Agnes Callard in the New York Times:

What should my friends do if I am being canceled?

What should my friends do if I am being canceled?

A decade ago, when I was a nonpublic philosopher writing only for a small group of academics, it would never have occurred to me to ask myself this question. But things have changed. These days, anyone with a public-facing persona must contemplate the prospect of having her reputation savagely destroyed.

A few years ago, I wrote an essay that, in passing, questioned faculty solidarity with unionizing graduate students. I had not realized how sensitive that topic was, and I was inundated with angry and hateful messages and a few threats online. In the scheme of things, the episode was quite mild, lasting only a few weeks. But it felt all-consuming at the time. And it was a taste of what could come.

More here.

The Republican Party hasn’t adopted a new platform since 2016, so if you want to know what its most influential figures are trying to achieve—what, exactly, they have in mind when they talk about an America finally made great again—you’ll need to look elsewhere for clues. You could listen to Donald Trump, the Party’s de-facto standard-bearer, except that nobody seems to have a handle on what his policy goals are, not even Donald Trump. You could listen to the main aspirants to his throne, such as Governor Ron DeSantis, of Florida, but this would reveal less about what they’re for than about what they’re against: overeducated élites, apart from themselves and their allies; “wokeness,” whatever they’re taking that to mean at the moment; the overzealous wielding of government power, unless their side is doing the wielding. Besides, one person can tell you only so much. A more efficient way to gauge the current mood of the Party is to spend a weekend at the Conservative Political Action Conference, better known as cpac.

The Republican Party hasn’t adopted a new platform since 2016, so if you want to know what its most influential figures are trying to achieve—what, exactly, they have in mind when they talk about an America finally made great again—you’ll need to look elsewhere for clues. You could listen to Donald Trump, the Party’s de-facto standard-bearer, except that nobody seems to have a handle on what his policy goals are, not even Donald Trump. You could listen to the main aspirants to his throne, such as Governor Ron DeSantis, of Florida, but this would reveal less about what they’re for than about what they’re against: overeducated élites, apart from themselves and their allies; “wokeness,” whatever they’re taking that to mean at the moment; the overzealous wielding of government power, unless their side is doing the wielding. Besides, one person can tell you only so much. A more efficient way to gauge the current mood of the Party is to spend a weekend at the Conservative Political Action Conference, better known as cpac. The last known experiment at a Department of Veterans Affairs clinic with psychedelic-assisted therapy started in 1963. That was the year President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. “Surfin’ U.S.A.”

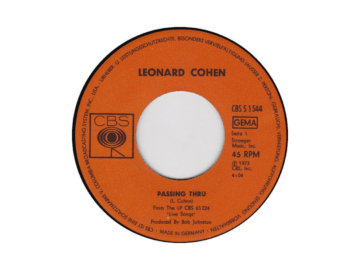

The last known experiment at a Department of Veterans Affairs clinic with psychedelic-assisted therapy started in 1963. That was the year President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. “Surfin’ U.S.A.”  When Leonard Cohen starts singing “Passing Through” on his 1973

When Leonard Cohen starts singing “Passing Through” on his 1973 The Fed’s recipe to bring prices under control will increase the cost of borrowing money, which is good news for creditors, while heavily indebted households that rely on loans for their daily survival will face higher bills.

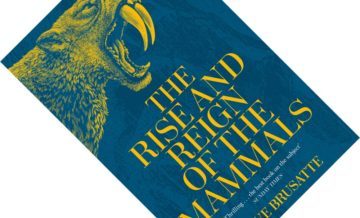

The Fed’s recipe to bring prices under control will increase the cost of borrowing money, which is good news for creditors, while heavily indebted households that rely on loans for their daily survival will face higher bills. Imagine being a successful dinosaur palaeontologist and landing a professorship before you are 40, authoring a leading dinosaur textbook and a New York Times bestseller on dinosaurs. Imagine achieving all that and then saying: “You know what really floats my boat? Mammals.” After the runaway success of his 2018 book

Imagine being a successful dinosaur palaeontologist and landing a professorship before you are 40, authoring a leading dinosaur textbook and a New York Times bestseller on dinosaurs. Imagine achieving all that and then saying: “You know what really floats my boat? Mammals.” After the runaway success of his 2018 book  The past two years have been particularly challenging for the world’s poorest people, and this is just the beginning. By the end of this year, at least 75 million more people will have been pushed into poverty (living on less than US$1.90 a day) than was expected before the pandemic. The war in Ukraine and rising inflation have exacerbated the effects of the pandemic, as prices for food, fuel and nearly everything else have skyrocketed.

The past two years have been particularly challenging for the world’s poorest people, and this is just the beginning. By the end of this year, at least 75 million more people will have been pushed into poverty (living on less than US$1.90 a day) than was expected before the pandemic. The war in Ukraine and rising inflation have exacerbated the effects of the pandemic, as prices for food, fuel and nearly everything else have skyrocketed. Hair ice

Hair ice In a 6-3 majority ruling on Friday, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision giving women the right to abortion. In anticipation of the ruling last week, the Monitor interviewed Geoffrey R. Stone, author of the legal history “Sex and the Constitution.” The history of abortion in the United States is more complicated than many people realize, says Professor Stone, who teaches law at the University of Chicago. Government regulation of abortion has long been connected to the nation’s religious history, caught in the ebbs and flows of evolving cultural mores that also resulted in national prohibitions against contraception, private sexual behavior, and obscenity.

In a 6-3 majority ruling on Friday, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision giving women the right to abortion. In anticipation of the ruling last week, the Monitor interviewed Geoffrey R. Stone, author of the legal history “Sex and the Constitution.” The history of abortion in the United States is more complicated than many people realize, says Professor Stone, who teaches law at the University of Chicago. Government regulation of abortion has long been connected to the nation’s religious history, caught in the ebbs and flows of evolving cultural mores that also resulted in national prohibitions against contraception, private sexual behavior, and obscenity. As the Fourth of July looms with its flags and its barbecues and its full-throated patriotism, I find myself mulling over the idea of American exceptionalism. What, if anything, makes this country different from other countries, or from the rest of the developed world, in terms of morals or ideals? In what ways do our distinct values inform how America treats its own citizens?

As the Fourth of July looms with its flags and its barbecues and its full-throated patriotism, I find myself mulling over the idea of American exceptionalism. What, if anything, makes this country different from other countries, or from the rest of the developed world, in terms of morals or ideals? In what ways do our distinct values inform how America treats its own citizens? Zachary Manfredi in Boston Review:

Zachary Manfredi in Boston Review: