Guatemala: 1964

..—for Loren Crabtree

The Maya-Quechua Indians plodding to market on feet

…. as flat and tough as toads were semi-starving

but we managed to notice only their brilliant weaving

…. and implacable, picturesque aloofness.

The only people who would talk to us were the village

…. alcoholic, who sold his soul for aguardiente,

and the Bahia nurse, Jenny, middle-aged, English-

…. Nicaraguan, the sole medicine for eighty miles,

who lord knows why befriended us, put us up, even took

…. us in her jeep into the mountains,

where a child, if I remember, needed penicillin, and

…. where the groups of dark, idling men

who since have risen and been crushed noted us with

…. something disconcertingly beyond suspicion.

Good Jenny: it took this long to understand she wasn’t

…. just forgiving us our ferocious innocence.

by. C.K. Williams

from C.K. Williams Selected Poems

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994

Americans love to look on the bright side. We process our traumas and congratulate ourselves on our resilience. We like to crown ourselves winners, avoiding the stigma of the L-word deployed by a certain ex-president. The triumph of the therapeutic, as Philip Rieff called it, even applies to our anti-free-speech college students, who gain vituperative strength from the harm supposedly inflicted on them by other people’s disagreeable opinions.

Americans love to look on the bright side. We process our traumas and congratulate ourselves on our resilience. We like to crown ourselves winners, avoiding the stigma of the L-word deployed by a certain ex-president. The triumph of the therapeutic, as Philip Rieff called it, even applies to our anti-free-speech college students, who gain vituperative strength from the harm supposedly inflicted on them by other people’s disagreeable opinions. Financial literacy — the ability to understand how money works in your life — is considered the secret to taking control of your finances. Knowledge is power, as the saying goes, but information alone doesn’t lead to transformation. In putting financial literacy above all else, many in the personal finance industry have decided that repeating the same facts about how much money folks should have in their emergency savings account will, somehow, change people’s money habits. This approach doesn’t account for our human side: the parts of us that crave connection, new experiences, and fitting in as members of our communities. Most of our decisions around money are emotional; no amount of nitty-gritty knowledge about interest rates will change that.

Financial literacy — the ability to understand how money works in your life — is considered the secret to taking control of your finances. Knowledge is power, as the saying goes, but information alone doesn’t lead to transformation. In putting financial literacy above all else, many in the personal finance industry have decided that repeating the same facts about how much money folks should have in their emergency savings account will, somehow, change people’s money habits. This approach doesn’t account for our human side: the parts of us that crave connection, new experiences, and fitting in as members of our communities. Most of our decisions around money are emotional; no amount of nitty-gritty knowledge about interest rates will change that. Let’s consider where AI poetry is in 2022. Long after Racter’s 1984 debut, there are now scores of websites that use Natural Language Processing to turn words and phrases into poems with a single click of a button. There is even a tool that takes random images and creates haikus around them. You can upload an image of – say, a tree – and the tool will create a simple haiku based around it.

Let’s consider where AI poetry is in 2022. Long after Racter’s 1984 debut, there are now scores of websites that use Natural Language Processing to turn words and phrases into poems with a single click of a button. There is even a tool that takes random images and creates haikus around them. You can upload an image of – say, a tree – and the tool will create a simple haiku based around it. The only way to understand the “public sphere” today is by doing some historical reconstruction. Because what we’re really talking about with the history of literary criticism is an enormous shift between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries away from a media world at the center of which were the genres of periodical publication. The critics who wrote in that media sphere wrote about literature, but they were not professionalized in the way academics in the twentieth century became. This meant that they could write about pretty much anything, and they did. They won their audiences by the quality and force of their writing rather than by virtue of professional credentials. At the same time, these periodicals also published works of literature, serialized novels and other forms of literary writing, so people got a lot of exposure to literature through these periodicals, which had very large audiences. The connection between literature and public-sphere criticism was very close.

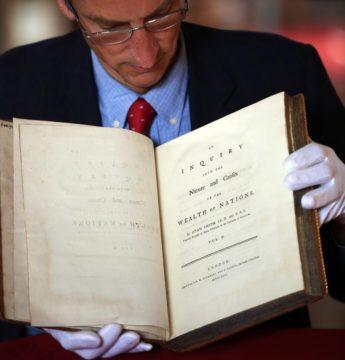

The only way to understand the “public sphere” today is by doing some historical reconstruction. Because what we’re really talking about with the history of literary criticism is an enormous shift between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries away from a media world at the center of which were the genres of periodical publication. The critics who wrote in that media sphere wrote about literature, but they were not professionalized in the way academics in the twentieth century became. This meant that they could write about pretty much anything, and they did. They won their audiences by the quality and force of their writing rather than by virtue of professional credentials. At the same time, these periodicals also published works of literature, serialized novels and other forms of literary writing, so people got a lot of exposure to literature through these periodicals, which had very large audiences. The connection between literature and public-sphere criticism was very close. Thomas O’Dwyer,

Thomas O’Dwyer, A few years ago, my book Small Wrongs was published. It has been

A few years ago, my book Small Wrongs was published. It has been  R

R Fish don’t realize they’re swimming in water.

