Agnieszka Dale at the LARB:

Hodrová was never associated with the dissident movement in the former Czechoslovakia, and none of her writing was published in the underground but half-tolerated samizdat form. As a scholarly woman writing in a rather recondite literary tradition, she probably wasn’t taken very seriously by more “political” (male) authors, and she didn’t really care for them either, it seems. As it turns out, all this has stood her in good stead. The many “banned authors” of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s were finally published in the early 1990s — and then the world basically lost interest in them, paving the way for “new voices” to emerge, including Hodrová’s. After she was awarded the Kafka Prize, whose winners include the likes of Harold Pinter and Margaret Atwood, Hodrová has even been proposed a few times to the Nobel Committee.

Hodrová was never associated with the dissident movement in the former Czechoslovakia, and none of her writing was published in the underground but half-tolerated samizdat form. As a scholarly woman writing in a rather recondite literary tradition, she probably wasn’t taken very seriously by more “political” (male) authors, and she didn’t really care for them either, it seems. As it turns out, all this has stood her in good stead. The many “banned authors” of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s were finally published in the early 1990s — and then the world basically lost interest in them, paving the way for “new voices” to emerge, including Hodrová’s. After she was awarded the Kafka Prize, whose winners include the likes of Harold Pinter and Margaret Atwood, Hodrová has even been proposed a few times to the Nobel Committee.

Although City of Torment is an experimental work, it is not a hard read.

more here.

Kenneth Rosen in Wired News:

THE ACT OF doomscrolling—spinning continuously through bad news despite its disheartening and depressing effects—and social media envy, like the fear of missing out, present greater risks to your health than were previously realized.

THE ACT OF doomscrolling—spinning continuously through bad news despite its disheartening and depressing effects—and social media envy, like the fear of missing out, present greater risks to your health than were previously realized.

A tranche of research over the past few years, amid the global coronavirus pandemic, a rise in armed conflicts, and increased economic woes, has offered a glimpse into what leaves us restless at night and the ways social media and our phones exacerbate feelings of helplessness. Spawning from a sense of inadequacy about one’s appearance or a perceived lack of achievements, anyone scrolling their phones for extended periods and misusing social media faces an elevated risk of depression, anxiety, loneliness, self-harm, and suicide.

But when at least one in five Americans get their news through social media, it seems a near impossibility to disassociate from our digital avatars and the mobile computers we cart with us everywhere. Like most everything in life, moderation is key.

More here.

From Delancey Place:

Legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday’s autobiography is considered an American classic. Co-written with author and journalist William Dufty at a point when much had already been written about her, it is titled Lady Sings the Blues.

Legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday’s autobiography is considered an American classic. Co-written with author and journalist William Dufty at a point when much had already been written about her, it is titled Lady Sings the Blues.

…”The opening line of the book, ‘Mom and Pop were just a couple of kids when they got married,’ was reshaped from the 1945 PM article. In it Billie was asked to talk about her life, and she began by saying that she was born in Baltimore in 1915 of parents who were ‘just a couple of kids.’ When asked what she meant by that, she replied: “‘Mom was 13 … and Pop was 15.’ She paused. ‘Mom’s and Pop’s parents just about had a fit when it happened. They’d never heard of things like that going on in our part of Baltimore. But they were poor kids, Mom and Pop, and when you’re poor you grow up fast.’ “Billie turned her eyes to us, smiled, and her frown disappeared. She lighted a Chesterfield, and began speaking rapidly, between short, reflective pauses. “‘Mom and Pop didn’t get married till I was three years old,’ she said …

“The British magazine the New Statesman later reprinted those sentences and offered prizes for the best ‘similarly explosive first or last sentences from a real or imagined biography.’ Over a hundred readers gave it a try, but the New Statesman awarded only consolation prizes and declared that the contest was more difficult than they had imagined:

“‘Miss Holiday’s explosiveness … is no simple formula. In 23 superbly chosen words, she has established her background, recorded at least five relevant facts, illustrated (by her method of doing so) one facet of her own character and made firm friends with the reader by a breathtaking and slightly naughty denouement. Too many of her imitators felt that vulgarity or sheer improbability were satisfactory substitutes for the artfully conjured impudence and shock which characterized the original.'”

