Maxim D. Shrayer in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

On the night of April 22, the Composer doesn’t sleep …

On the night of April 22, the Composer doesn’t sleep …

Insolent insomnia, he will say to his wife the following morning at breakfast. Kornfleks and kofe with kreem. The neck and jowls of an athlete, the aquiline nose, and the lips of an old camel. A few years ago he could still play a strong game of lawn tennis. Now strictly indoor games. And a jacket with black and white squares. The Composer will let the jacket drop, and then will jot down the word “Petrarch” on an index card of the sort the French call Fiches Bristol.

As soon as Véra has fallen asleep in her bedroom, the Composer starts the preparations.

More here.

Though theorized in the 1930s and

Though theorized in the 1930s and  The term “neoliberalism” is often used to condemn an array of economic policies associated with such ideas as deregulation, trickle-down economics, austerity, free markets, free trade, and free enterprise. As a political movement, neoliberalism is seen as experiencing its breakthrough 40 years ago with the election into office of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. And since the 2007–08 financial crisis, an explosion of academic work and political activism has been devoted to explaining how neoliberalism is fundamentally to blame for the massive growth in inequality.

The term “neoliberalism” is often used to condemn an array of economic policies associated with such ideas as deregulation, trickle-down economics, austerity, free markets, free trade, and free enterprise. As a political movement, neoliberalism is seen as experiencing its breakthrough 40 years ago with the election into office of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. And since the 2007–08 financial crisis, an explosion of academic work and political activism has been devoted to explaining how neoliberalism is fundamentally to blame for the massive growth in inequality. With Russian shells raining down on Ukrainian cities, an uneasy ceasefire in Yemen, the attack on Palestinians at prayer in Jerusalem and many other conflicts around the world, it might seem to some to be inappropriate to talk about peace.

With Russian shells raining down on Ukrainian cities, an uneasy ceasefire in Yemen, the attack on Palestinians at prayer in Jerusalem and many other conflicts around the world, it might seem to some to be inappropriate to talk about peace. Eva Frank was born in 1756, in modern-day Ukraine, to Jacob and Hannah Frank, along with their existing children. Jacob had been raised in a family staunchly committed to the radical teachings of Shabtai Tzvi, the Jewish messianic claimant who died in 1676 after ultimately converting to Islam, and whose widely embraced prophecies and antinomian preaching—which specifically called for overturning Jewish law—nearly upended European Jewry. Around 1751, five years before Eva’s birth, Jacob proclaimed that he was Shabtai Tzvi’s successor on Earth. Building on Jewish mystical teachings and Shabtai Tzvi’s legacy, he fashioned himself as the Messiah on earth who had come to teach a new way of religious life that would bring the Messianic era. He quickly attracted thousands of followers, known as “Frankists”, and reportedly took the antinomian embrace of holy subversion even further than Shabtai Tzvi, hosting intricate rituals that overthrew the taboos of incest, menstruation, and adultery, often with the aid of sacred objects, including Torah scrolls. Though there is ongoing debate about the extent of such rituals in practice, as opposed to simply wild rumors, scholars Cristina Ciucu and Regan Kramer argue in their article published in Clio. Women, Gender, History that

Eva Frank was born in 1756, in modern-day Ukraine, to Jacob and Hannah Frank, along with their existing children. Jacob had been raised in a family staunchly committed to the radical teachings of Shabtai Tzvi, the Jewish messianic claimant who died in 1676 after ultimately converting to Islam, and whose widely embraced prophecies and antinomian preaching—which specifically called for overturning Jewish law—nearly upended European Jewry. Around 1751, five years before Eva’s birth, Jacob proclaimed that he was Shabtai Tzvi’s successor on Earth. Building on Jewish mystical teachings and Shabtai Tzvi’s legacy, he fashioned himself as the Messiah on earth who had come to teach a new way of religious life that would bring the Messianic era. He quickly attracted thousands of followers, known as “Frankists”, and reportedly took the antinomian embrace of holy subversion even further than Shabtai Tzvi, hosting intricate rituals that overthrew the taboos of incest, menstruation, and adultery, often with the aid of sacred objects, including Torah scrolls. Though there is ongoing debate about the extent of such rituals in practice, as opposed to simply wild rumors, scholars Cristina Ciucu and Regan Kramer argue in their article published in Clio. Women, Gender, History that

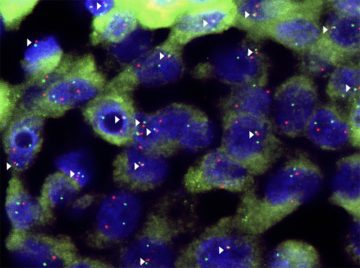

Science is all about expanding the realm of human perception. Sometimes that means making the invisible visible, like when Galileo turned a telescope toward Jupiter, discovered moons around another planet and

Science is all about expanding the realm of human perception. Sometimes that means making the invisible visible, like when Galileo turned a telescope toward Jupiter, discovered moons around another planet and  My gym in the heart of the 19th arrondissement is inhabited by a goodly mix of young Tunisian beefcakes admiring themselves and one another in the full-wall mirrors; older barrel-shaped strongmen, often with moustaches and faded anchor tattoos on their forearms, as if straight off the carnival circuit circa 1910, where you might see them wearing skimpy leopard-spotted togas and lifting those ball-shaped barbells from the cartoons; and a scattering of scrawny ageing bourgeois who are quite plainly there on the stern recommendation of their doctors.

