Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

All of us construct models of the world, and update them on the basis of evidence brought to us by our senses. Scientists try to be more rigorous about it, but we all do it. It’s natural that this process will depend on what form that sensory input takes. We know that animals, for example, are typically better or worse than humans at sight, hearing, and so on. And as Ed Yong points out in his new book, it goes far beyond that, as many animals use completely different sensory modalities, from echolocation to direct sensing of electric fields. We talk about what those different capabilities might mean for the animal’s-eye (and -ear, etc.) view of the world.

All of us construct models of the world, and update them on the basis of evidence brought to us by our senses. Scientists try to be more rigorous about it, but we all do it. It’s natural that this process will depend on what form that sensory input takes. We know that animals, for example, are typically better or worse than humans at sight, hearing, and so on. And as Ed Yong points out in his new book, it goes far beyond that, as many animals use completely different sensory modalities, from echolocation to direct sensing of electric fields. We talk about what those different capabilities might mean for the animal’s-eye (and -ear, etc.) view of the world.

More here.

Near the end of his brilliant memoir

Near the end of his brilliant memoir  Lidia Yuknavitch’s extraordinary new novel is the weirdest, most mind-blowing book about America I’ve ever inhaled. Part history, part prophecy, all fever dream, “

Lidia Yuknavitch’s extraordinary new novel is the weirdest, most mind-blowing book about America I’ve ever inhaled. Part history, part prophecy, all fever dream, “ Can artificial intelligence come alive?

Can artificial intelligence come alive? Y

Y Microscopic mites that live in human pores and mate on our faces at night are becoming such simplified organisms, due to their unusual lifestyles, that they may soon become one with humans, new research has found.

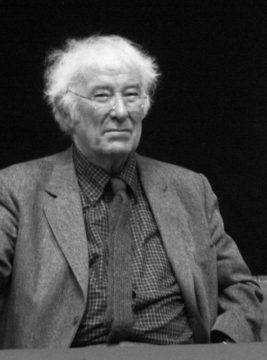

Microscopic mites that live in human pores and mate on our faces at night are becoming such simplified organisms, due to their unusual lifestyles, that they may soon become one with humans, new research has found. When he first began to publish poems, Seamus Heaney’s chosen pseudonym was ‘Incertus’, meaning ‘not sure of himself’. Characteristically, this was a subtle irony. While he referred in later years to a ‘residual Incertus’ inside himself, his early prominence was based on a sure-footed sense of his own direction, an energetic ambition, and his own formidable poetic strengths. It was also based on a respect for his readers which won their trust. ‘Poetry’s special status among the literary arts’, he suggested in a celebrated lecture, ‘derives from the audience’s readiness to . . . credit the poet with a power to open unexpected and unedited communications between our nature and the nature of the reality we inhabit’. Like T. S. Eliot, a constant if oblique presence in his writing life, he prized gaining access to ‘the auditory imagination’ and what it opened up: ‘a feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the levels of conscious thought and feeling, invigorating every word’. His readers felt they shared in this.

When he first began to publish poems, Seamus Heaney’s chosen pseudonym was ‘Incertus’, meaning ‘not sure of himself’. Characteristically, this was a subtle irony. While he referred in later years to a ‘residual Incertus’ inside himself, his early prominence was based on a sure-footed sense of his own direction, an energetic ambition, and his own formidable poetic strengths. It was also based on a respect for his readers which won their trust. ‘Poetry’s special status among the literary arts’, he suggested in a celebrated lecture, ‘derives from the audience’s readiness to . . . credit the poet with a power to open unexpected and unedited communications between our nature and the nature of the reality we inhabit’. Like T. S. Eliot, a constant if oblique presence in his writing life, he prized gaining access to ‘the auditory imagination’ and what it opened up: ‘a feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the levels of conscious thought and feeling, invigorating every word’. His readers felt they shared in this. Nature shows have always prized the dramatic: David Attenborough himself once told me, after filming a series on reptiles and amphibians, frogs “really don’t do very much until they breed, and snakes don’t do very much until they kill.” Such thinking has now become all-consuming, and nature’s dramas have become melodramas. The result is a subtle form of anthropomorphism, in which animals are of interest only if they satisfy familiar human tropes of violence, sex, companionship and perseverance. They’re worth viewing only when we’re secretly viewing a reflection of ourselves.

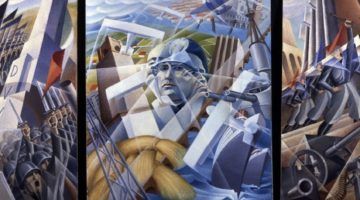

Nature shows have always prized the dramatic: David Attenborough himself once told me, after filming a series on reptiles and amphibians, frogs “really don’t do very much until they breed, and snakes don’t do very much until they kill.” Such thinking has now become all-consuming, and nature’s dramas have become melodramas. The result is a subtle form of anthropomorphism, in which animals are of interest only if they satisfy familiar human tropes of violence, sex, companionship and perseverance. They’re worth viewing only when we’re secretly viewing a reflection of ourselves. “Move fast and break things,” the digital dictum of today’s Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, could have been penned by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his fellow Italian Futurists. Their famous

“Move fast and break things,” the digital dictum of today’s Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, could have been penned by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his fellow Italian Futurists. Their famous  Earlier this year, “The Kashmir Files”—a blood-soaked historical drama with a nearly three-hour run time—became the top-grossing Hindi film since the start of the pandemic. The contested region of Kashmir has caused unending conflict between India and Pakistan. In Indian-administered Kashmir, the Army has brutally subjected Muslims to extensive human-rights violations, with tens of thousands killed, thousands of forced disappearances, and an extremely high incidence of rape—which has been used, according to Human Rights Watch, as a “counterinsurgency tactic” to “create a climate of fear.” But this film tells a different story.

Earlier this year, “The Kashmir Files”—a blood-soaked historical drama with a nearly three-hour run time—became the top-grossing Hindi film since the start of the pandemic. The contested region of Kashmir has caused unending conflict between India and Pakistan. In Indian-administered Kashmir, the Army has brutally subjected Muslims to extensive human-rights violations, with tens of thousands killed, thousands of forced disappearances, and an extremely high incidence of rape—which has been used, according to Human Rights Watch, as a “counterinsurgency tactic” to “create a climate of fear.” But this film tells a different story. When Jennifer Mason posted an ad for a postdoc position in early March, she was eager to have someone on board by April or May to tackle recently funded projects. Instead, it took 2 months to receive a single application. Since then, only two more have come in. “Money is just sitting there that isn’t being used … and there’s these projects that aren’t moving anywhere as a result,” says Mason, an assistant professor in genetics at Clemson University.

When Jennifer Mason posted an ad for a postdoc position in early March, she was eager to have someone on board by April or May to tackle recently funded projects. Instead, it took 2 months to receive a single application. Since then, only two more have come in. “Money is just sitting there that isn’t being used … and there’s these projects that aren’t moving anywhere as a result,” says Mason, an assistant professor in genetics at Clemson University. I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds.

I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds. Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of

Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of  1. Italy is living below its means

1. Italy is living below its means