More here.

mid-april, first day

snow finally melted off 270 road

tho all the rocks right where I left’em last year

two turkey hunters already in the parking area

‘that you guys gobbling down Water Canyon?’

‘yeah we saw a flock of ’em way far away

took a Hail Mary shot but nothing’

clean all silverware + dishes

set in sun to dry

sweep + mop upstairs and down around radio repeater

wash windows all four directions

rattles + catwalk clinks + clanks

mustiness of moths and months

winds 10-15 out of the south

cloud cover 15% cirrus to the east over the Sangres

Barb over in Barillas LO not up yet but she did come back

working on her history of the lookouts of Santa Fe

46 degrees turn on oven + crack the door

make gluten free glop for breakfast

add yoghurt granola + nuts (+ honey!)

call Dispatch in-service for the summer

gonna be cold tonight up here at 10,000 feet

still things to unpack from truck:

guitar mandolin computer books clothes zafu

food for a week or more MREs agua

all my old friends: Redondo Valle Caldera el Rio Grande

la Sierra de Nacamiento Cerro Griego Cerro del Pino

San Diego Canyon San Pedro Wilderness

Borrego Mesa Paliza Canyon

Sandia + Mt Taylor across the flatlands

the pondos + PJ + goddamn rock squirrels

waiting to burrow up in my air filter

nothing but time

brew first cup of tea

sit down + look out

Pico Iyer in Guernica:

Travel is, deep down, an exercise in trust, and sometimes I think it was you who became my life’s most enduring teacher. I had every reason to be wary when, in 1985, I clambered out of the overnight train and stepped out into the October sunshine of Mandalay, blinking amidst the dust and bustle of the “City of Kings.” I wasn’t reassured as you sprang out of the rickety bicycle trishaw in which you’d been sleeping, as you did every night, and I don’t think the signs along the sides of your vehicle — b.sc. (maths) and my life — put my mind very much to rest.

Travel is, deep down, an exercise in trust, and sometimes I think it was you who became my life’s most enduring teacher. I had every reason to be wary when, in 1985, I clambered out of the overnight train and stepped out into the October sunshine of Mandalay, blinking amidst the dust and bustle of the “City of Kings.” I wasn’t reassured as you sprang out of the rickety bicycle trishaw in which you’d been sleeping, as you did every night, and I don’t think the signs along the sides of your vehicle — b.sc. (maths) and my life — put my mind very much to rest.

To me it seemed like a bold leap of faith — a shot in the dark — to allow a rough-bearded man in a cap to pedal me away from the broad main boulevards and into the broken backstreets, and then to lead me into the little hut where you shared a tiny room with a tired compatriot. Yes, you gave me a piece of jade as we rode and disarmed me with the essays you’d written and now handed me on how to enjoy your town. But I’d grown up on stories of what happens when you’re in a foreign place and recklessly neglect a mother’s advice to never accept gifts from strangers.

More here.

Philip Ball in Scientific American:

In case you had not noticed, computers are hot—literally. A laptop can pump out thigh-baking heat, while data centers consume an estimated 200 terawatt-hours each year—comparable to the energy consumption of some medium-sized countries. The carbon footprint of information and communication technologies as a whole is close to that of fuel use in the aviation industry. And as computer circuitry gets ever smaller and more densely packed, it becomes more prone to melting from the energy it dissipates as heat.

In case you had not noticed, computers are hot—literally. A laptop can pump out thigh-baking heat, while data centers consume an estimated 200 terawatt-hours each year—comparable to the energy consumption of some medium-sized countries. The carbon footprint of information and communication technologies as a whole is close to that of fuel use in the aviation industry. And as computer circuitry gets ever smaller and more densely packed, it becomes more prone to melting from the energy it dissipates as heat.

Now physicist James Crutchfield of the University of California, Davis, and his graduate student Kyle Ray have proposed a new way to carry out computation that would dissipate only a small fraction of the heat produced by conventional circuits.

More here.

Michael Galway at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation:

Thousands of health workers around the world hunt for polio in two ways: By looking for signs of acute flaccid paralysis in children and testing the environment for the presence of the virus. In Pakistan, for the first time ever, both sets of data look promising: There hasn’t been a single child paralyzed by wild poliovirus in more than a year or any virus detected in the environment in more than two months.

