Rajan Menon in Boston Review:

Rajan Menon in Boston Review:

After a prolonged buildup of forces, the total reaching 120,000 soldiers and National Guard troops, Russian President Vladimir Putin decided on February 24 to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The decision has revived a sharp-elbowed debate in the United States. One side consists mainly, though not exclusively, of those belonging to the realist school of thought. This side insists that Putin’s move can only be understood by taking account of the friction that NATO’s eastward expansion created between Russia and the United States. The other side, primarily comprised of neoconservatives and liberal internationalists, retorts that Putin’s protests against NATO’s enlargement are bogus. They contend that Putin’s animosity toward democracy—particularly the fear that its success in Ukraine would rub off on Russia and bring down the state that he has built since 2000—was the sole reason for the war.

Both sides have succumbed to the single factor fallacy. Given the complexities of history and politics, why should we assume that Putin has only one aim, only one apprehension? In consequence their exchanges have been inconclusive, producing more heat than light. On occasion, there have been simpleminded portrayals of realism in newspaper columns and magazines, and worse, ugly ad hominem attacks. There has been little meaningful debate. Social media has enabled much sound and fury, proving about as productive as a dog’s attempt to chase its tail, albeit much less amusing.

More here.

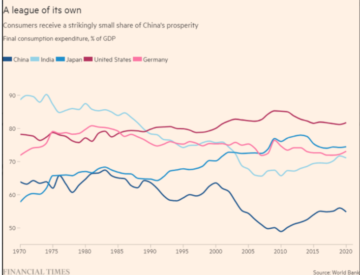

Adam Tooze debates Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu on whether China can make the adjustments necessary to sustain growth.

Adam Tooze debates Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu on whether China can make the adjustments necessary to sustain growth.  James Meadway in Sidecar:

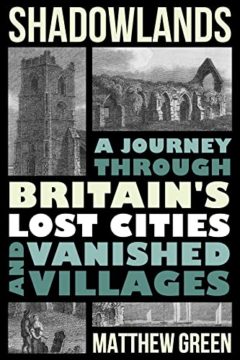

James Meadway in Sidecar: But as Green says, and his book splendidly demonstrates, “what has disappeared beneath sea can rebuild itself in the mind”. Since the 13th century, when the Suffolk coastline by Dunwich began to be seriously gnawed by the waves, thousands of settlements have disappeared from our maps. It is the untold story of these lost communities – “Britain’s shadow topography” – that has become Green’s obsession. He disinters their rich history and reimagines the lives of those who walked their streets, revealing “tales of human perseverance, obsession, resistance and reconciliation”. By doing so, he makes tangible the tragedy of their loss and the threat we all face from the climate crisis on these storm-tossed islands.

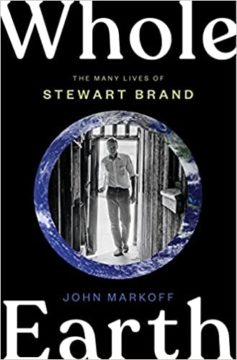

But as Green says, and his book splendidly demonstrates, “what has disappeared beneath sea can rebuild itself in the mind”. Since the 13th century, when the Suffolk coastline by Dunwich began to be seriously gnawed by the waves, thousands of settlements have disappeared from our maps. It is the untold story of these lost communities – “Britain’s shadow topography” – that has become Green’s obsession. He disinters their rich history and reimagines the lives of those who walked their streets, revealing “tales of human perseverance, obsession, resistance and reconciliation”. By doing so, he makes tangible the tragedy of their loss and the threat we all face from the climate crisis on these storm-tossed islands. In 1966, Stewart Brand was an impresario of Bay Area counterculture. As the host of an extravaganza of music and psychedelic simulation called the Trips Festival, he was, according to

In 1966, Stewart Brand was an impresario of Bay Area counterculture. As the host of an extravaganza of music and psychedelic simulation called the Trips Festival, he was, according to  Carl Erik Fisher’s new book, “The Urge: Our History of Addiction,” follows two journeys: One is a memoir of his own addiction to alcohol (he grew up with two alcoholic parents), and the other is a detailed overview of the approaches that have been used to understand, control and treat addiction over time. This last includes the relatively contemporary idea of “recovery,” which suggests that it is possible, with the right medications, such as naloxone, buprenorphine or methadone, and thoughtful care, to break its hold.