My gym in the heart of the 19th arrondissement is inhabited by a goodly mix of young Tunisian beefcakes admiring themselves and one another in the full-wall mirrors; older barrel-shaped strongmen, often with moustaches and faded anchor tattoos on their forearms, as if straight off the carnival circuit circa 1910, where you might see them wearing skimpy leopard-spotted togas and lifting those ball-shaped barbells from the cartoons; and a scattering of scrawny ageing bourgeois who are quite plainly there on the stern recommendation of their doctors.

The New York Times is obsessed with Substack. A few months ago, it published

The New York Times is obsessed with Substack. A few months ago, it published  FOR THE PAST DECADE,

FOR THE PAST DECADE, When someone’s liver is infected with hepatitis B, damage increases over time, as long as the virus is active. The liver tissue thickens and forms scars (fibrosis), advancing to severe scarring called cirrhosis. In approximately one-third of people with hepatitis B infection, this then progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma, as the viral DNA inserts itself into liver cells, changing their function and allowing tumours to grow.

When someone’s liver is infected with hepatitis B, damage increases over time, as long as the virus is active. The liver tissue thickens and forms scars (fibrosis), advancing to severe scarring called cirrhosis. In approximately one-third of people with hepatitis B infection, this then progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma, as the viral DNA inserts itself into liver cells, changing their function and allowing tumours to grow. Yet this book could not be summarized as a jeremiad against cyberspace, because it, like most of Smith’s essays and scholarship, rarifies its subject through its author’s talent for synthesizing seemingly disparate ideas and endeavors. In building an alternative model of the internet, Smith transports his reader between discussions of Proust and 1940s hunting gadgetry; the signaling of sperm whales and the metaphysics of methyl jasmonate; Melanesian ritual masks and the Kuiper Belt; Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics and Grand Theft Auto; the nascent industry of “teledildonics” and the rueful poetics of railways; Kant’s epistemology and the pablum of Mark Zuckerberg. In a book that meditates upon networks, webs, and connections, Smith’s astounding range becomes something of a method for revealing the interconnectedness of everything between stars and modems.

Yet this book could not be summarized as a jeremiad against cyberspace, because it, like most of Smith’s essays and scholarship, rarifies its subject through its author’s talent for synthesizing seemingly disparate ideas and endeavors. In building an alternative model of the internet, Smith transports his reader between discussions of Proust and 1940s hunting gadgetry; the signaling of sperm whales and the metaphysics of methyl jasmonate; Melanesian ritual masks and the Kuiper Belt; Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics and Grand Theft Auto; the nascent industry of “teledildonics” and the rueful poetics of railways; Kant’s epistemology and the pablum of Mark Zuckerberg. In a book that meditates upon networks, webs, and connections, Smith’s astounding range becomes something of a method for revealing the interconnectedness of everything between stars and modems. There is something irresistible about John Keats’s poignantly brief life and his outsize greatness as an artist. That such a wealth of material about him exists—his own astonishing letters as well as reminiscences and diaries of his friends—means that there has never been a shortage of biographies. Vignettes began appearing soon after Keats’s death in 1821, with the first full biography, by Richard Monckton Milnes (a Victorian politician, failed suitor of Florence Nightingale, and avid collector of erotica), appearing in 1848. More recent lives of the poet include works by Amy Lowell (1924), Robert Gittings (1968), Andrew Motion (1997), and Nicholas Roe (2012), to name a few. Now the English literary journalist and biographer Lucasta Miller has added to the pile. She wrote her book, pegged to the 200th anniversary of Keats’s death, under pandemic lockdown in Hampstead, an area of London where the poet himself lived, a place still haunted by Keatsian associations.

There is something irresistible about John Keats’s poignantly brief life and his outsize greatness as an artist. That such a wealth of material about him exists—his own astonishing letters as well as reminiscences and diaries of his friends—means that there has never been a shortage of biographies. Vignettes began appearing soon after Keats’s death in 1821, with the first full biography, by Richard Monckton Milnes (a Victorian politician, failed suitor of Florence Nightingale, and avid collector of erotica), appearing in 1848. More recent lives of the poet include works by Amy Lowell (1924), Robert Gittings (1968), Andrew Motion (1997), and Nicholas Roe (2012), to name a few. Now the English literary journalist and biographer Lucasta Miller has added to the pile. She wrote her book, pegged to the 200th anniversary of Keats’s death, under pandemic lockdown in Hampstead, an area of London where the poet himself lived, a place still haunted by Keatsian associations.