Thousands of health workers around the world hunt for polio in two ways: By looking for signs of acute flaccid paralysis in children and testing the environment for the presence of the virus. In Pakistan, for the first time ever, both sets of data look promising: There hasn’t been a single child paralyzed by wild poliovirus in more than a year or any virus detected in the environment in more than two months.

This morning, I accompanied Bill Gates to Pakistan’s National Emergency Operations Center in Islamabad because he wanted to see the progress for himself. We got to listen in as the team leading Pakistan’s program pored over a huge trove of data and debated what it was telling them about how to reach more children in the next house-to-house vaccination campaign, which starts a week from now.

More here.

David Sloan Wilson and Dennis J. Snower in Evonomics:

DSW: Greetings, Dennis! I look forward to discussing the backstory of our article. Let’s begin with how we met, which says a lot about the need for paradigmatic change. It was a workshop organized by a major foundation to explore how to go beyond neoclassical economics. The participants were drawn from a number of academic disciplines such as law, political science, and sociology in addition to economics. Each discipline had its own table, so the layout of the room reflected the siloed nature of the disciplines. I was the only person with evolutionary training, so I was assigned to the sociology table. That’s ironic, because sociology is even further behind economics in embracing evolutionary science.

DSW: Greetings, Dennis! I look forward to discussing the backstory of our article. Let’s begin with how we met, which says a lot about the need for paradigmatic change. It was a workshop organized by a major foundation to explore how to go beyond neoclassical economics. The participants were drawn from a number of academic disciplines such as law, political science, and sociology in addition to economics. Each discipline had its own table, so the layout of the room reflected the siloed nature of the disciplines. I was the only person with evolutionary training, so I was assigned to the sociology table. That’s ironic, because sociology is even further behind economics in embracing evolutionary science.

I learned a lot from the workshop, including how much the neoclassical paradigm has influenced law in addition to economics. But by the end I became depressed, as table after table reported that this kind of transdisciplinary endeavor would not be career-enhancing within their respective disciplines. It was clear that the siloed nature of the human-related academic disciplines was not going to break down anytime soon, no matter how much money was thrown at it.

More here.

Elżbieta Drążkiewicz in Nature:

In 2019, a senior colleague warned me that my research focus was a niche area of a frivolous topic: conspiracy theories related to vaccine hesitancy among parents in Ireland.

In 2019, a senior colleague warned me that my research focus was a niche area of a frivolous topic: conspiracy theories related to vaccine hesitancy among parents in Ireland.

My area is niche no longer. Motivated to end the pandemic, and to encourage vaccination and other health-promoting behaviours, many researchers new to the subject are asking how best to ‘confront’ or ‘fight’ conspiracy theories, and how to characterize people wary of medical technologies. But my field has worked for decades to push back on this tendency to pathologize and ‘other’. Whether researchers are trying to understand beliefs around vaccination or theories surrounding NATO, Russia and bioweapons labs, such framing limits what can be learnt.

Conspiracy theories are more about values than about information. Debunking statements might occasionally be effective, but does little to tackle their root cause. When investigators ask only about knowledge, they tend to see only ignorance as the root of the problem.

More here.

E.J. Dionne Jr. and Miles Rapoport at Literary Hub:

One hundred percent democracy sounds like a grade someone has achieved in a course—and we would like to believe that our American system can be remade to live up to its promise and become worthy of such acclaim.

One hundred percent democracy sounds like a grade someone has achieved in a course—and we would like to believe that our American system can be remade to live up to its promise and become worthy of such acclaim.

It refers specifically to the aspiration that every American be guaranteed the right to vote—with ease and without obstruction—and that our nation recognize that every citizen, as a matter of civic duty, has an obligation to participate in the shared project of democratic self-government. We want to make the case for what Australians refer to as “compulsory attendance at the polls” and what we call universal civic duty voting.

We see voting as a public responsibility of all citizens, no less important than jury duty. If every American citizen is required to vote as a matter of obligation, the representativeness of our elections would increase. Those responsible for organizing elections would be required to resist all efforts at voter suppression and remove barriers to the ballot box. We believe that universal civic duty voting is the decisive step toward putting an end, once and for all, to legal assaults on voting rights.

More here.

