Jeff Sharlet in Bookforum:

Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability.

Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability.

I STARTED WRITING THIS ESSAY on the hate under which we all now live the night of Trump’s first debate with Joe Biden. I was trying to think through two new books, Seyward Darby’s Sisters in Hate and Jean Guerrero’s Hatemonger, both smartly reported and urgent. But I stalled. I could read the books, but I didn’t know if I had it in me to write about them. I’d learned, like so many of us, to look away.

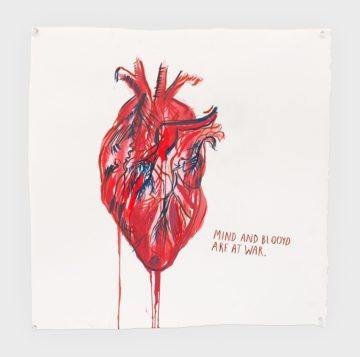

I hadn’t given up the hate beat entirely since my heart attack. I’d grown careful.

Last fall, when I started reporting on Trump rallies again, instead of drinking my fear into submission afterward, I’d go for long walks. I read these books while walking the dirt roads where I live now, roads so quiet I could walk and read. But often I’d pause, neither reading nor walking. I considered the question of how to write about hate, what these books—Darby’s, on the internal lives of female leaders of what remains (for now) fringe white nationalism, and Guerrero’s, about Trump senior adviser and speechwriter Stephen Miller, who is mainstreaming those beliefs—might say about the taxonomy of hate, the methodology of its study. As if looking at hate was a matter of professional curiosity.

I had thoughts! But I couldn’t keep what I’d read in my mind, my gut, my—maybe you’ll forgive the cliché—my heart. I’d reached saturation. Or maybe I was finally getting it, the “joke,” which is that you don’t need to go looking for hate. It’s always right there, mundane. I remembered a 2017 New York Times profile of a suburban neo-Nazi, how many accused it of “normalizing” its subject. I hadn’t thought much of it—no need to play neutral with fascism—but I hadn’t agreed when people said it didn’t matter if the Nazi liked Seinfeld and Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim. I thought there was no “normalizing” him, because he was all too normal. It seemed critical to understand the ways in which the antifascist del Toro’s art could be repurposed as hate. If it could happen to del Toro it could happen to anybody. We are, none of us, especially given the whiteness—the anti-Blackness—coded within us all by white supremacy, as far from the Nazi as we want to be. My problem with the Nazi next door wasn’t that we knew too much about him. We didn’t know enough.

More here.