Isaac Chotiner in The New Yorker:

Earlier this year, “The Kashmir Files”—a blood-soaked historical drama with a nearly three-hour run time—became the top-grossing Hindi film since the start of the pandemic. The contested region of Kashmir has caused unending conflict between India and Pakistan. In Indian-administered Kashmir, the Army has brutally subjected Muslims to extensive human-rights violations, with tens of thousands killed, thousands of forced disappearances, and an extremely high incidence of rape—which has been used, according to Human Rights Watch, as a “counterinsurgency tactic” to “create a climate of fear.” But this film tells a different story.

Earlier this year, “The Kashmir Files”—a blood-soaked historical drama with a nearly three-hour run time—became the top-grossing Hindi film since the start of the pandemic. The contested region of Kashmir has caused unending conflict between India and Pakistan. In Indian-administered Kashmir, the Army has brutally subjected Muslims to extensive human-rights violations, with tens of thousands killed, thousands of forced disappearances, and an extremely high incidence of rape—which has been used, according to Human Rights Watch, as a “counterinsurgency tactic” to “create a climate of fear.” But this film tells a different story.

Beginning in 1989, amid an uprising of the state’s Muslim majority following a rigged election, more than a hundred thousand Kashmiri Pandits, a Hindu community, fled from their homes; as many as several hundred were killed. The film, which very clearly frames these killings as a genocide, is cross-cut between the fleeing and terrorized Pandits and a story line in the present day, during which a young Indian man challenges leftist college professors to tell the truth about what happened to his Pandit family.

More here.

When Jennifer Mason posted an ad for a postdoc position in early March, she was eager to have someone on board by April or May to tackle recently funded projects. Instead, it took 2 months to receive a single application. Since then, only two more have come in. “Money is just sitting there that isn’t being used … and there’s these projects that aren’t moving anywhere as a result,” says Mason, an assistant professor in genetics at Clemson University.

When Jennifer Mason posted an ad for a postdoc position in early March, she was eager to have someone on board by April or May to tackle recently funded projects. Instead, it took 2 months to receive a single application. Since then, only two more have come in. “Money is just sitting there that isn’t being used … and there’s these projects that aren’t moving anywhere as a result,” says Mason, an assistant professor in genetics at Clemson University. I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds.

I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds. Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of

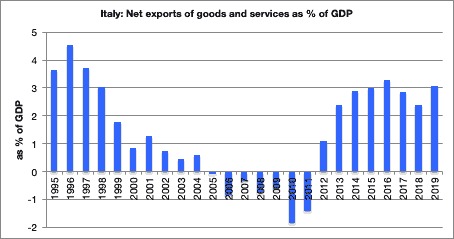

Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of  1. Italy is living below its means

1. Italy is living below its means Dear George Orwell,

Dear George Orwell, A plump larva the length of a paper clip can survive on the material that makes Styrofoam. The organism, commonly called a “superworm,” could transform the way waste managers dispose of one of the most common components in landfills, researchers said, potentially slowing a mounting garbage crisis that is exacerbating climate change. In a paper

A plump larva the length of a paper clip can survive on the material that makes Styrofoam. The organism, commonly called a “superworm,” could transform the way waste managers dispose of one of the most common components in landfills, researchers said, potentially slowing a mounting garbage crisis that is exacerbating climate change. In a paper  PROMINENT WHITE FEMINISTS

PROMINENT WHITE FEMINISTS Jim Al-Khalili has an enviable gig. The Iraqi-British scientist gets to ponder some of the deepest questions—What is time? How do nature’s forces work?—while living the life of a TV and radio personality. Al-Khalili hosts The Life Scientific, a show on BBC Radio 4 featuring his interviews with scientists on the impact of their research and what inspires and motivates them. He’s also presented documentaries and authored popular science books, including a novel, Sun Fall, about the crisis that unfolds when, in 2041, Earth’s magnetic field starts to fail. His latest book, The Joy of Science, is his response to a different crisis.

Jim Al-Khalili has an enviable gig. The Iraqi-British scientist gets to ponder some of the deepest questions—What is time? How do nature’s forces work?—while living the life of a TV and radio personality. Al-Khalili hosts The Life Scientific, a show on BBC Radio 4 featuring his interviews with scientists on the impact of their research and what inspires and motivates them. He’s also presented documentaries and authored popular science books, including a novel, Sun Fall, about the crisis that unfolds when, in 2041, Earth’s magnetic field starts to fail. His latest book, The Joy of Science, is his response to a different crisis. Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World:

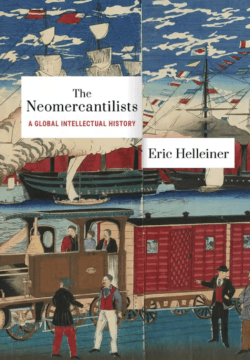

Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World: Nóra Schultz in Tocqueville 21:

Nóra Schultz in Tocqueville 21: Kate Kirkpatrickis and Sonia Kruks in Aeon:

Kate Kirkpatrickis and Sonia Kruks in Aeon: I admit to having been skeptical, ahead of time, of the

I admit to having been skeptical, ahead of time, of the  When the Restoration ended his career in Britain’s Commonwealth government in 1660, John Milton turned his full attention to the verse tragedy he’d started around 1640, then called “Adam Unparadised.” By now in his 50s, blind and ailing, Milton composed “Paradise Lost” aloud, in bed or (per witnesses) “leaning backward obliquely in an easy chair, with his leg flung over the elbow of it,” memorizing the stanzas to be transcribed in another’s hand.

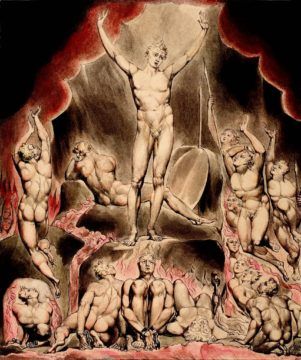

When the Restoration ended his career in Britain’s Commonwealth government in 1660, John Milton turned his full attention to the verse tragedy he’d started around 1640, then called “Adam Unparadised.” By now in his 50s, blind and ailing, Milton composed “Paradise Lost” aloud, in bed or (per witnesses) “leaning backward obliquely in an easy chair, with his leg flung over the elbow of it,” memorizing the stanzas to be transcribed in another’s hand.