Elizabeth Preston in The New York Times:

The tank looked empty, but turning over a shell revealed a hidden octopus no bigger than a Ping-Pong ball. She didn’t move. Then all at once, she stretched her ruffled arms as her skin changed from pearly beige to a pattern of vivid bronze stripes. “She’s trying to talk with us,” said Bret Grasse, manager of cephalopod operations at the Marine Biological Laboratory, an international research center in Woods Hole, Mass., in the southwestern corner of Cape Cod.

The tank looked empty, but turning over a shell revealed a hidden octopus no bigger than a Ping-Pong ball. She didn’t move. Then all at once, she stretched her ruffled arms as her skin changed from pearly beige to a pattern of vivid bronze stripes. “She’s trying to talk with us,” said Bret Grasse, manager of cephalopod operations at the Marine Biological Laboratory, an international research center in Woods Hole, Mass., in the southwestern corner of Cape Cod.

The tiny, striped octopus is part of an experimental colony at the lab where scientists are trying to turn cephalopods into model organisms: animals that can live and reproduce in research institutions and contribute to scientific study over many generations, like mice or fruit flies do. Cephalopods fascinate scientists for many reasons, including their advanced, camera-like eyes and large brains, which evolved independently from the eyes and brains of humans and our backboned relatives. An octopus, cuttlefish or squid is essentially a snail that swapped its shell for smarts. “They have the biggest brain of any invertebrate by far,” said Joshua Rosenthal, a neurobiologist at the Marine Biological Laboratory. “I mean, it’s not even close.”

More here.

A glance at Hobson-Jobson, the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words in use during the British rule in India, will show that the word “loot” comes into English from Hindi, ultimately deriving from Sanskrit. It entered the English language around the time of the Opium Wars, when the British were not just in India but also in China. This was when the 8th Earl of Elgin, James Bruce, was present at the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing. He was, incidentally, the son of the 7th Lord Elgin who removed the marbles from the Parthenon. James Bruce had this to say about loot:

A glance at Hobson-Jobson, the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words in use during the British rule in India, will show that the word “loot” comes into English from Hindi, ultimately deriving from Sanskrit. It entered the English language around the time of the Opium Wars, when the British were not just in India but also in China. This was when the 8th Earl of Elgin, James Bruce, was present at the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing. He was, incidentally, the son of the 7th Lord Elgin who removed the marbles from the Parthenon. James Bruce had this to say about loot: Languages change continually and in wide variety of ways. New words and phrases appear, while others fall into disuse. Words subtly, or less subtly, shift their meanings or develop new meanings, while speech sounds and intonation change continually. Yet perhaps the most fundamental shift in language change is gradual conventionalization: patterns of communication are initially flexible, but over time they slowly become increasingly stable, conventionalized, and, in many cases, obligatory. This is spontaneous order in action: from an initial jumble increasingly specific patterns emerge over time.

Languages change continually and in wide variety of ways. New words and phrases appear, while others fall into disuse. Words subtly, or less subtly, shift their meanings or develop new meanings, while speech sounds and intonation change continually. Yet perhaps the most fundamental shift in language change is gradual conventionalization: patterns of communication are initially flexible, but over time they slowly become increasingly stable, conventionalized, and, in many cases, obligatory. This is spontaneous order in action: from an initial jumble increasingly specific patterns emerge over time. Antonio Gramsci’s near-feral Sardinian childhood set him apart from most other leading communist revolutionaries of the interwar years, who tended to originate in cities. His father was imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy; his mother scraped by a living mending clothes. When Gramsci was four, a boil on his back began hemorrhaging, and he nearly bled to death. His mother bought a shroud and a small coffin, which stood in a corner of the house for the rest of his youth.

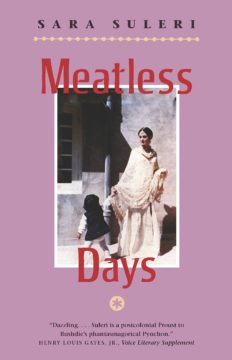

Antonio Gramsci’s near-feral Sardinian childhood set him apart from most other leading communist revolutionaries of the interwar years, who tended to originate in cities. His father was imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy; his mother scraped by a living mending clothes. When Gramsci was four, a boil on his back began hemorrhaging, and he nearly bled to death. His mother bought a shroud and a small coffin, which stood in a corner of the house for the rest of his youth. My friend Professor Tahira Naqvi wrote in her condolence note: “I don’t think there is a book cover that has ever made a place in popular consciousness as that of Meatless Days. I can’t remember a book from my early days here that had as much of an impact as that brilliantly written memoir.”

