Category: Recommended Reading

A CRISPR view of gene function

From Nature:

Benjamin Izar is trying to work out what happens when immune cells encounter cancer cells. He starts with large molecular profiling studies, such as whole-exome sequencing and RNA-seq. “They give dozens of putative targets or mechanisms that may play a role in disease or drug response, but it is impossible to functionally validate each of them individually,” he laments.

To help, Izar, a physician-scientist at Columbia University’s Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center in New York, turned to CRISPR screens. CRISPR allows researchers to precisely alter cells’ DNA sequences, and modify gene function. With high-throughput screens, the effects of thousands of perturbations can be assessed in a single experiment. These tools aid research and drug discovery efforts by helping scientists identify the genetic variations, in both coding and non-coding regions, that contribute to disease.

However, until now, typical read-outs of CRISPR screens under different conditions, such as drug treatment or viral infection, have been quite simple cell growth and survival assays. These read-outs reveal genes that, when disturbed, either sensitize or confer a selective advantage to the challenged cells — but with no indication of how they do so. Newly developed techniques provide single-cell, multi-omic readouts of CRISPR-modified cells. “Any large-scale profiling or screening effort may benefit from such methods as they help drill down to what might be functionally relevant,” says Izar. With these ‘high-content’ CRISPR screens, researchers can start to evaluate the myriad nominated mechanisms and targets.

More here.

Rectal Cancer Disappears After Experimental Use of Immunotherapy

From MSKCC:

Sascha Roth remembers the phone call came on a hectic Friday evening. She was racing around her home in Washington, D.C., to pack for New York, where she was scheduled to undergo weeks of radiation therapy for rectal cancer. But the phone call from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) medical oncologist Andrea Cercek changed everything, leaving Sascha “stunned and ecstatic — I was so happy.” Dr. Cercek told Sascha, then 38, that her latest tests showed no evidence of cancer, after Sascha had undergone six months of treatment as the first patient in a clinical trial involving immunotherapy at MSK.

Sascha Roth remembers the phone call came on a hectic Friday evening. She was racing around her home in Washington, D.C., to pack for New York, where she was scheduled to undergo weeks of radiation therapy for rectal cancer. But the phone call from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) medical oncologist Andrea Cercek changed everything, leaving Sascha “stunned and ecstatic — I was so happy.” Dr. Cercek told Sascha, then 38, that her latest tests showed no evidence of cancer, after Sascha had undergone six months of treatment as the first patient in a clinical trial involving immunotherapy at MSK.

Immunotherapy harnesses the body’s own immune system as an ally against cancer. The MSK clinical trial was investigating — for the first time ever — if immunotherapy alone could beat rectal cancer that had not spread to other tissues, in a subset of patients whose tumor contain a specific genetic mutation. “Dr. Cercek told me a team of doctors examined my tests,” recalls Sascha. “And since they couldn’t find any signs of cancer, Dr. Cercek said there was no reason to make me endure radiation therapy.”

These same remarkable results would be repeated for all 14 people — and counting — in the MSK clinical trial for rectal cancer with a particular mutation. While it’s a small trial so far, the results are so impressive they were published in The New England Journal of Medicine and featured at the nation’s largest gathering of clinical oncologists in June 2022. In every case, the rectal cancer disappeared after immunotherapy — without the need for the standard treatments of radiation, surgery, or chemotherapy — and the cancer has not returned in any of the patients, who have been cancer-free for up to two years. “It’s incredibly rewarding,” says Dr. Cercek, “to get these happy tears and happy emails from the patients in this study who finish treatment and realize, ‘Oh my God, I get to keep all my normal body functions that I feared I might lose to radiation or surgery.’ ”

More here.

IDLES Full Set | From The Basement

Wednesday Poem

Le Vent Sauvage

The Clouds they come to greet me.

I kiss their furrowed brows.

Though they cannot hold me,

I respect their somber songs.

I live in the moon shade,

and travel by day’s breath.

I dance on the grass reeds,

and play with rivers wild.

For I am owned by no one,

and am the sky’s own child.

by Celine Beaulieu

from The Rutherford Red Wheelbarrow

Red Wheelbarrow Poets, 2010

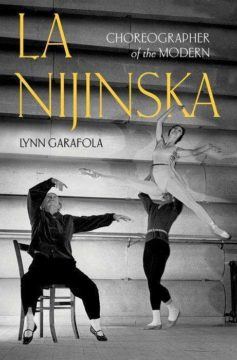

La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern

Marcia B. Siegel at The Hudson Review:

Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern.

Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern.

more here.

Franz Kafka: The Drawings

George Prochnik at Literary Review:

Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest.

Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest.

In two of the early single-page sketches, the human subjects – one on foot, the other riding a horse – are reduced so entirely to curling and back-slanting flourishes that they resemble lines drawn to indicate wind or the displacement of air surrounding figures in motion rather than figures themselves. Even when Kafka’s subjects are depicted on chairs or penned within enclosures in positions ordinarily associated with stationary conditions, their poses are so dynamically strained as to inject the immobilised state with high kinetic tension. Here, movement and the repressed urge thereto appear as traces of a primal survival instinct. ‘Mount your attacker’s horse and ride it yourself,’ Kafka wrote in one frantic diary entry. ‘The only possibility. But what strength and skill that requires! And how late it is already!’

more here.

Tuesday, June 7, 2022

Notes on the Vibe Shift

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack newsletter, The Hinternet:

Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on.

Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on.

The gentle shift one has to make to reconcile all these false friends occurs not only at the lexical level, but also in morphology and phonology, and once it takes place one starts to discern the likenesses of outre-Manche cousins that previously remained hidden: thus Guillaume is the cousin of William, and gardien of warden, and guichet of wicket, and guerre of war.

More here.

Noam Chomsky and GPT-3

Gary Marcus in his Substack newsletter:

Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a natural metaphor for the mind.

Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a natural metaphor for the mind.

The latest hypothesis to attract notice, both within the scientific community, and in the world at large, is the notion that a technology that is popular today, known as large language models, such as OpenAI’s GPT-3, might offer important insight into the mechanics of the human mind. Enthusiasm for such models has grown rapidly; OpenAI’s Chief Science Officer Ilya Sutskever recently suggested that such systems could conceivably be “slightly conscious”. Others have begun to compare GPT with the human mind.

That GPT-3, an instance of a kind of technology known as a “neural network”, and powered by a technique known as deep learning, appears clever is beyond question – but aside from their possible merits as engineering tools, one can ask another question: are large language models a good model of human language?

More here.

When Jawaharlal Nehru read ‘Lolita’ to decide whether an ‘obscene’ book should be allowed in India

Shubhneet Kaushik at Scroll.in:

In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book.

In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book.

The book in question was Lolita, written by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, and published in 1955.

A month earlier, on April 6, 1959, the collector of Customs in Bombay had detained a consignment that included imported copies of the novel belonging to Jaico Publishing House. The collector of Customs referred the matter to the police, the Ministry of Law as well as the Ministry of Finance.

More here.

The Biggest Project in Modern Mathematics

[More at Quanta here.]

Writing Is a Monstrous Act: A Conversation with Hernan Diaz

Rhian Sasseen talks to Hernan Diaz at The Paris Review:

There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature?

There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature?

more here.

Arcades, Churches and Laundromats: A Trucker’s Haven

Jamie Lee Taete at the New York Times:

In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home.

In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home.

Small truck stops have just a few parking spots. By contrast, the Iowa 80 Truck stop, in Walcott, Iowa, bills itself as the largest truck stop in the world and has 900. Across the country, entire temporary cities form and disperse daily.

“Everybody has different stories,” Elaine Peralta said of the truckers that pass through her salon inside the TA Travel Center in Barstow, Calif. “There’s a lot of couples that are driving. There’s a lot of students driving. Young people are driving, and they do their school work, if they’re in college, on the truck. A lot of different ages.”

more here.

Two January 6th Defendants and the Consolidation of Right-Wing Extremism

Bernstein and Marritz in The New Yorker:

In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. After three hours of deliberations, a federal jury found Reffitt guilty on all five counts, including entering a restricted area with a firearm and obstructing an official proceeding. After the verdict, Reffitt returned to the section of the District of Columbia jail where, for more than a year, the mostly white rioters have been held separately from the jail’s mostly Black and brown general population. The January 6th defendants call it the “patriot wing.” Each night, they sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” together.

In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. After three hours of deliberations, a federal jury found Reffitt guilty on all five counts, including entering a restricted area with a firearm and obstructing an official proceeding. After the verdict, Reffitt returned to the section of the District of Columbia jail where, for more than a year, the mostly white rioters have been held separately from the jail’s mostly Black and brown general population. The January 6th defendants call it the “patriot wing.” Each night, they sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” together.