Fish don’t realize they’re swimming in water. There’s only one word for it: indescribable. “It’s one of those awesome experiences you can’t put into words,” says fish ecologist Simon Thorrold. Thorrold is trying to explain how it feels to dive into the ocean and attach a tag to a whale shark — the most stupendous fish in the sea. “Every single time I do it, I get this huge adrenaline rush,” he says. “That’s partly about the science and the mad race to get the tags fixed. But part of it is just being human and amazed by nature and huge animals.”

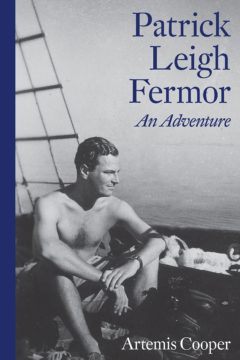

There’s only one word for it: indescribable. “It’s one of those awesome experiences you can’t put into words,” says fish ecologist Simon Thorrold. Thorrold is trying to explain how it feels to dive into the ocean and attach a tag to a whale shark — the most stupendous fish in the sea. “Every single time I do it, I get this huge adrenaline rush,” he says. “That’s partly about the science and the mad race to get the tags fixed. But part of it is just being human and amazed by nature and huge animals.” Rather than repel or frighten him as it might a conventional English gentleman travel-writer, this “atmosphere of entire strangeness” calls to Fermor, pulling him into the fray. Not only does he foray into the local market before even reaching his hotel, but soon afterward he investigates all things Créole—the language, the population, and the dress. Within a mere two days—and despite the fact that Guadeloupe ends up his least inspiring destination—he has so thoroughly immersed himself in the very things whose strangeness had captured his attention that he can bandy Créole patois terms with ease and has decoded the amorous messages indicated by the number of spikes into which the older women tie their silk Madras turbans. What is striking is the thoroughness of his inquiry and his capacity to explain the exotic without eviscerating its alluring quality of otherness.

Rather than repel or frighten him as it might a conventional English gentleman travel-writer, this “atmosphere of entire strangeness” calls to Fermor, pulling him into the fray. Not only does he foray into the local market before even reaching his hotel, but soon afterward he investigates all things Créole—the language, the population, and the dress. Within a mere two days—and despite the fact that Guadeloupe ends up his least inspiring destination—he has so thoroughly immersed himself in the very things whose strangeness had captured his attention that he can bandy Créole patois terms with ease and has decoded the amorous messages indicated by the number of spikes into which the older women tie their silk Madras turbans. What is striking is the thoroughness of his inquiry and his capacity to explain the exotic without eviscerating its alluring quality of otherness. In the spring, just before the launch of Fatherly, a Clemson University student’s

In the spring, just before the launch of Fatherly, a Clemson University student’s  Among the most enigmatic works of his turbulent life, they now occupy a single room at Madrid’s Prado museum, whose collection they entered in 1881. Why Goya painted them, and even if they were all originally painted by the artist himself; how much he revised and changed them, and how much they were further altered by early restorers – all that remains a matter of debate. There is also conjecture about his house (which got its name not from Goya, but from the previous occupant), which was demolished in 1909.

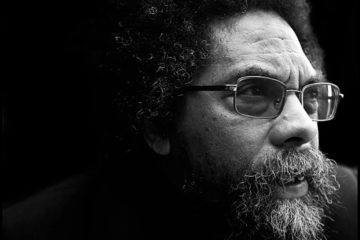

Among the most enigmatic works of his turbulent life, they now occupy a single room at Madrid’s Prado museum, whose collection they entered in 1881. Why Goya painted them, and even if they were all originally painted by the artist himself; how much he revised and changed them, and how much they were further altered by early restorers – all that remains a matter of debate. There is also conjecture about his house (which got its name not from Goya, but from the previous occupant), which was demolished in 1909. Cornel West is one of the most unique philosophical voices in America. He has written a ton of books and taught for over 40 years at schools like Princeton, Harvard, and now at the Union Theological Seminary.

Cornel West is one of the most unique philosophical voices in America. He has written a ton of books and taught for over 40 years at schools like Princeton, Harvard, and now at the Union Theological Seminary.

The horrifying photograph of children fleeing a deadly napalm attack has become a defining image not only of the Vietnam War but the 20th century. Dark smoke billowing behind them, the young subjects’ faces are painted with a mixture of terror, pain and confusion. Soldiers from the South Vietnamese army’s 25th Division follow helplessly behind.

The horrifying photograph of children fleeing a deadly napalm attack has become a defining image not only of the Vietnam War but the 20th century. Dark smoke billowing behind them, the young subjects’ faces are painted with a mixture of terror, pain and confusion. Soldiers from the South Vietnamese army’s 25th Division follow helplessly behind.