Carl Erik Fisher’s new book, “The Urge: Our History of Addiction,” follows two journeys: One is a memoir of his own addiction to alcohol (he grew up with two alcoholic parents), and the other is a detailed overview of the approaches that have been used to understand, control and treat addiction over time. This last includes the relatively contemporary idea of “recovery,” which suggests that it is possible, with the right medications, such as naloxone, buprenorphine or methadone, and thoughtful care, to break its hold. Think about a time when you changed your mind. Maybe you heard about a crime, and rushed to judgment about the guilt or innocence of the accused. Perhaps you wanted your country to go to war, and realise now that maybe that was a bad idea. Or possibly you grew up in a religious or partisan household, and switched allegiances when you got older. Part of maturing is developing intellectual humility. You’ve been wrong before; you could be wrong now.

Think about a time when you changed your mind. Maybe you heard about a crime, and rushed to judgment about the guilt or innocence of the accused. Perhaps you wanted your country to go to war, and realise now that maybe that was a bad idea. Or possibly you grew up in a religious or partisan household, and switched allegiances when you got older. Part of maturing is developing intellectual humility. You’ve been wrong before; you could be wrong now. During a workshop last fall at the Vatican, Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France, gave a presentation chronicling his quest to understand what makes humans — for better or worse — so special.

During a workshop last fall at the Vatican, Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France, gave a presentation chronicling his quest to understand what makes humans — for better or worse — so special.

What often gets left out of chronicles about the Banda Islands, of which there are not many to begin with, are the perspectives of Bandanese survivors of the 1621 genocide, and their efforts to remember the past through stories and song. As Ghosh writes, ‘the modern gaze sees only one of the nutmeg’s two hemispheres… [it] is merely an inert object, a planet that contains no intrinsic meaning, and no properties other than those that make it a subject of science and commerce.’ THE NUTMEG’S CURSE shows us the hemisphere cast in a penumbra. Throughout the book, the chiaroscuro effect is extended to certain words as well, like ‘nature’, whose Western conception, Ghosh observes, ‘is the key element that simultaneously enables and conceals the true character of biopolitical warfare.’ The Bandanese have a very different relationship to nature, they view their islands as ‘places of dwelling that were enmeshed with human life in ways that were imaginative as well as material.’ Ghosh quotes the Indigenous thinker Max Liboiron, for whom land is ‘the unique entity that is the combined living spirit of plants, animals, water, humans, histories, and events.’ This is a ‘vitalist’ way of seeing the world that recognises the agency of material things. It’s also a view that any reader of Ghosh’s work implicitly senses. For those new to his writing, THE NUTMEG’S CURSE is not just a ‘parable for planetary crisis’, but also, albeit to a lesser extent, a kind of onboarding manual for his Ibis triple-decker.

What often gets left out of chronicles about the Banda Islands, of which there are not many to begin with, are the perspectives of Bandanese survivors of the 1621 genocide, and their efforts to remember the past through stories and song. As Ghosh writes, ‘the modern gaze sees only one of the nutmeg’s two hemispheres… [it] is merely an inert object, a planet that contains no intrinsic meaning, and no properties other than those that make it a subject of science and commerce.’ THE NUTMEG’S CURSE shows us the hemisphere cast in a penumbra. Throughout the book, the chiaroscuro effect is extended to certain words as well, like ‘nature’, whose Western conception, Ghosh observes, ‘is the key element that simultaneously enables and conceals the true character of biopolitical warfare.’ The Bandanese have a very different relationship to nature, they view their islands as ‘places of dwelling that were enmeshed with human life in ways that were imaginative as well as material.’ Ghosh quotes the Indigenous thinker Max Liboiron, for whom land is ‘the unique entity that is the combined living spirit of plants, animals, water, humans, histories, and events.’ This is a ‘vitalist’ way of seeing the world that recognises the agency of material things. It’s also a view that any reader of Ghosh’s work implicitly senses. For those new to his writing, THE NUTMEG’S CURSE is not just a ‘parable for planetary crisis’, but also, albeit to a lesser extent, a kind of onboarding manual for his Ibis triple-decker. Let me start by asking, Why a perfume? Why not several? A lot of people have perfume wardrobes. You can have a depersonalized relationship to perfume and just ask, How do I want to smell, in a performative way?

Let me start by asking, Why a perfume? Why not several? A lot of people have perfume wardrobes. You can have a depersonalized relationship to perfume and just ask, How do I want to smell, in a performative way? AS PRIVATE SPACE

AS PRIVATE SPACE  All pandemics end eventually. But how, exactly, will we know when the COVID-19 pandemic is really “over”? It turns out the answer to that question may lie more in sociology than epidemiology.

All pandemics end eventually. But how, exactly, will we know when the COVID-19 pandemic is really “over”? It turns out the answer to that question may lie more in sociology than epidemiology. On July 19, 1923, before

On July 19, 1923, before