on my undeveloped chest, pushing it out

into the unknown-ahead hoping a Mecca for melanin rises

from the man-shaped hole I’d left in my loved one’s lives.

……… I bet my parents would be so proud of me.

I bet post offices would close on my birthday.

I bet God would dap me up

……… when I got up there and Jesus —

……………… dying on a cross to meet me.

by Cortney Lamar Charleston

from Poetry Journal, Vol.211, No. 2 (Nov. 2017

The Poetry Foundayion

Mark Lanegan (1964 – 2022) singer-songwriter