From Phys.Org:

Parrots are famous for their remarkable cognitive abilities and exceptionally long lifespans. Now, a study led by Max Planck researchers has shown that one of these traits has likely been caused by the other. By examining 217 parrot species, the researchers revealed that species such as the scarlet macaw and sulfur-crested cockatoo have extremely long average lifespans, of up to 30 years, which are usually seen only in large birds. Further, they demonstrated a possible cause for these long lifespans: large relative brain size. The study is the first to show a link between brain size and lifespan in parrots, suggesting that increased cognitive ability may have helped parrots to navigate threats in their environment and to enjoy longer lives.

Parrots are famous for their remarkable cognitive abilities and exceptionally long lifespans. Now, a study led by Max Planck researchers has shown that one of these traits has likely been caused by the other. By examining 217 parrot species, the researchers revealed that species such as the scarlet macaw and sulfur-crested cockatoo have extremely long average lifespans, of up to 30 years, which are usually seen only in large birds. Further, they demonstrated a possible cause for these long lifespans: large relative brain size. The study is the first to show a link between brain size and lifespan in parrots, suggesting that increased cognitive ability may have helped parrots to navigate threats in their environment and to enjoy longer lives.

…”Living an average of 30 years is extremely rare in birds of this size,” says Smeele who worked closely with Lucy Aplin from MPI-AB and Mary Brooke McElreath from MPI-EvA on the study. “Some individuals have a maximum lifespan of over 80 years, which is a respectable age even for humans. These values are really spectacular if you consider that a human male weights about 100 times more.

More here.

Rachel Miller in Vox:

Forgiveness is often viewed as the “happily ever after” ending in a story of wrongdoing or injustice. Someone enacts harm, the typical arc goes, but eventually sees the error of their ways and offers a heartfelt apology. “Can you ever forgive me?” Then you, the hurt person, are faced with a choice: Show them mercy — granting yourself peace in the process — or hold a grudge forever. The choice is yours, and it’s one many of us assume starts with remorse and a plea for grace.

Forgiveness is often viewed as the “happily ever after” ending in a story of wrongdoing or injustice. Someone enacts harm, the typical arc goes, but eventually sees the error of their ways and offers a heartfelt apology. “Can you ever forgive me?” Then you, the hurt person, are faced with a choice: Show them mercy — granting yourself peace in the process — or hold a grudge forever. The choice is yours, and it’s one many of us assume starts with remorse and a plea for grace.

It’s reasonable to expect an apology when you’re the one who has been hurt or betrayed. But that’s not how it works in practice. In fact, therapist Harriet Lerner writes in her book Why Won’t You Apologize?: Healing Big Betrayals and Everyday Hurts, the worse the offense, the more difficult it can be to get an apology from the person who harmed you. In those instances, Lerner writes, “Their shame leads to denial and self-deception that overrides their ability to orient toward reality.” And beyond this, there are other reasons you might be unable to get the apology you deserve. Maybe the other person isn’t aware of the harm they did to you, or they’ve disappeared, making contact impossible, or they’ve died.

Unfortunately, that puts you in a tough spot. How do you forgive someone who isn’t all that sorry, or who you can’t actually engage with?

More here.

Benjamin Ivry at Salmagundi:

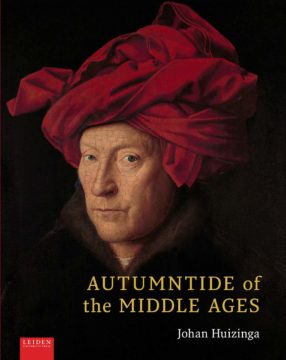

Although Autumntide may seem ornately literary today, when it was first published, some historians criticized its racy readability. Otto Oppermann, a German-Dutch medievalist who taught at Utrecht, referred to the book as “Huizinga’s crime novel,” implying that it was all too vivid an experience.

Although Autumntide may seem ornately literary today, when it was first published, some historians criticized its racy readability. Otto Oppermann, a German-Dutch medievalist who taught at Utrecht, referred to the book as “Huizinga’s crime novel,” implying that it was all too vivid an experience.

What appeared inappropriate to some academics a century ago has bolstered the book’s enduring charm. The historian William J. Bouwsma pointed out in the winter 1974 issue of Daedalus that Autumntide may be “enjoyed as a work of high art, full of color and life, as in its marvelous opening chapter with its bells and processions, its public executions and public tears…[Huizinga] had a singularly original and stimulating mind, provocative even when it seems most limited and perverse.”

more here.