Reffitt resumed his jailhouse pastime, playing Magic: The Gathering—a card game that involves wizards, spells, and strategy—with Jessica Watkins, a bartender and militia leader from rural Ohio who is awaiting trial on seditious conspiracy, obstruction of an official proceeding, and four other charges. Watkins has pleaded not guilty. Of the more than eight hundred people charged with participating in the insurrection at the Capitol, Reffitt and Watkins have been accused of some of the most significant crimes.

Since meeting in jail, they have become close friends. With other defendants, they helped start the tradition of singing the national anthem, Watkins said. She taught Reffitt how to play Magic using copies of cards that her fiancé had sent her. In a message sent on a jail-approved e-mail system, Watkins called the game “cardboard crack,” because it’s so addictive. “I tear the pictures in half neatly to make two magic cards, and I’ve taught my fellow inmates to play,” she wrote. Reffitt, in a message of his own, said that he loves Magic as well. “It’s a very intellectual game and keeping focus can be strained in this environment,” Reffitt wrote. “We tune out the loud noises when we can, the noise level is very stressing.”

More here.

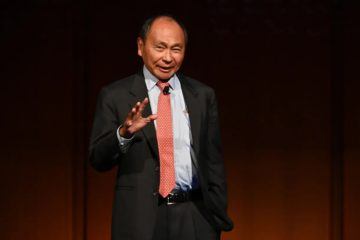

The end of history is history

Sean Illing in Vox:

Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades.

Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades.

He’s best known for his 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man, which arrived on the scene as the Cold War was ending. Fukuyama’s central claim was that liberal democracy had won the war of ideas and established itself as the ideal political system. Not every society around the world was a liberal democracy. But what Fukuyama meant by declaring it “the end of history” was that it was only a matter of time. The claim made a big splash.

Now, 30 years later, Fukuyama’s written a new book called Liberalism and its Discontents. It’s both a defense of liberalism and a critique of it. It does a great job of cataloging the problems of liberalism, but also argues that liberalism is still the best option there is. Fukuyama writes about some very current challenges, like the American right’s move toward authoritarianism, and the resurgence of nationalism around the world. The upshot: It’s not clear that liberal democracy really is the end of history. I reached out to Fukuyama for a recent episode of Vox Conversations. We discuss the promise of liberalism, whether he thinks it’s failing, and if there’s anything he’d like to revise about his end of history thesis.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Dawn

It was not the beginning

Nor the end

Taking this for that

We stumbled

And lost our way

Less free now

to go to our temples

Doors battered, broken, boarded

We stumbled

And lost our way

Regroup

Retreat

Advance anew

There is a dawn

Not this dawn

Nor that dawn

But a dawn

We’ll know

When the light falls

On all of us

All of us

ALL of us.

____________

subh-e aazaadii. Translations in Baran Farooqi, Khalid Hasan,

Shiv Kumar, Victor Kierman.

by Anjum Altaf

from More Transgressions,

Poems inspired by Faiz Ahmed Faiz

LG Publishers Distributors, Delhi, 2021

‘On Love: Selected Writings’, by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

Paul O’Mahoney at the Dublin Review of Books:

Nietzsche’s protest that one cannot cleave to a moral system originating in Christianity after denying the Christian God has implications far more profound than appear at first blush. Nietzsche could already see that purportedly secular doctrines in the ascendancy in his time, and which looked set to become orthodoxy – the sanctity and inherent dignity of human life, the fundamental equality of human lives – were in their origin and character inescapably Christian. It was an absurdity, he felt, that people should, at the moment of the “death of God”, cleave all the more fiercely to the doctrines which depended on Him; or to imagine that one could keep and could promote the gamut of Christian virtues – lovingkindness, humility, charity, counsels of gentleness or forgiveness – when the religious-metaphysical belief system underpinning them had been renounced. If one gives up the God, one ought also, or must also, for the sake of what Nietzsche called one’s intellectual conscience, give up the teachings of the religion. In this Nietzsche foresaw the coming orthodoxy of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: secularised Christianity that calls itself by the names of humanism, egalitarianism, human rights, and which (quite unknowingly) preaches Christianity without Christ.