My friend Professor Tahira Naqvi wrote in her condolence note: “I don’t think there is a book cover that has ever made a place in popular consciousness as that of Meatless Days. I can’t remember a book from my early days here that had as much of an impact as that brilliantly written memoir.” Why do people at the top of their careers snap and make wildly self-destructive moves that rip apart everything they have been working to build? In a blink, Will Smith went from Mr. Nice Guy on the verge of winning an Oscar to a crazed assailant in Satan’s grip. “At your highest moment, be careful. That’s when the devil comes for you,” Smith said in his acceptance speech, quoting what Denzel Washington told him minutes earlier to calm him down.

Why do people at the top of their careers snap and make wildly self-destructive moves that rip apart everything they have been working to build? In a blink, Will Smith went from Mr. Nice Guy on the verge of winning an Oscar to a crazed assailant in Satan’s grip. “At your highest moment, be careful. That’s when the devil comes for you,” Smith said in his acceptance speech, quoting what Denzel Washington told him minutes earlier to calm him down. In the spring of 1947, nothing about the future of India, its identity as a nation or the kind of country it would be, was certain. India would soon be free from British colonial rule, but it could not fulfill the basic needs — let alone the hopes and ambitions — of most of its people. That would require new institutions, new ideas, and men and women who were willing to take a chance on building them.

In the spring of 1947, nothing about the future of India, its identity as a nation or the kind of country it would be, was certain. India would soon be free from British colonial rule, but it could not fulfill the basic needs — let alone the hopes and ambitions — of most of its people. That would require new institutions, new ideas, and men and women who were willing to take a chance on building them. J

J Roth’s most securely canonical work is

Roth’s most securely canonical work is  T

T The vacuum where consequences should be is the setting of Aamina Ahmad’s quietly stunning debut novel, “The Return of Faraz Ali” — stunning not only on account of the writer’s talent, of which there is clearly plenty, but also in its humanity, in how a book this unflinching in its depiction of class and institutional injustice can still feel so tender.

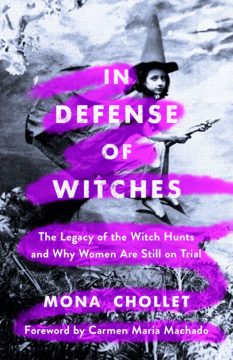

The vacuum where consequences should be is the setting of Aamina Ahmad’s quietly stunning debut novel, “The Return of Faraz Ali” — stunning not only on account of the writer’s talent, of which there is clearly plenty, but also in its humanity, in how a book this unflinching in its depiction of class and institutional injustice can still feel so tender. I’m almost fifty, and over the course of my adult life, the evolution has already been amazing. I grew up in a world where feminists were just a few strange women, always mad, and not to be trusted. Feminism was so unpopular. Now, it’s extraordinary the way young women behave—they don’t want to please men at all costs—and I admire that very much. I was raised to please men and be an “acceptable” woman, to not be angry, or too demanding. I see how young women push that, and push men to evolve and understand things about them. This social blackmail—that if you’re not a “nice” girl, you’ll never be loved—today, they don’t care! My hope is that men will be forced to evolve and be interested in women’s experiences. But it’s a big struggle. In France, I’m really struck by the violent reaction against this. Many men are resisting this evolution with all their strength, because they’ve been living in a world that is so comfortable. It’s really about including your experience of the other in your vision of the world. And many men are not willing to do that.

I’m almost fifty, and over the course of my adult life, the evolution has already been amazing. I grew up in a world where feminists were just a few strange women, always mad, and not to be trusted. Feminism was so unpopular. Now, it’s extraordinary the way young women behave—they don’t want to please men at all costs—and I admire that very much. I was raised to please men and be an “acceptable” woman, to not be angry, or too demanding. I see how young women push that, and push men to evolve and understand things about them. This social blackmail—that if you’re not a “nice” girl, you’ll never be loved—today, they don’t care! My hope is that men will be forced to evolve and be interested in women’s experiences. But it’s a big struggle. In France, I’m really struck by the violent reaction against this. Many men are resisting this evolution with all their strength, because they’ve been living in a world that is so comfortable. It’s really about including your experience of the other in your vision of the world. And many men are not willing to do that.