Thomas de Monchaux at n+1:

This sort of loss, with its confluence of profligacy and jackassery, is a common feature of architectural history. Any speculator who demolishes Geller I to build a tennis court is assuredly some sort of villain, but the villainy is also of a system within which such actions can seem rational and normal. Even after the housing bubble and Great Recession, sometimes fantastical speculation in the material value of private houses and their half-acres of land remains the seeming consolation for the compounding economic injustices of our new Gilded Age—especially for the middle classes, for whom their dwelling place is their main financial asset. I’m reminded of Walt Whitman’s father—also a Long Island house-flipper and land speculator—remembered in There was a Child Went Forth as a master of “the blow . . . the tight bargain, the crafty lure.” The transactionality of those encounters colonized the consciousness of the poet inseparably from “the streets themselves, and the façades of the houses. . . . the goods in the windows.”

This sort of loss, with its confluence of profligacy and jackassery, is a common feature of architectural history. Any speculator who demolishes Geller I to build a tennis court is assuredly some sort of villain, but the villainy is also of a system within which such actions can seem rational and normal. Even after the housing bubble and Great Recession, sometimes fantastical speculation in the material value of private houses and their half-acres of land remains the seeming consolation for the compounding economic injustices of our new Gilded Age—especially for the middle classes, for whom their dwelling place is their main financial asset. I’m reminded of Walt Whitman’s father—also a Long Island house-flipper and land speculator—remembered in There was a Child Went Forth as a master of “the blow . . . the tight bargain, the crafty lure.” The transactionality of those encounters colonized the consciousness of the poet inseparably from “the streets themselves, and the façades of the houses. . . . the goods in the windows.”

more here.

I swim with others.

Some are dolphins, some are sharks.

Which is which depends on the temperature of the water

or the weather. Something: it’s not clear.

From whale song to hammerhead thrash,

they change their tune at the drop of a mask

over the side, pulled deep by invisible cable

to pressurised obscurity.

Before I know it the warm, blue shallows shelve

into coldness. Gloom wraps me in panic.

I pray. My prayer says:

“Even turtles nip if they think you’re edible.”

Overwhelming, but it’s either that

or swim alone.

by Robin Knight

from Rattle #71, Spring 2021; Tribute

to Neurodiversity

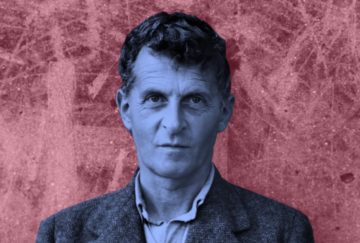

Kieran Setiya in the Boston Review:

The month is May 1916. In southern Galicia, now Ukraine, on the Eastern Front of World War I, a twenty-seven-year-old Austrian volunteers for duty in an observation post exposed to enemy gunfire. He keeps a notebook of his hopes and fears, written in a simple cipher from his childhood—the letter “z” stands for “a,” “y” for “b,” and so on—with philosophical remarks, uncoded, on the facing pages. The latter concern the nature of logic and are peppered with logical symbols. From April 15: “Every simple proposition can be brought into the form ɸx.”

The month is May 1916. In southern Galicia, now Ukraine, on the Eastern Front of World War I, a twenty-seven-year-old Austrian volunteers for duty in an observation post exposed to enemy gunfire. He keeps a notebook of his hopes and fears, written in a simple cipher from his childhood—the letter “z” stands for “a,” “y” for “b,” and so on—with philosophical remarks, uncoded, on the facing pages. The latter concern the nature of logic and are peppered with logical symbols. From April 15: “Every simple proposition can be brought into the form ɸx.”

In June Russia launches the “Brusilov Offensive,” one of the most lethal military campaigns of the war. The young man’s notebook goes empty for a month. Then, on July 4, he begins to write, in the uncoded pages, remarks that are not logical, but spiritual. “What do I know about God and the purpose of life?” he asks. “That something about it is problematic, which we call its meaning. That this meaning does not lie in it but outside it. . . . I cannot bend the happenings of the world to my will; I am completely powerless.”

From this point on, distinctions blur. The cipher seeks connections; the philosophy leaps from logic to life’s meaning and back. “Yes,” he writes on August 2, “my work has broadened out from the foundations of logic to the nature of the world.” In the end, there is no code. Nothing is hidden—though “What cannot be said, cannot be said!”

More here.