Nietzsche’s protest that one cannot cleave to a moral system originating in Christianity after denying the Christian God has implications far more profound than appear at first blush. Nietzsche could already see that purportedly secular doctrines in the ascendancy in his time, and which looked set to become orthodoxy – the sanctity and inherent dignity of human life, the fundamental equality of human lives – were in their origin and character inescapably Christian. It was an absurdity, he felt, that people should, at the moment of the “death of God”, cleave all the more fiercely to the doctrines which depended on Him; or to imagine that one could keep and could promote the gamut of Christian virtues – lovingkindness, humility, charity, counsels of gentleness or forgiveness – when the religious-metaphysical belief system underpinning them had been renounced. If one gives up the God, one ought also, or must also, for the sake of what Nietzsche called one’s intellectual conscience, give up the teachings of the religion. In this Nietzsche foresaw the coming orthodoxy of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: secularised Christianity that calls itself by the names of humanism, egalitarianism, human rights, and which (quite unknowingly) preaches Christianity without Christ.

more here.

Sunday, June 5, 2022

Sunday Poem

A Modified Villanelle for My Childhood

I wanna write lyrical, but all I got is magical.

My book needs a poem talkin bout I remember when

Something more autobiographical

Mi familia wanted to assimilate, nothing radical,

Each month was a struggle to pay our rent

With food stamps, so dust collects on the magical.

Each month it got a little less civil

Isolation is a learned defense

When all you wanna do is write lyrical.

None of us escaped being a criminal

Of the state, institutionalized when

They found out all we had was magical.

White room is white room, it’s all statistical—

Our calendars were divided by Sundays spent

In visiting hours. Cold metal chairs deny the lyrical.

I keep my genes in the sharp light of the celestial.

My history writes itself in sheets across my veins.

My parents believed in prayer, I believed in magical

Well, at least I believed in curses, biblical

Or not, I believed in sharp fists,

Beat myself into lyrical.

But we were each born into this, anger so cosmical

Or so I thought, I wore ten chokers and a chain

Couldn’t see any significance, anger is magical.

Fists to scissors to drugs to pills to fists again

Did you know a poem can be both mythical and archeological?

I ignore the cataphysical, and I anoint my own clavicle.

by Suzi F. Garcia, with some help from Ahmad

from the Academy of American Poets

The institutions tasked with the preservation of art are reducing great works to moralizing message-delivery systems

Alice Gribbin in Tablet:

Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

This vulgar and impoverishing approach to art denigrates the human mind, spirit, and senses. From where did the approach originate, and how did it come to such prominence? Historians a century from now will know better than we do. What can be stated with some certainty is the debasement is nearly complete: The institutions tasked with the promotion and preservation of art have determined that the artwork is a message-delivery system. More important than tracing the origins of this soul-denying formula is to refuse it—to insist on experiences that elevate aesthetics and thereby affirm both life and art.

More here.

Genetic paparazzi are right around the corner, and courts aren’t ready to confront the legal quagmire of DNA theft

Liza Vertinsky and Yaniv Heled in The Conversation:

Every so often stories of genetic theft, or extreme precautions taken to avoid it, make headline news. So it was with a picture of French President Emmanuel Macron and Russian President Vladimir Putin sitting at opposite ends of a very long table after Macron declined to take a Russian PCR COVID-19 test. Many speculated that Macron refused due to security concerns that the Russians would take and use his DNA for nefarious purposes. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz similarly refused to take a Russian PCR COVID-19 test.

Every so often stories of genetic theft, or extreme precautions taken to avoid it, make headline news. So it was with a picture of French President Emmanuel Macron and Russian President Vladimir Putin sitting at opposite ends of a very long table after Macron declined to take a Russian PCR COVID-19 test. Many speculated that Macron refused due to security concerns that the Russians would take and use his DNA for nefarious purposes. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz similarly refused to take a Russian PCR COVID-19 test.

While these concerns may seem relatively new, pop star celebrity Madonna has been raising alarm bells about the potential for nonconsensual, surreptitious collection and testing of DNA for over a decade. She has hired cleaning crews to sterilize her dressing rooms after concerts and requires her own new toilet seats at each stop of her tours.

At first, Madonna was ridiculed for having DNA paranoia. But as more advanced, faster and cheaper genetic technologies have reached the consumer realm, these concerns seem not only reasonable, but justified.

More here.